The universe is packed with extremes. It’s got black holes that gobble up light and exploding stars that can outshine their entire galaxy.

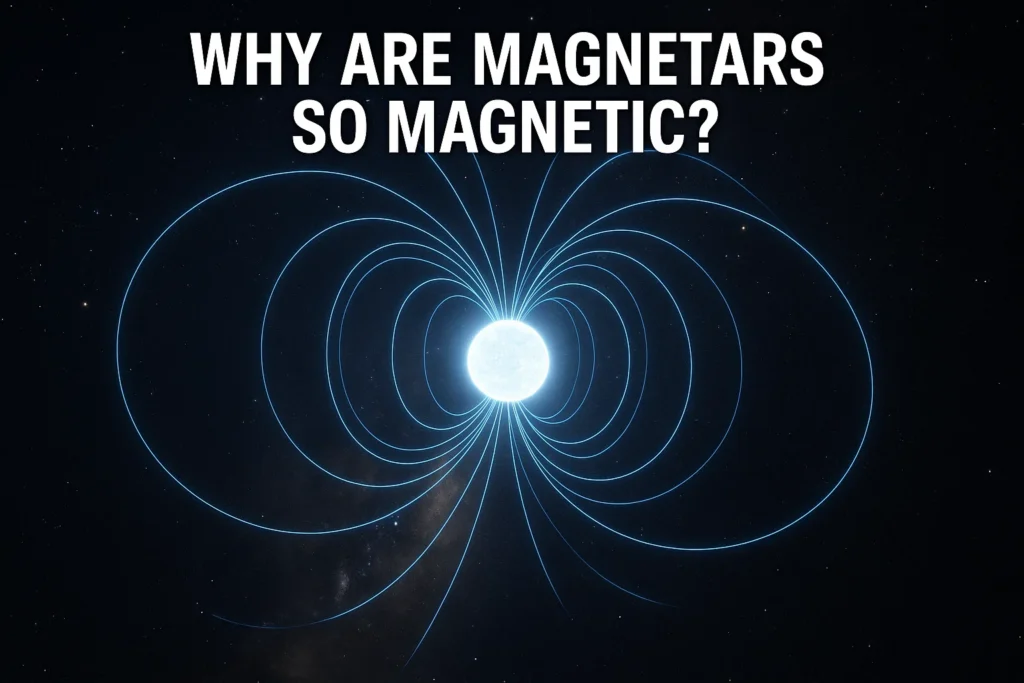

But when you talk about pure, terrifying magnetism, one object leaves everything else in the dust: the magnetar.

These things aren’t just powerful magnets. They are magnetic nightmares. Their power is on a scale that frankly messes with our understanding of physics. They force us to ask some very big questions.

How in the world do they get this way? It’s a question that drills right into the heart of stellar evolution, extreme physics, and the most violent events in the cosmos.

So, why are magnetars so magnetic? The answer, as you might guess, isn’t a simple one. It involves the spectacular death of a giant star, a core spinning at ludicrous speeds, and a violent, short-lived engine called the dynamo effect.

Let’s get into it.

More in Celestial Objects Category

Why Are Neutron Stars So Dense

Key Takeaways

- A Magnetar Is a Souped-Up Neutron Star: It’s the hyper-dense, crushed core of a massive star that died. But its magnetic field is thousands of times stronger than its “normal” neutron star cousins.

- The Power Is Mind-Bending: A magnetar’s field is about one quadrillion (that’s a 1 with 15 zeros) times stronger than Earth’s. It’s so strong it would shred you, atom by atom, from 600 miles away.

- They Aren’t Born This Way: They forge this insane magnetic field in the first few seconds of their existence. The main engine for this is called the dynamo effect.

- The 3-Ingredient Recipe: This dynamo needs three things: a conductive fluid (the hot, soupy core of the brand-new neutron star), convection (a violent, churning motion in that soup), and ridiculously fast rotation (spinning hundreds of times per second).

- It’s Over in a Flash: This entire field-generating process roars to life and dies in about 10 to 20 seconds. After that, the star cools, the churning stops, and the monster field is “frozen” into place.

- This Power Is Also Their Undoing: The field is too strong to be stable. It makes the magnetar’s crust crack, which unleashes the giant gamma-ray flares we see. This instability also means they “die” (lose their magnetic punch) in just 10,000 years or so—a blink of an eye, cosmically speaking.

What Exactly Is a Magnetar, Anyway?

Before we get to the “why,” let’s lock down the “what.”

At its most basic, a magnetar is a specific type of neutron star. And a neutron star is, hands down, one of the weirdest objects in the universe. It’s the “corpse” left over after a truly massive star—one way, way heavier than our sun—explodes in a supernova.

How Does a Star’s Death Create a Neutron Star?

