Let’s be honest. Have you ever stepped outside on a supposedly “clear” night, looked up, and felt… nothing?

Total disappointment.

You’ve seen the Hubble pictures. You’ve watched the documentaries. You know, in your head, that the universe is packed with swirling galaxies, glittering star clusters, and entire other worlds. But your sky? It’s just a few lonely pinpricks of light and that weird, hazy peach-colored glow from downtown. It’s a total disconnect. It makes the universe feel fake.

The big question, the one that probably brought you here, is how and where to see celestial bodies for real. Not just on a screen.

Trust me, I get it. I’ve spent more nights than I can count on my own back deck, craning my neck, wondering where the Milky Way went. The truth is, the stars are all still there. We’ve just gotten incredibly good at hiding them from ourselves. But I promise you, with a little planning, you can find them again. You can see things that will genuinely change how you see your spot in the cosmos.

This isn’t a guide for PhDs with million-dollar observatories. This is a guide for you. It’s for anyone with a spark of curiosity who just wants to look up and finally see something.

More in Fundamental Concepts Category

Finding Exoplanets with Radial Velocity

Key Takeaways

- Your Location is 90% of the Battle: You must escape “light pollution.” This is the main barrier between you and where to see celestial bodies. Getting away from city lights is non-negotiable.

- Ditch the Telescope (For Now): Your best tools are your own eyes once they’re dark-adapted. A good pair of binoculars is the only upgrade you’ll need for a long time.

- The Moon is Not Your Friend (Usually): When you look is as critical as where. A bright Moon washes out everything. Plan your adventures around the New Moon.

- Use Modern Tools: Your smartphone is your best friend. Apps can identify everything, find planets, and alert you to cool events like the Space Station passing over.

- Know What to Look For: The night sky isn’t just stars. You can easily find planets, star clusters, and even the Andromeda Galaxy (our closest galactic neighbor) with just a little guidance.

So, Why Does My Backyard Sky Look So Lousy?

It’s a fair question. You pay your taxes, you mow your lawn, and you can’t even get a decent view of the galaxy. What gives? The answer, unfortunately, is simple. We’ve collectively built a luminous bubble around ourselves.

And it’s blocking the view.

Seriously, What’s This ‘Light Pollution’ Thing?

Light pollution is the number one enemy of the stargazer. It’s a catch-all term for all the wasteful, inefficient, and badly-aimed artificial light we spray into the sky.

Think about that streetlight outside your window. It doesn’t just light the street; it sprays light up and sideways, too. Now multiply that by every single streetlight, office building, illuminated billboard, and car headlight in your entire metro area. All that junk light hits dust and moisture in the atmosphere and creates a diffuse, hazy glow. That’s “sky glow.”

What does it do? It washes out the sky. It raises the “floor” of the night’s darkness, making it impossible for our eyes to detect faint objects. A star’s faint, ancient light might travel for a thousand years, only to get snuffed out in the last hundred feet of its journey by the glare from a 24-hour convenience store.

This is why you see maybe 20 stars from the city, but thousands from a dark site.

But is Driving Somewhere Else Really Worth It?

One hundred percent. Yes. It is the whole ballgame.

Astronomers use something called the Bortle Scale to measure sky darkness, with Class 1 being a pristine, untouched sky (almost impossible to find) and Class 9 being an inner-city sky. From a Class 9 or 8 (city or suburban) sky, just forget about the Milky Way. You’ll be lucky to see the main stars of major constellations. The Andromeda Galaxy? Not a chance.

But you don’t have to drive for days. Just moving from a Class 7 (suburban) to a Class 4 (rural) sky is a night-and-day difference. Suddenly, the sky isn’t just black with a few dots; it’s full. It has texture. The Milky Way becomes a visible, glowing band. Faint “fuzzy” objects pop out.

You’re not just looking at stars; you’re looking into a universe. Finding a better spot is step one.

