I remember the first time I really looked at Algol. I’d seen it a hundred times before, just another pinprick of light in the constellation Perseus. But this night was different. I had a chart in my hand and a cheap red flashlight clamped between my teeth. According to the numbers, Algol was supposed to be dim. I looked up, compared it to its neighbors, and sure enough, the “Demon Star” was winking at me. It looked fainter than it had two nights prior.

It gave me goosebumps.

We tend to think of stars as eternal, unchanging rocks in the sky. They aren’t. They are violent, dynamic monsters. Some breathe, some crash into each other, and some tear themselves apart. When you ask, “why does a variable star’s brightness change,” you aren’t asking a simple question. You are pulling on a thread that unravels the physics of the entire universe.

We aren’t talking about a bulb flickering because the wiring is bad. We are talking about nuclear engines the size of a million Earths fighting against gravity. Let’s dig into what is actually happening up there.

More in Celestial Objects Category

Will Our Sun Become a White Dwarf

Why Are Neutron Stars So Dense

Key Takeaways

- It’s Not Always the Star’s Fault: Sometimes the star is stable, but something—like another star or a dust cloud—blocks our view (Extrinsic).

- The Breathing Monsters: Many stars physically expand and contract, changing their temperature and size (Intrinsic/Pulsating).

- The Thieves: Binary stars can steal matter from each other, causing massive explosions on their surfaces (Cataclysmic).

- The Cosmic Speed Limit: We use specific variable stars to measure the size of the universe because their pulsing follows a strict law.

- You Can Help: Professional astronomers rely on amateur backyard observers to track these changes.

What Exactly Is a Light Curve and Why Do We Obsess Over It?

Before we get into the exploding stuff, we need to understand how we track this chaos. You can’t just look at a star once and know it’s variable. You have to stalk it.

Astronomers use something called a light curve. Picture a graph. The bottom axis is time; the vertical axis is brightness. If a star is stable, that line is flat. Boring. But for variable stars, that line goes crazy. It might look like a perfect sine wave, up and down like a heartbeat. Or it might look like a flat line that suddenly drops off a cliff, then climbs back up.

This graph is our Rosetta Stone. The shape of the curve tells us exactly what is happening millions of light-years away. A sharp drop usually means an eclipse. A slow rise and fast fall might mean the star is pulsating. Sudden, erratic spikes? That’s usually an explosion.

When I look at a light curve, I don’t see data points. I see a story. I see a star fighting for its life. But to understand the plot, we have to categorize the actors. Are they changing from the inside, or is something messing with them from the outside?

Wait, Is Something Just Blocking the Light?

Imagine you are watching a lighthouse from miles away. Suddenly, the light dims. Did the bulb die? Probably not. A ship likely passed in front of it.

This happens in space all the time. We call these extrinsic variables. The star itself is perfectly fine. It’s burning fuel, doing its fusion thing, happy as a clam. But from our vantage point on Earth, something gets in the way.

The most common culprits are other stars. Most stars in the Milky Way come in pairs. We call them binary systems. Gravity locks two stars in a dance around a common center. If that orbit lines up perfectly with our line of sight, the stars will pass in front of each other.

This brings us back to Algol, the star that spooked me in my backyard. Algol is an eclipsing binary. Every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, a dim, orange star passes in front of a bright, blue-white star.

The result? The light drops. It’s clockwork. You can set your watch by it. The primary star didn’t change its output; we just lost our view of it for a few hours. It’s a cosmic eclipse.

Could Massive Sunspots Be the Reason?

You know how our Sun has sunspots? Dark, cooler patches caused by magnetic knots? Now, imagine a star where the sunspots are size of vivid hallucinations. We are talking about spots that cover 30% or 40% of the star’s surface.

These are rotating variables. As the star spins, the “dirty” side faces us, and the brightness drops. When the “clean” side spins into view, the brightness spikes.

These stars are usually spinning incredibly fast. That speed generates massive magnetic fields, which create the spots. It’s like a disco ball, but instead of mirrors, it has dark scuff marks. As it spins, the reflection changes.

So, why does a variable star’s brightness change in this case? It’s simply rotation. We are seeing different faces of the same object. It’s a weather report from hell, giving us clues about magnetic storms on a surface we will never visit.

What Drives a Star to Physically Expand and Contract?