Here’s the play-by-play. A giant star chugs along for millions of years, fusing elements. Eventually, it runs out of fuel in its core. When it does, the delicate balance between gravity trying to crush the star and the fusion energy pushing out is over.

Gravity wins.

The core collapses on itself. This isn’t a slow-motion event; it’s a catastrophic failure in less than a second. The star’s outer layers are blasted into space in that glorious supernova explosion. But the core? It just keeps shrinking.

Gravity gets so absurdly strong that it overcomes the forces that keep atoms apart. It literally jams protons and electrons together to form neutrons. The entire core, which was once thousands of miles wide, gets crushed into a sphere about 12 to 15 miles across.

Think about that. It’s the size of a city.

But here’s the kicker: it contains all the mass of one-and-a-half or even two of our suns.

We are talking about density that makes no intuitive sense. A single teaspoon of this “neutronium” stuff would weigh about 10 million tons on Earth. It’s so dense and its gravity is so strong that the surface is almost perfectly smooth. Any “mountains” would likely be just millimeters high.

This is the object we’re dealing with.

So, What Makes a Magnetar Different?

Okay, if a magnetar is a neutron star, what’s the big deal? Why the special name?

The magnetic field. That’s it.

Most neutron stars are already intensely magnetic. We call them pulsars. Their fields are trillions of times stronger than Earth’s. We thought that was extreme.

But a magnetar is in another league entirely. It’s a neutron star that, because of the specific way it was born, ended up with a magnetic field 1,000 times stronger than a regular pulsar.

That one difference changes everything. It dictates the star’s entire life, its violent behavior, and how we see it. While a pulsar is defined by the lighthouse-like beams of radio waves it shoots from its poles, a magnetar is defined by one thing: pure, untamed, violent magnetic power.

Just How Powerful Is a Magnetar’s Magnetic Field?

We keep throwing around numbers like “quadrillion,” but they’re so big they’re meaningless. Let’s try to put this (10^15 Gauss) field into perspective.

Earth’s magnetic field, the one that guides your compass, is about 0.5 Gauss. A fridge magnet is around 100 Gauss. A big, noisy MRI machine in a hospital, the kind you have to remove all metal to even get near, hits about 30,000 Gauss.

A regular neutron star (a pulsar) has a field of around 10^12 Gauss—a trillion Gauss. A mind-boggling number.

A magnetar clocks in at 10^15 Gauss. One quadrillion.

What Would Happen If I Got Too Close?

Let’s run a little thought experiment. Imagine you’re in a spaceship. You’d die long before you got anywhere near the magnetar. The “kill zone” is enormous.

From 1,000 kilometers (about 600 miles) away, the magnetic field is so powerful it would fundamentally rewrite your body’s chemistry. The magnetic forces would simply overwhelm the electrical bonds that hold your molecules together.

You would be torn apart, atom by atom.

This isn’t the “spaghettification” you’d get from a black hole. This is a diamagnetic distortion of your very atoms. It’s a unique, horrifying way to go.

Even from the distance of our moon, a magnetar would be powerful enough to instantly and completely wipe the data from every single credit card, phone, and hard drive on Earth.

This isn’t just a strong magnet. It’s a force of nature that actively bends the fabric of reality around it.

How Do We Even Know They’re This Magnetic?

It’s a fair question. We obviously can’t send a probe to measure it. So how do astronomers back up these wild claims?

We deduce it from two key pieces of evidence.

First, we measure how fast they slow down. Neutron stars are born spinning incredibly fast. Like a spinning top, they gradually “spin down” as they age. A normal pulsar slows down at a steady, predictable rate.

But a magnetar? It slows down dramatically fast. It’s braking hard.

Why? Because it’s dragging that colossal magnetic field through space. That field acts like a gigantic parachute, bleeding the star’s rotational energy away at a furious and measurable rate. By calculating that braking force, astronomers can work backward to find the field strength required. And the number is… a quadrillion Gauss.

Second, we see the consequences. The field is so strong it’s unstable. It physically twists and stresses the star’s solid crust until, sometimes, the crust breaks.

When the Star’s Crust “Quakes”

This is where magnetars really show off. The twisting, shifting magnetic field puts such immense, unimaginable strain on the star’s solid outer layer that it finally snaps, like the fault line in an earthquake.

We call it a “starquake.”

When the crust cracks, the tangled-up magnetic field lines just beneath the surface suddenly and violently “reconnect.” This process unleashes an amount of energy that is almost impossible to describe. It creates a colossal flare of X-rays and gamma rays.

This is why we also call these objects Soft Gamma-ray Repeaters (SGRs). They “repeat,” sending out burst after burst of high-energy radiation every time their crust cracks.

What Does a Magnetar Flare Look Like?

The most famous—or infamous—event happened on December 27, 2004.

