You walk into a room full of centenarians. Everyone is moving slow, sipping broth, and reminiscing about the 1920s. Then, in the corner, you spot a twenty-something bodybuilder bench-pressing a Buick.

It doesn’t make sense. It shouldn’t be possible.

That’s exactly how astronomers feel when they look at globular clusters. These ancient cities of stars are supposed to be nursing homes for the cosmos. Every star in them formed billions of years ago. The massive, bright blue ones should have exploded or faded ages ago. Only the dim, red, slow-burning stars should be left.

But they aren’t.

Scattered among the cosmic elderly are these bright, hot, blue stars. We call them Blue Stragglers. They shine with a ferocity that defies their age. They mock our models of stellar evolution. The big question that kept scientists up at night for decades is simple: Why do blue stragglers look young when they are actually as old as dirt?

The answer is a little disturbing. It involves cosmic cannibalism, fender benders on a galactic scale, and stars that refuse to die with dignity. Let’s crack open the case files on these stellar cheats.

More in Celestial Objects Category

What Happens If You Fall Into a Black Hole

Key Takeaways

- The Mystery: These stars burn hot and blue in clusters where only old, red stars should exist.

- The Vampire Method: Most stragglers form by sucking hydrogen gas off a neighbor, effectively hitting the “reset” button on their life.

- The Car Crash: In crowded clusters, stars literally smash into each other, merging to form a bigger, hotter star.

- The Hideout: You find them mostly in globular clusters—dense balls of gravity that force stars into uncomfortable proximity.

- The Verdict: They look young because they stole mass. Mass drives stellar youth.

What exactly is a Blue Straggler?

To get why these things are so weird, you have to understand how a star clocks out.

Stars live and die by one rule: Mass is boss.

If you are a fat star (high mass), you burn your fuel like a rock star. You shine blue, live fast, and die young. If you are a skinny star (low mass), you ration your fuel. You burn red and live practically forever.

Globular clusters are the perfect test tube. All the stars in a cluster like 47 Tucanae were born at the same time. It’s a graduation class where everyone is 12 billion years old.

In a group that old, the “rock stars” should be long dead. The party should be over. The only things left should be the low-mass red dwarfs and maybe some yellow stars like our Sun that are getting ready to retire.

But then you look at the chart. Astronomers plot these stars on a Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (think of it as a chart of brightness vs. temperature). You see a nice, orderly line of aging stars, and then—bam. There’s a cluster of rebels.

They sit in the “blue and bright” corner. They act like they just formed yesterday. But there is no gas left in these clusters to make new stars.

How did we miss them for so long?

We didn’t know what we were looking at.

Back in ’53, Allan Sandage was studying the M3 cluster. He expected order. Physics loves order. He expected all the stars to follow the same evolutionary path.

Instead, he found these blue nuisances.

He called them “stragglers” because they looked like they were lagging behind. While the rest of their class had graduated to become Red Giants or White Dwarfs, these stars were still hanging out on the “Main Sequence” (the stellar prime of life).

At first, people thought maybe they were just background stars—photobombers from a younger part of the galaxy. But gravity doesn’t lie. Tracking their movement showed they were locked into the cluster. They belonged there.

That left only one option: Something changed their mass.

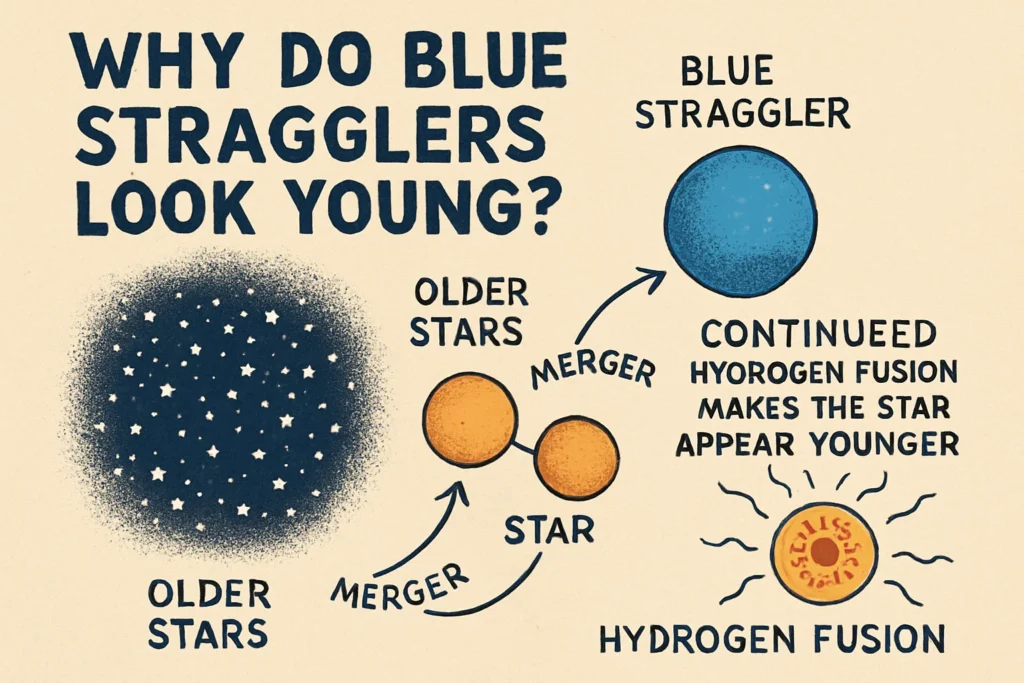

So, why do blue stragglers look young?