Now we get to the really cool stuff: Intrinsic variables. These stars are changing physically. They get bigger, smaller, hotter, and cooler. They are literally breathing.

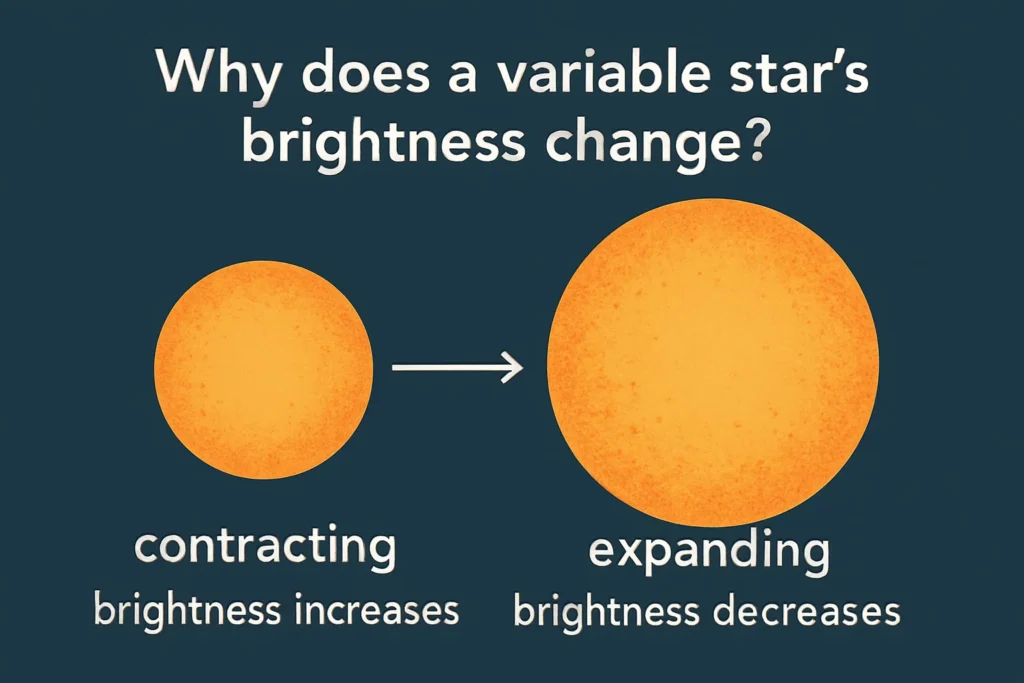

The most famous of these are the Cepheid variables. These stars are giants. They swell up and shrink down in a rhythm that can last days or months. But here is the counter-intuitive part: you’d expect a star to be brightest when it is smallest and hottest, right? Or maybe when it’s biggest?

It’s complicated.

As the star expands, it has more surface area to shine from, which should make it brighter. But expanding gas cools down, which makes it dimmer. The war between size and temperature determines the peak brightness.

But what drives the piston? Why doesn’t the star just settle into a stable size?

How Does the “Eddington Valve” Keep the Heartbeat Going?

Stars are usually in a stalemate. Gravity tries to crush them inward. Nuclear fusion pushes radiation outward. They balance out.

In pulsating stars, this balance breaks. It’s all thanks to a layer of helium deep inside the star. Astronomers call this the “Kappa Mechanism,” but I prefer thinking of it as a steam valve.

Here is the breakdown of the engine:

- Compression: Gravity pulls the star’s outer layers inward. The gas compresses.

- The Trap: As the helium layer compresses, it gets hot—so hot that it loses its electrons (ionization). This makes the helium opaque. It acts like a thick blanket, trapping the heat from the core.

- The Push: The heat can’t escape. Pressure builds up under the blanket. This pressure overcomes gravity and pushes the layers outward. The star inflates.

- The Release: As the star expands, the gas cools. The electrons snap back onto the helium atoms. The gas becomes transparent again.

- The Collapse: The heat escapes into space (this is the brightness we see). The pressure drops. Gravity wins again, and the star falls back inward.

This cycle repeats for millions of years. The star acts like a pot of boiling water with a rattling lid. It captures heat, expands, releases it, and collapses. It’s a perfect, self-regulating engine.

Why Are These Pulsing Stars the “Rulers” of the Universe?

I cannot overstate how important these breathing stars are. In the early 1900s, an astronomer named Henrietta Swan Leavitt noticed something peculiar about Cepheids. She found that the slower they pulsed, the brighter they were in reality (luminosity).