A starquake on a magnetar named SGR 1806-20, located a comfortable 50,000 light-years away on the other side of our galaxy, unleashed a blast of gamma rays.

In one-fifth of a second, it released more energy than our sun has produced in the last 150,000 years.

Let that sink in.

The pulse of radiation was so unbelievably powerful that it slammed into Earth’s atmosphere from 50,000 light-years away. It physically distorted our ionosphere and knocked out satellite communications.

That is the signature of a magnetar. And it’s our biggest clue to its power.

The Big Question: Why Are Magnetars So Magnetic?

This brings us back to the core mystery. You don’t get a quadrillion-Gauss field by accident. It can’t just be the “fossil field” of the original star, all squished down. The numbers just don’t work; the original star would have had to be impossibly magnetic.

No, this field has to be generated. It has to be forged.

The leading, and by far the most accepted, theory for this creation is the convective dynamo effect. It’s an engine that violently turns heat and rotation into magnetism. And it all happens in the first few seconds of the neutron star’s life.

What Is the “Dynamo Effect” in Plain English?

You’re already familiar with a dynamo, even if you don’t know it. Earth has one. It’s the engine in our planet’s core that generates our magnetic field.

A dynamo, in simple terms, needs three ingredients:

- A Conductive Fluid: A material that can conduct electricity, like a liquid. For Earth, this is the molten iron in our outer core.

- Convection: A churning, boiling motion in that fluid. Hot material rises, cool material sinks.

- Rotation: The entire system needs to be spinning.

When you combine these three things, something amazing happens. The spinning, churning, conductive liquid starts to stretch and twist any “seed” magnetic field lines that are present. This motion, thanks to the laws of electromagnetism, creates more magnetic fields. This, in turn, creates even more magnetic fields.

It’s a feedback loop. The faster the spin and the more violent the convection, the stronger the final field becomes.

How Does the Dynamo Work Inside a Newborn Magnetar?

The same three ingredients that work for Earth also show up in a newborn neutron star.

But on a magnetar, they are cranked up to 11.

The “dynamo” that forges a magnetar only exists for a brief, incredibly violent window, right after the supernova’s core collapse. The star isn’t even a “neutron star” yet. It’s what astronomers call a “proto-neutron star.”

Ingredient #1: The “Proto-Neutron Star” Soup

For the first 10 to 20 seconds of its life, the newly-formed neutron star isn’t a stable, solid object. It’s an unbelievably hot (trillions of degrees), dense “soup” of neutrons, protons, and other particles.

And critically, it’s roiling. It’s convective.

This isn’t a gentle simmer. This is a violent, churning cauldron. Hot, neutrino-rich material is boiling up from the center, and cooler material is sinking. This rapidly churning, electrically conductive soup is the perfect “conductive fluid” for our dynamo.

Ingredient #2: Insanely Fast Rotation

This is the most important piece of the puzzle.

When a massive star collapses, it has to conserve its angular momentum.

Think of an ice skater. When she’s spinning with her arms out, she spins slowly. When she pulls her arms in, she spins up, faster and faster.

Now apply that to a star. You have a star’s core, thousands of miles wide, spinning maybe once every few hours. Then, in a flash, it collapses down to an object just 12 miles wide.

All that rotational energy is now packed into a tiny, tiny ball.

The result is a spin rate that is almost impossible to comprehend. A newborn neutron star can spin hundreds of times per second. We’re talking about a rotation period measured in a single millisecond.

Putting It Together: The Convective Dynamo

This is the moment of creation.

You have a hot, violently churning soup (convection). You have that soup spinning at 20% the speed of light (rotation).

This is the most powerful dynamo engine in the universe.

It takes the small “seed” magnetic field from the original star and amplifies it. And it doesn’t just double it. It amplifies it a million, a billion, a trillion times over. This process, known as an alpha-omega dynamo, violently and efficiently converts the star’s immense thermal and rotational energy into magnetic energy.

It’s a runaway process. The faster it spins, the more it churns, and the stronger the field gets, which makes the process even more efficient.

Is This the Only Way to Make a Magnetar?

This dynamo theory is the clear front-runner. It just explains all the evidence so well. But in science, you always have to check the alternatives.

There is another idea, though it has mostly fallen out of favor.

What About the “Fossil Field” Hypothesis?

This is the simpler idea. It suggests that the magnetar’s field isn’t generated at all. It’s just a “fossil” of the original star’s field.

The theory goes like this: what if the parent star that exploded was already hyper-magnetic? A rare, special type of star called a magnetic O-type or B-type star. Then, when the core collapsed, this already-powerful field was simply compressed and “frozen in” to the neutron star, concentrating it to magnetar levels.

Why Isn’t the Fossil Field Theory as Popular?

It’s a “chicken and egg” problem. It doesn’t really answer the question, does it? It just pushes it one step back. Why was the parent star so magnetic?