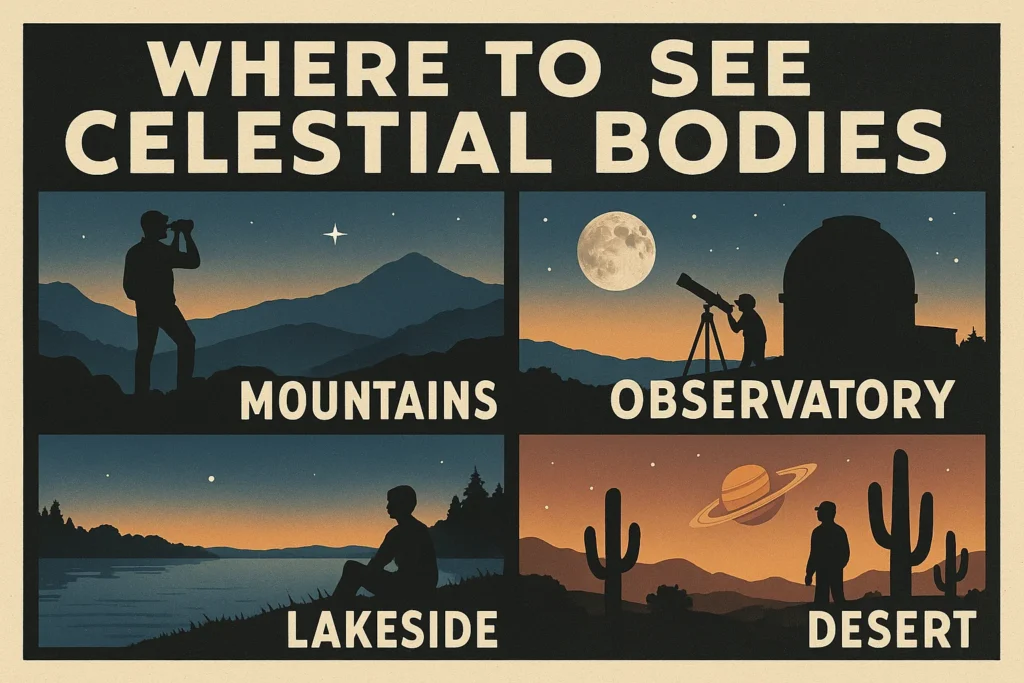

Okay, I’m Sold. Where Do I Go?

Right, so “get out of the city” is the plan. That sounds simple, but where, specifically, should you go? You can’t just pull over on the side of the interstate (please don’t). You need a spot that is both dark and safe.

Luckily, there’s a whole community of nerds (like me) who have already figured this out.

Are There, Like, Official ‘Dark Sky Parks’?

You bet there are. They are your best-case scenario.

An international non-profit organization called the International Dark-Sky Association works tirelessly to protect night environments. They certify locations that meet tough standards for darkness and responsible lighting. These are designated as “International Dark Sky Parks,” “Sanctuaries,” and “Reserves.”

These parks are literal havens for stargazers. They are often state or national parks that have made a specific commitment to cutting their own light pollution and educating the public. Visiting one of these parks on a clear, moonless night is, without exaggeration, a core memory. You will see more stars than you thought possible. You’ll see the Milky Way so clearly it looks like a cloud you could almost touch.

What If I Can’t Drive to the Middle of Nowhere?

Fair enough. Not everyone can just pack up and road-trip to a remote national park for the weekend. The good news is, you just need a darker sky, not necessarily the darkest sky. Your goal is to just put some distance between you and the major metropolitan light domes.

For most people, this is surprisingly achievable. A 45- to 90-minute drive can often be enough to dramatically improve your view.

So, how do you find your local “good enough” spot? Here’s the plan:

- Use a Light Pollution Map: Search online for “light pollution map.” You’ll find several interactive maps that show you, in color-coded detail, where the dark skies are relative to your home. Look for the “green,” “blue,” or “grey” zones. Avoid the red and orange.

- Scout During the Day: Find a promising area on the map, then go check it out in the daytime. You’re looking for a public place, like a state recreation area, a boat launch, or a rural park, that’s open at night. Is there a gate? Does it close at sunset? Find out now, not at 11 PM.

- Look for a Wide-Open View: The ideal spot is on a small hill or in a large, open field, away from trees and buildings that block the view. Trees and buildings are just… in the way.

- Avoid Headlights: The perfect spot is one where you won’t be constantly blinded by car headlights. A quiet county road turnout or a rural cemetery (if you’re not the spooky type) can work. Just be safe, be respectful, and maybe bring a friend.

Don’t I Need a Giant, Expensive Telescope?

This is where people get scared off. They imagine giant, complicated telescopes that cost thousands of dollars.