This was a bombshell.

If you measure the timing of the pulse, you know exactly how bright the star should be. Then, you measure how bright it looks from Earth. The difference tells you the distance.

It’s like knowing you have a 100-watt lightbulb. If it looks dim, it’s far away. If it blinds you, it’s close. Before Leavitt’s discovery, we had no reliable way to measure distances to other galaxies. Cepheids are the “standard candles” that let us map the cosmos. Without them, we wouldn’t know the universe is expanding.

Can a Star Explode and Survive?

We often think of explosions as the end. Supernovae destroy stars. But there is a class of variables that explode and live to fight another day. We call them Cataclysmic Variables.

These are the vampires of the stellar world.

Picture a binary system again. But this time, one star is a normal, living sun, and the other is a White Dwarf—a dead, super-dense core of a star roughly the size of Earth. They orbit close. Too close.

The White Dwarf’s gravity is intense. It starts stripping gas off its partner. This hydrogen gas spirals down toward the White Dwarf, forming a flat, glowing disk. Eventually, the gas crashes onto the surface of the dead star.

It piles up. The pressure mounts. The temperature spikes.

Suddenly—FLASH.

The layer of stolen hydrogen undergoes runaway nuclear fusion. It’s a thermonuclear bomb detonating across the entire surface of the star. The system brightens by a factor of thousands in a single day. We call this a Nova.

The explosion blasts the gas layer into space, but the White Dwarf stays intact. It survives the blast. And as soon as the dust clears, it starts feeding again. Some of these stars explode every few decades like clockwork.

What Happens When the “Vampire” Eats Too Much?

There is a dark limit to this feeding frenzy. A White Dwarf can only handle so much mass. This is known as the Chandrasekhar Limit (about 1.4 times the mass of our Sun).

If our vampire star steals enough gas to push it over this weight limit, it doesn’t just have a surface explosion. The core collapses. The carbon and oxygen atoms ignite.

The entire star detonates. This is a Type Ia Supernova.

These are the brightest single events in the universe. For a few weeks, one single dying star can outshine an entire galaxy of billions of stars.

Because they always explode at the exact same mass limit, they always explode with the exact same brightness. This makes them the ultimate “standard candle” for measuring the deepest reaches of the universe. We use them to measure distances across billions of light-years.

Is It Possible for a Star to Just Vanish?

Not every variable star gets brighter. Some play hide and seek.

Take the star R Coronae Borealis. Most of the time, it’s visible to the naked eye or binoculars. Then, without warning, it drops off the map. Its brightness plunges by 99%.

Why? It burped.

These stars are incredibly rich in carbon. Occasionally, the star’s atmosphere becomes unstable and ejects a massive cloud of carbon-rich gas. As this gas moves away from the star, it cools and condenses into soot.

Basically, the star coughs out a gigantic cloud of smoke that blocks its own light. From Earth, we see the star fade away. It stays dim for weeks or months until the radiation pressure (the “wind” of light) blows the soot cloud away.

Astronomers call these “reverse novae.” Instead of a flash of light, you get a sudden disappearance. It’s the most dramatic game of peek-a-boo in nature.

How Do We Actually Catch These Changes?

You might think we have mapped everything by now. We haven’t. The sky is too big.

Professional observatories have huge telescopes, but they have a narrow field of view. They can’t watch the whole sky at once. This creates a massive blind spot.

We rely on surveys—robotic telescopes that scan the sky night after night, looking for anything that moved or changed brightness. When the computer flags a change, it sends out an alert.

But computers aren’t enough. We need eyes on the targets.

- Photometry: This is the science of measuring light. We use digital cameras (CCDs) to count the photons hitting the sensor.

- Spectroscopy: We split the light into a rainbow. This tells us what the star is made of and how fast the gas is moving during a pulse or explosion.

Can You Contribute to Science from Your Backyard?

This is the part I love most. You don’t need a PhD to study variable stars. In fact, the pros need you.

There are too many variable stars for professional astronomers to track. They rely on data from the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO).

This is a global army of amateur astronomers. Some use high-tech backyard observatories; others use simple binoculars. They go out every clear night, estimate the brightness of specific stars, and upload the data.

This data is gold.