Here is the mechanism in plain English.

A star looks “old” when it runs out of hydrogen fuel in its core. It puffs up, turns red, and starts dying.

A star looks “young” as long as it has a full tank of hydrogen to burn.

Blue Stragglers are old stars that managed to refill their gas tanks.

If you take an old, dying star and suddenly dump a massive amount of fresh hydrogen onto it, the weight of that new gas crushes the core. The pressure spikes. The temperature skyrockets. The star turns blue. It starts fusing hydrogen again with the vigor of a teenager.

It’s not magic; it’s just physics. If you add mass, you reset the clock. But stars can’t drive to a gas station. They have to get that gas from a victim.

Is the “Vampire Star” theory real?

Oh, it’s real. And it’s the most common way this happens.

Most stars aren’t lonely singles like our Sun. They live in pairs, orbiting each other. We call them binaries.

Picture a binary couple. Star A is a bit heavier than Star B. Star A ages faster. It runs out of fuel and expands into a Red Giant. It gets huge, bloating out into space.

Star B is sitting right there. As Star A swells up, its outer layers of gas get closer and closer to Star B’s gravity well.

Eventually, Star B starts stripping the gas off Star A. It’s a slow, steady stream of stellar material. Star B drinks the fuel. It gets heavier. It gets hotter. It turns blue.

Star A, the victim, gets stripped down to its naked core and dies as a white dwarf. Star B, the vampire, shines on as a Blue Straggler. It looks young because it’s burning the lifeblood of its partner.

There is distinct evidence for this stellar vampire theory found by Hubble, showing the chemical signatures of this theft.

What about the cosmic car crash?

Sometimes, the universe isn’t subtle. Sometimes it prefers a demolition derby.

In the core of a globular cluster, stars are packed tight. Imagine cramming a million stars into a space only a few dozen light-years across. It’s a mosh pit.

Every now and then, two stars slam into each other.

This isn’t a gentle merger. It’s a violent smash-up. If two low-mass, yellowish stars collide, they don’t just bounce off. They merge. Their combined mass creates a single, much heavier star.

Remember the rule: heavy stars are blue and hot.

So, these two old, dim stars merge to form one bright, blue straggler. It’s a rebirth through violence. The new star spins rapidly from the impact, screaming its presence to the rest of the cluster.

Which method happens more often?

It depends on the neighborhood.

If you are in the suburbs of a cluster—the outer edges where there is plenty of space—you usually get the Vampire method. Collisions are too rare out there. You need a partner to feed on.

If you are in the downtown core, where the stellar traffic is bumper-to-bumper, the Collision method becomes a real player.

Recent surveys suggest the Vampire method (mass transfer) is the dominant creator of these stars overall, simply because binary stars are everywhere. But in the absolute densest environments, the smash-up is king.

Why is the “Turnoff Point” the key clue?

To spot a straggler, you have to look at the “Turnoff Point.”

Think of a candle wick. A thick wick burns fast (blue stars). A thin wick burns slow (red dwarfs).

When you look at a cluster, you can tell its age by seeing who has died. If the blue stars are gone, it’s a bit old. If the yellow stars are dying, it’s very old.

The “Turnoff Point” is that specific spot on the graph where stars are peeling off to die.

Blue Stragglers sit way above this point. They are the guys who stayed at the party after the lights came on. They blatantly violate the age limit of the cluster.

Where do these zombies hang out?

You need a crowded room to find these characters.

You mostly see them in Globular Clusters. Places like M13, Omega Centauri, or 47 Tucanae. These are the oldest structures in the galaxy.

You can find them in Open Clusters (younger groups), but they are harder to spot. If a cluster is already full of young blue stars, a blue straggler just blends in. It’s like wearing a tuxedo to a gala; nobody notices.

But in a Globular Cluster, everyone else is wearing red. The blue straggler wears a neon blue suit. It sticks out.

Why is a globular cluster such a dangerous place?

Gravity is relentless here.

In our part of the galaxy, stars are light-years apart. The chance of the Sun colliding with another star is basically zero.

In a globular cluster, stars pass within a hair’s breadth of each other all the time. This constant gravitational tugging does two things:

- It pushes binary stars closer together, encouraging the Vampire process.

- It steers stars into direct collision courses.

The environment itself breeds these monsters. It forces interactions that peaceful space avoids.

How do we catch them in the act?

We can’t just rely on color. We need to see them spin.

This is the smoking gun.

Old stars are slow. They are like spinning tops that have been going for a week—they wobble and drag. The Sun spins once every 27 days or so.