Let me put your mind at ease. The best stargazing tool you have is the one you were born with.

So, Can I Really See Anything With Just My Eyes?

Absolutely! In fact, you have to start this way. Naked-eye astronomy isn’t just a party trick; it’s the foundation.

From a reasonably dark location, your eyes can pick out thousands of stars. You can trace constellations. You can see the five “naked-eye” planets: Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and sometimes Mercury. On a good night, you can spot the fuzzy patch of the Andromeda Galaxy or the glittering jewel box of the Pleiades star cluster. You can watch “shooting stars” (meteors) streak across the sky.

The most important “gear” here is patience. It takes your pupils about 20 to 30 minutes in total darkness to fully adapt and reach their maximum light-gathering potential.

This means no looking at your phone. Seriously. Put it away. (Unless it has a special red-light filter mode). No car headlights, no flashlights. Just sit in the dark. Be patient. Wait for it. The universe will slowly show up.

What About Binoculars? Are They Any Good?

Good? They’re amazing. This is your first and best upgrade.

If you’re going to spend any money at all, make your first purchase a decent pair of binoculars. I’m serious. A standard 7×50 or 10×50 pair of binoculars is arguably the best all-around astronomy instrument for a beginner. Why? They are intuitive. You already know how to use them. They have a wide field of view, making it easy to find what you’re looking for.

And what they show you is incredible. Those faint fuzzy patches? Binoculars resolve them into stunning objects.

- The Moon: You’ll see mountain ranges and deep craters in stunning 3D relief, especially along the “terminator” (the line between light and dark).

- The Pleiades: What looks like a tiny, misty dipper to the naked eye? It explodes into a glittering cluster of dozens of blue-white stars.

- The Orion Nebula: That fuzzy “star” in Orion’s sword becomes a luminous, ghostly cloud—a place where stars are being born right now.

- The Milky Way: Simply scanning the band of the Milky Way with binoculars is an experience I cannot overstate. It’s not a “cloud”; it’s a river of millions of individual stars. It’s unreal.

So, When Do I Get the Telescope?

Later. Maybe.

And I say that as a guy who loves his telescopes. But here’s the hard truth: telescopes are frustrating for beginners. They have a tiny field of view, which makes finding things incredibly difficult. They often show you an image that’s upside-down and backward. A cheap, wobbly telescope will show you less than your binoculars and will just end up in the garage.

My advice? Start with your eyes. Graduate to binoculars. Spend a full year learning the constellations, tracking the planets, and truly getting to know the sky. Once you’ve done that, if you find yourself saying, “I really want to see the rings of Saturn” or “I wish I could get a closer look at Jupiter’s moons,” then you’re ready to research a good beginner telescope.

But don’t rush it. The fun is in the learning.

What Am I Even Looking At Up There?

Okay, you’ve found a dark spot. You’ve let your eyes adapt. You’re looking up at a dizzying number of stars. Now what?

It’s time to put some names to the faces. Learning to identify a few key objects is what turns stargazing from a passive “wow” moment into an active, engaging hobby.

How Can I Tell a Planet from a Star (Without a Degree)?

This is the classic beginner question. Thankfully, there’s a simple test:

Stars twinkle. Planets don’t (mostly).

Why? It’s all about the atmosphere. Stars are so incredibly far away that they are, for all practical purposes, a single point of light. As that tiny point of light enters our turbulent atmosphere, it gets bounced around, bent, and refracted. That’s “twinkling.”

Planets, on the other hand, are way closer. Even though they look like dots, they are actual disks. Their light comes from a larger (apparent) area, so it’s less affected by the turbulence. It shines with a steadier, more solid glow.

The other clue is location. The planets in our solar system, plus the Sun and Moon, all follow the same general “highway” across the sky (called the ecliptic). If you see a bright “star” that doesn’t twinkle and it’s on this path, you’ve found a planet.

What About All Those Faint, Fuzzy Smudges?

This is where the real magic starts. The sky is full of objects that aren’t single stars. These are the deep-sky objects, and they are the true treasures for those who seek out.

- The Moon: Don’t discount it! The Moon is our closest companion and it’s spectacular. The best time to observe it is not when it’s full. A full moon is so bright it washes out its own detail (and the rest of the sky). Look for it during its quarter or crescent phases. The shadows cast along the terminator reveal craters and mountains in magnificent detail.