Furthermore, the numbers are just tough to swallow. The required field strength in the parent star would have to be so high, higher than anything we’ve ever observed. It also doesn’t do a great job of explaining the statistics—why some massive stars produce magnetars and others produce regular pulsars.

The dynamo model is just more satisfying. It explains why rotation is the magic ingredient. It says that any massive star can produce a magnetar, if it’s born spinning fast enough.

What’s the “Window of Opportunity” for This Dynamo?

Here’s the catch. This incredible dynamo engine has an “off” switch.

And it’s on a very short timer.

The “proto-neutron star” phase is incredibly brief. The star is cooling down at a furious rate by blasting out an unimaginable number of particles called neutrinos.

Within about 10 to 20 seconds, the star cools just enough that the violent convection stops. The roiling soup settles down.

When the convection stops, the dynamo shuts off.

This creates a terrifyingly small window of opportunity. The entire process of building a quadrillion-Gauss magnetic field has to happen in the 10-20 seconds before the star “solidifies” and the engine dies.

This leads to a “goldilocks” scenario.

If the newborn star spins too slowly (say, a 10-millisecond period), the dynamo is too weak. It can’t build the field fast enough before the convection stops. The result: a regular, boring pulsar.

But if the star is born spinning just right (a 1-3 millisecond period), the dynamo is a savage beast. It has just enough time to hit that runaway amplification, converting a huge fraction of the star’s rotational energy into a stable, ultra-strong magnetic field.

Then, at 20 seconds, the convection stops. The field “freezes” into the crust.

Boom. A magnetar is born.

What Happens After the Dynamo Shuts Off?

The star is now stuck with a magnetic field it can’t handle.

The field is so strong that it’s no longer just a property of the star; it dominates the star.

This titanic field is now “stuck” in a stable neutron star, but it is not a stable configuration. The magnetic field lines deep inside the star are twisted and tangled up, like a billion rubber bands stretched to the breaking point. This internal field is likely even stronger than the external one we measure.

Why Do Magnetars Die So Young?

All this power comes at a steep price. A magnetar’s life is violent and, cosmically speaking, very short.

That monstrous magnetic field that acts as a brake? It works really well. Magnetars spin down and “die” (stop being so active) in about 10,000 to 100,000 years.

A regular pulsar, by contrast, can spin for 10 million years.

This is why magnetars are so ridiculously rare. Not only are they hard to make (requiring that perfect, high-speed spin at birth), but they don’t live long. We can only see the ones that were born in our very recent cosmic past.

They are the ephemeral monsters of the cosmos, burning incredibly bright and fading away in the blink of a galactic eye.

Why Does Studying These Monsters Even Matter?

This is more than just a cosmic horror story. For physicists, magnetars are an irreplaceable laboratory.

They allow us to test the laws of physics in an environment we can never, ever hope to create on Earth. When a magnetic field gets this strong, it starts to do… weird things.

This is a realm where Einstein’s general relativity (gravity) and quantum electrodynamics (QED, the theory of light and matter) collide. In these fields, light itself can split in two, or merge. The vacuum of space itself is warped and “birefringent,” meaning it acts like a prism.

We are observing physics that, until now, has existed only on a theorist’s blackboard.

Every starquake, every flare, and every tick in their spin-down rate gives us new data on how matter behaves at the absolute edge of existence. Observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope and future X-ray telescopes are designed to peel back these layers, staring into the hearts of these magnetic beasts.

FAQ – Why Are Magnetars So Magnetic

How does a star’s death create a neutron star, and what makes a magnetar different?

When a massive star exhausts its fuel, gravity causes its core to collapse rapidly, crushing protons and electrons into neutrons and forming a neutron star. A magnetar differs from a regular neutron star mainly because it develops an immensely powerful magnetic field—a quadrillion times stronger than Earth’s—due to specific conditions during its formation.

What is the dynamo effect, and how does it produce such an intense magnetic field in a magnetar?

The dynamo effect is a process similar to Earth’s core engine, where a conductive fluid, convection, and rapid rotation generate and amplify magnetic fields. In a magnetar, these conditions are intensified during the first 10 to 20 seconds of its life, rapidly creating a magnetic field trillions of times stronger than Earth’s.

Why do magnetars have such short lifespans compared to other neutron stars?

Magnetars experience extremely powerful magnetic fields that cause them to spin down rapidly and lose their activity in about 10,000 to 100,000 years, a much shorter period than typical pulsars, which can last for millions of years. Their intense magnetic energy makes them unstable and short-lived.

Why are magnetars significant for scientific research?

Magnetars serve as natural laboratories for studying physics under extreme conditions, including intense gravity and magnetic fields, which help scientists understand phenomena such as general relativity and quantum electrodynamics that are impossible to replicate on Earth.