If a star like Betelgeuse starts acting weird (like it did in 2019), it’s usually the amateurs who spot it first. They sound the alarm, and then the big telescopes—like Hubble or James Webb—swing into action to see what’s happening.

I’ve submitted observations myself. There is a unique thrill in knowing that the data point you just logged might be used in a research paper five years from now to prove a theory about stellar evolution.

What Does This Tell Us About Our Own Sun?

It’s natural to look at these violent, pulsing, exploding stars and ask: “Is the Sun going to do that?”

Thankfully, no. Or at least, not yet.

Our Sun is a stable, main-sequence star. It doesn’t have a binary companion to steal gas from. It isn’t in the instability strip that causes pulsation. It’s boring. And when you live on a planet, boring is good.

However, studying variable stars acts like a time machine. We can look at young T Tauri stars (wildly variable) to see what the Sun was like 4.5 billion years ago. We can look at Red Giants (pulsating variables) to see what the Sun will become in 5 billion years.

Variable stars show us our past and our future. They remind us that stars have life cycles. They are born in chaos, live in a fragile balance, and die in spectacle.

The Red Giant Mystery: Why Did Betelgeuse Dim?

Speaking of the future, let’s talk about the Great Dimming of 2019. Betelgeuse is the bright red shoulder of Orion. It’s a massive Red Supergiant, destined to go supernova someday.

Suddenly, it started fading. It got dimmer than anyone had seen in recorded history. The internet went wild. “Is it blowing up tonight?” everyone asked.

It didn’t blow up.

After months of analysis, we figured it out. Betelgeuse had likely burped, similar to R Coronae Borealis, but on a smaller scale. It ejected a blob of hot gas. That gas cooled, turned into dust, and blocked the star’s light from our perspective.

This event proved that variable stars can still surprise us. Even the brightest, most well-studied stars in the sky have secrets.

Why Are Red Dwarfs So Angry?

On the other end of the size spectrum, we have Red Dwarfs. These are the most common stars in the galaxy. They are small, cool, and dim. But they are temperamental.

Many of them are Flare Stars.

Because they are so small, the gas inside them churns violently from the core to the surface (convection). This turns the star into a giant magnetic dynamo. The magnetic field lines get twisted and snapped.

When they snap—BOOM.

A flare star can increase its brightness by 100 times in a matter of minutes. It unleashes a torrent of X-rays and UV light. If you lived on a planet around a flare star like Proxima Centauri, your atmosphere might get stripped away by these tantrums.

This changes how we look for alien life. Just because a planet is in the “habitable zone” (the right temperature) doesn’t mean it’s safe. If the star is a variable flare star, life might have a hard time getting started.

The Future of the Changing Sky

We are standing on the edge of a data flood. New telescopes, like the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile, are coming online soon. This beast will scan the entire visible southern sky every few nights.

It’s going to record a movie of the universe.

We expect it to find millions—yes, millions—of new variable stars. We are going to find things that defy our current categories. We might find stars being torn apart by black holes. We might find collisions. We might find patterns in the noise that reveal new physics.

Final Thoughts

Next time you find yourself under a dark sky, don’t just glance up. Stop and really look. Find the constellation Perseus. Find Algol. Watch it.

The universe is not a painting. It’s a machine. It’s grinding, burning, and churning. The light hitting your retina has traveled through the void to tell you a story of gravity and nuclear fire.

Stars are not static. They are alive in the only way a ball of plasma can be. They have a heartbeat. And if you are patient enough, and curious enough, you can watch them breathe. That connection—between your eye and that distant, shifting light—is one of the most profound experiences you can have as a human being.

FAQ – Why Does a Variable Star’s Brightness Change

What is a light curve and why is it important in astronomy?

A light curve is a graph showing a star’s brightness over time; it helps astronomers understand the star’s behavior and categorize its variability, revealing events like eclipses or pulsations.

How do binary stars cause a star’s brightness to vary?

Binary stars can cause brightness variations through eclipses when one star passes in front of the other, temporarily blocking their combined light from our vantage point.

What role do Cepheid variables play in understanding the universe?

Cepheid variables act as standard candles because their pulsation period correlates with their luminosity, allowing astronomers to measure cosmic distances and understand the universe’s expansion.

Can a star explode and still survive?

Yes, some stars like novae or supernovae can explode and survive, especially in the case of novae, where the white dwarf erupts but remains intact, whereas supernovae often result in the star’s destruction.