- Planets: You can see five with the naked eye. Venus is the brightest, always found near the Sun just after sunset or before sunrise. Jupiter is also a king, a steady, brilliant light. With good binoculars, you can often see its four largest “Galilean” moons as tiny pinpricks lined up beside it. Mars is distinctly reddish. Saturn is a calmer, yellowish light. You’ll need a telescope to see its rings, but it’s still a joy to find.

- The Milky Way: This is our home. The hazy, glowing band you see stretching across the sky is the disk of our own galaxy, viewed from the inside. The “fuzz” is the combined light of billions of stars too far away to see individually.

- Galaxies and Nebulae: The most famous “fuzzy patch” is M31, the Andromeda Galaxy. Over 2.5 million light-years away, it’s the most distant object the human eye can see. From a dark sky, it looks like a small, faint, oval-shaped smudge. But when you realize that smudge is a “sister city” of stars, a galaxy even larger than our own, it’s humbling. Closer to home is the Orion Nebula (M42), a vast cloud of gas and dust in the “sword” of the constellation Orion. It’s a stellar nursery, a place where new stars are actively being born.

How Do I Know When and Where to Look?

This is the final piece of the puzzle. You’re in a dark place, you have your binoculars, but the sky is… big. How do you find anything?

You need a map. And you need a calendar.

Is There an App for This? (Please Say Yes)

Yes, and they are total game-changers.

Twenty years ago, you’d need a star chart, a planisphere (one of those cardboard spinning things), and a red flashlight. Today, you just need your phone. Stargazing apps are, without question, the most powerful tool a beginner has.

Apps like SkyView, Stellarium, Star Walk, or Night Sky use your phone’s built-in compass, GPS, and gyroscope. You just download one (many are free), point your phone at the sky, and it will tell you exactly what you’re looking at.

Point it at a bright “star”? The app says, “That’s Jupiter.” Wondering what that constellation is? The app will trace it out and tell you it’s Cassiopeia. You can search for “Mars,” and an arrow will appear, guiding you to it. These apps remove all the guesswork and frustration, letting you build confidence and learn the sky at your own pace.

When’s the Best ‘Time’ to Go?

There are two “times” to consider: the time of the month and the time of the year.

The most important is the phase of the Moon. The Moon is beautiful, but it’s also a giant spotlight. A full moon is so bright it creates its own light pollution, washing out the Milky Way and all but the brightest stars. For seeing faint stuff, the best time is the week around the New Moon. This is when the Moon is dark, leaving the sky to the stars.

The time of year dictates which constellations you’ll see. The Earth is on a journey around the Sun, so the “night” side of our planet is constantly pointing at a different part of the universe. The brilliant constellations of winter (like Orion, Taurus, and Gemini) are replaced by the summer constellations (like Sagittarius, Cygnus, and Lyra). This is why the “Milky Way season” for the Northern Hemisphere is in the summer—that’s when we’re facing the galaxy’s bright, dense core.

What About Those “Shooting Stars”?

“Shooting stars” are not stars at all. They are meteors—tiny bits of dust and debris (often no bigger than a grain of sand) left behind by comets. When the Earth plows through one of these debris trails in its orbit, the particles burn up in our atmosphere at incredible speeds, creating those brief, beautiful streaks of light.

These “meteor showers” are predictable. We know when the Earth will cross these trails every year. While you can see a random meteor on any given night, your chances go way, way up during a shower’s “peak.”

Some of the best annual meteor showers include:

- The Perseids: Peaking around August 12-13. This is the most famous summer shower, known for its bright, fast meteors.

- The Geminids: Peaking around December 13-14. This is perhaps the most reliable and active shower of the year, with slow-moving, bright meteors.

- The Orionids: Peaking around October 21-22. This shower comes from the debris of the famous Halley’s Comet.

The best way to watch is the simplest. Go to a dark spot, lie back on a blanket or in a lounge chair, look straight up, and be patient. No telescope, no binoculars. Just watch the sky.

Give Me a ‘Must-See’ List to Start

You’re all set. You’ve got a dark sky, a moonless night, and a pair of binoculars. Here is your starter checklist—the sights that truly bridge the gap between Earth and the cosmos.

Go find these.

How Do I Finally See the Milky Way?