Blue Stragglers spin like maniacs.

If they formed from a collision, they spin fast because they conserved the orbital energy of the crash.

If they formed from a vampire feeding frenzy, the gas falling onto them spun them up like a finger flicking a globe.

When we point a spectroscope at a blue star in an old cluster and see it rotating 75 times faster than the Sun, we know we’ve got a straggler. No normal old star moves that fast.

Do they cheat death forever?

Nope. You can’t beat thermodynamics.

They bought themselves time. A few billion years, maybe. But eventually, the stolen fuel runs out.

The irony is that because they made themselves more massive, they now burn fuel faster than they did before. They are living the high life, but the bill is coming due.

They will eventually swell up into red giants, just like the partner they cannibalized, and fade into white dwarfs.

Can a star become a straggler all alone?

Not really.

To be a straggler, you need external mass. You need a donor or a collision partner. A single star floating in the void can’t just decide to get heavier. It needs a source.

There are “Field Blue Stragglers” found alone in the galaxy, but they likely started as binaries and got kicked out of their home clusters, or they merged and then drifted away. They carry their history with them.

What is a “Yellow Straggler”?

Just to make things more confusing, they don’t stay blue forever.

As a blue straggler ages (again), it transitions toward the red giant phase. In between, it turns yellow.

These Yellow Stragglers are even harder to spot because they look a lot like normal foreground stars. But they are out there—the middle-aged version of the rejuvenated star. They prove that the cycle of life continues, even for the cheaters.

Why do astronomers obsess over them?

It’s not just because they are cool. They are useful.

Blue Stragglers are the best way to study the history of a cluster.

By counting them, we can figure out the “dynamical age” of a cluster. A cluster with a ton of stragglers in the center has a very dense, active core. A cluster with few stragglers might be more relaxed.

They are also the ultimate lab for studying binary stars. Since binaries make up half the universe, understanding how they interact, merge, and transfer mass is key to understanding everything from supernovae to black hole mergers.

Hubble: The Straggler Hunter

We couldn’t do this without the Hubble Space Telescope.

From the ground, the center of a globular cluster looks like a glowing blob. The atmosphere blurs everything. You can’t count individual stars.

Hubble flies above the blur. It can resolve the pinpoints of light right into the dense core. Hubble gave us the first real census of these stars. It showed us that different clusters have different “straggler populations,” which opened up a whole new field of stellar dynamics.

Could the Sun become one?

Don’t bet on it.

The Sun is a bachelor. No companion star to feed on. And we live in the galactic boonies, far away from the crowded clusters.

The Sun will die a normal, peaceful death. No rejuvenation. No blue phase. Just a slow fade to white.

The messy aftermath: Stellar Shrapnel

Collisions aren’t clean.

When two stars smack into each other, they spray gas everywhere. They can also kick out neighboring stars.

If a collision happens in a triple system (three stars), the two merging stars often fling the third one out of the cluster at breakneck speed. We see these “runaway stars” sprinting through the galaxy. If you trace their path back, it often points right at a globular cluster. They are the witnesses fleeing the crime scene.

The philosophical angle

There is something poetic about these stars.

We like to think of the universe as a clockwork machine. Rules are rules. Stars form, age, and die.

Blue Stragglers break the narrative. They show us that the universe is chaotic, interactive, and messy. They remind us that gravity doesn’t care about “proper” evolution.

Conclusion

Next time you see a photo of a globular cluster—that glittering jewel box of stars—look closely.

It looks peaceful, frozen in time. But now you know better.

Down in the core, it’s a scramble. Stars are dancing, crashing, and stealing. The Blue Stragglers are the survivors of this cosmic brawl. They are the vampires and the brawlers, shining bright blue in a sea of dying red embers, pretending to be young while hiding a dark, violent history.

And honestly? That makes them the most interesting stars in the sky.

FAQ – Why Do Blue Stragglers Look Young

Why do blue straggler stars appear young despite being as old as the globular clusters they inhabit?

Blue straggler stars appear young because they have somehow refilled their hydrogen fuel tanks, either through mass transfer from a companion star or by merging with another star, effectively resetting their stellar aging process.

How do blue stragglers form in globular clusters?

Blue stragglers form mainly through two mechanisms: mass transfer in binary star systems, where a star gains gas from its companion, and stellar collisions, where two stars merge to create a larger, hotter star.

What role does stellar mass play in the life cycle of stars, and why are blue stragglers unusual?

Stellar mass determines a star’s lifespan and brightness; more massive stars burn fuel faster and are brighter but age quickly. Blue stragglers are unusual because they retain a youthful blue appearance despite their old age, which contradicts typical stellar evolution expectations.

Where are blue stragglers typically found, and why?

Blue stragglers are mostly found in globular clusters, dense collections of stars where closer proximity leads to more frequent stellar interactions, such as collisions or mass transfer, which create these younger-looking stars.

Can the Sun become a blue straggler?

No, the Sun cannot become a blue straggler because it does not have a companion star to transfer mass from and is located in a relatively sparse part of the galaxy, making such interactions highly unlikely.