I’ve mentioned it a lot, but it deserves its own section. Seeing the Milky Way for the first time is the quintessential stargazing experience.

To do it, you need a dark sky (Bortle Class 4 or better) and a moonless night. In the Northern Hemisphere, the best views are during the summer, from roughly June through September. This is when the bright, bulging central core of our galaxy is high in the southern sky. Look for the constellation Sagittarius—it looks like a “teapot.” The Milky Way appears as a cloud of “steam” rising from the teapot’s spout. This “steam” is the galactic center, a region of unimaginable density and home to a supermassive black hole.

Scanning this area with binoculars is, quite simply, mind-blowing.

How Can I Spot the Space Station?

This one is just plain cool. You’ll be looking at a 100-billion-dollar football-field-sized laboratory, orbiting the Earth at 17,000 miles per hour, with astronauts living and working inside. And you can see it from your backyard.

The ISS looks like an intensely bright star—often the brightest object in the sky—moving fast and steadily and silently across the night. It doesn’t blink or twinkle. Because it’s in orbit, it’s only visible when it’s in sunlight and your location is in darkness (usually just after dusk or before dawn).

The passes are predictable down to the second. Use NASA’s “Spot the Station” website or an app like “ISS Detector.” They will tell you exactly when and where to look. It’s a 5-minute event that never gets old.

What About Eclipses or Other Big ‘Events’?

Eclipses are the Super Bowl of stargazing. They are line-of-sight alignments of the Sun, Moon, and Earth.

A lunar eclipse—when the full moon passes through Earth’s shadow—is a beautiful, slow-motion event visible to anyone on the night side of the Earth. A total solar eclipse, when the New Moon perfectly blocks the Sun, is something else entirely. It is, by all accounts, the most spectacular, terrifying, and profound natural event a human can witness. It turns day into a weird, 360-degree twilight, and the Sun’s fiery atmosphere (the corona) becomes visible to the naked eye.

They are rare and happen only along a very narrow path. If one ever happens near you, go. Don’t make excuses. Just go.

Beyond eclipses, keep an eye out for “conjunctions.” This is when two or more planets appear very close together in the sky. They have no physical meaning, but they are beautiful, serene alignments to watch.

It’s Your Sky. Go Look at It.

The night sky is a book, written in the language of light. From the city, we can only read the cover. But just a short drive away, the pages open up. You learn that the universe isn’t a static, black-and-white photo; it’s a dynamic, three-dimensional, and colorful place.

Finding where to see celestial bodies isn’t just a physical trip to a darker location; it’s a personal one. It’s about slowing down, unplugging from the artificial glare, and letting your eyes adjust to an older, deeper reality. It’s about finding your bearings, not by a street sign, but by a star that has guided travelers for millennia. It’s about that jolt of connection when you spot the ISS and wave (we all do it).

You don’t need to be a scientist to do this. You just need to be curious. You just need to know where to look.

So, check the lunar calendar. Find a dark spot on a map. Grab a blanket, a pair of binoculars, and maybe a thermos of coffee.

Go look up.

FAQ – Where to See Celestial Bodies

Why is it important to escape light pollution to see celestial bodies clearly?

Escaping light pollution is crucial because artificial lights from urban areas create a diffuse glow in the sky, washing out faint celestial objects and making it difficult or impossible to see stars, galaxies, and other deep-sky objects clearly.

Can I observe stars and planets with just my eyes?

Yes, your naked eyes are capable of seeing thousands of stars, the five planets visible to the naked eye, and objects like the Milky Way, especially when you are in a dark, rural location away from city lights.

What are the best tools for beginner stargazing?

The best tools for beginners are your own eyes once dark-adapted, along with a good pair of binoculars, such as 7×50 or 10×50, which are excellent for exploring the sky and viewing faint objects more clearly.

When is the optimal time to go stargazing in relation to the Moon?

The optimal time for stargazing is during a New Moon, when the Moon is not visible and its brightness does not interfere with seeing faint stars, nebulae, and other deep-sky objects.

How can I identify celestial objects like stars, planets, or the Milky Way when I look up at the sky?

You can identify celestial objects using stargazing apps on your smartphone, which utilize GPS and compass features to point out stars, planets, constellations, and other objects, making it easier to learn the night sky and know what you are seeing.