When you picture a comet, what do you see? Probably that classic, stunning image: a bright, fuzzy smudge of a head, with a brilliant, glowing tail streaming out behind it, slicing across the blackness of space. It’s an awesome sight. For thousands of years, people saw these “hairy stars” and wondered. What were they? Omens? Messengers? We know now they’re ancient chunks of ice and rock from the solar system’s edge. But that one big question still gets asked all the time: what causes a comet’s tail?

The answer is simpler than you might think. It’s our star. The Sun.

That incredible tail isn’t just along for the ride. It’s the visible, real-time story of that comet getting blasted by the Sun’s awesome power. It’s a tale of ice turning straight to gas, of a relentless solar wind, and of the quiet, steady push of sunlight itself.

More in Fundamental Concepts Category

Why Are Meteors Called Shooting Stars

Key Takeaways

So before we get into the nitty-gritty, here’s the fast-and-simple version of what’s going on.

- Comets are basically “dirty snowballs.” Think of them as massive balls of ice (water, dry ice, etc.), rock, and dust, all frozen together. They’re leftovers from when the solar system first formed.

- The Sun’s heat kicks things off. When a comet’s orbit brings it close to the Sun, the heat is intense. It causes the ice to skip being liquid and turn straight into a gas (that’s called sublimation), which makes a big, fuzzy cloud called a “coma.”

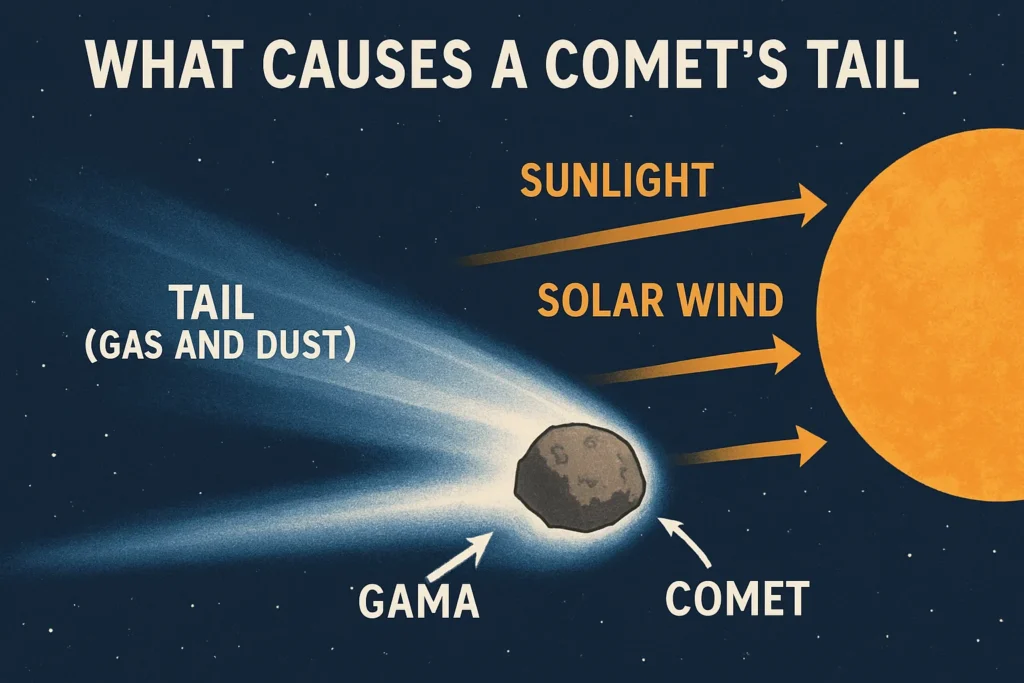

- A comet actually has two tails. That’s right, not one. The Sun’s power creates two different tails: a thin, blue, and straight ion tail (made of gas) and a broad, white, and curved dust tail.

- Two different solar forces are at work. The solar wind (a fast stream of particles from the Sun) creates the ion tail. The push of sunlight itself (radiation pressure) creates the dust tail.

- Tails always point away from the Sun. Since both the solar wind and sunlight are pushing out from the Sun, the tails always stream away from it, no matter which direction the comet is flying.

So, What Exactly Is a Comet?

Okay, before we get to the tail, let’s talk about the comet itself. What is this thing?

At its heart, a comet is pretty simple. You’ll hear astronomers call them “dirty snowballs,” and honestly, that’s the perfect way to think about them. They are basically cosmic fossils—leftover junk from the birth of our solar system, way back 4.6 billion years ago.

Picture a giant, lumpy potato, maybe a few miles wide. That’s the “nucleus,” the solid part of the comet. It’s a frozen mix of different ices. Sure, there’s a ton of regular water ice. But it’s also packed with frozen gases like carbon dioxide (you know it as dry ice), methane, ammonia, and carbon monoxide.

This isn’t a clean snowball, though. Mixed in with all that ice is a huge amount of dust, sand, and rock. That “dirt” is what makes the nucleus super dark and sooty-looking, and it’s what earns it the “dirty snowball” name.

Where Do These Cosmic Snowballs Live?

For most of their long lives, comets are just… boring. They live out in the deep freeze of the outer solar system, way beyond the planets. Out there, they’re just dark, frozen lumps, completely invisible to us.

Most of them hang out in two main places:

- The Kuiper Belt: This is a huge ring of icy objects just past Neptune’s orbit. You can think of it as a sort of “comet suburb” for the solar system.

- The Oort Cloud: This is a massive, spherical shell of icy stuff that surrounds our entire solar system. It’s thousands of times farther away than Pluto. This is the “deep country,” the comets’ homeland.

A comet can spend billions of years in that cold darkness. Then, something changes. A tiny gravitational nudge from a passing star or a jostle from another object can change its path. Suddenly, it’s on a new, long, looping orbit that’s going to send it plunging down toward the warm, bright, inner solar system.

Plunging it toward the Sun.

Why Is a Comet “Dirty”?

That “dirt” is a huge part of the story, not just a detail. This mix of rock particles and dark, carbon-based dust is all mixed up with the ices.

This material is pristine. It’s unchanged. It hasn’t been cooked or melted in over four billion years. When that dust and rock finally gets released from the ice, it gives us clues about the exact recipe that built our solar system—the planets, the moons, and maybe even us.

This dirty, icy nucleus is the source of everything that’s about to happen. It’s the “engine” of the comet. And as it falls toward the Sun, the show is about to start.

The Sun’s Heat: The Great Unveiling?

Out in the deep, a comet is just a nucleus. No coma. No tail. Just a dark chunk of ice and rock. But as that orbit brings it closer and closer—say, past the orbit of Jupiter—things start to change. Fast.

The Sun’s energy, its heat and light, starts to hammer the nucleus. This is where the magic happens. The ice on the surface doesn’t get a chance to melt. In the vacuum of space, it does something much more violent: sublimation.

What Is Sublimation, Anyway?

Sublimation is just a word for a solid turning directly into a gas, completely skipping the liquid phase.

You’ve seen this on Earth with dry ice. If you leave a block of it out, it doesn’t melt into a puddle. It just “smokes,” turning right into carbon dioxide gas.

The exact same thing happens on the comet. The Sun’s heat hits the nucleus, and the frozen ices—water, carbon dioxide, all of it—erupt violently from the surface. They blast off as a gas, carrying all that “dirt” with them. This is the moment the comet wakes up.

What Is This “Coma” I Keep Hearing About?

This massive, expanding cloud of gas and dust that blows off the nucleus is called the coma. It’s basically the comet’s temporary atmosphere. And it can get enormous.

The solid nucleus might only be a few miles across. But the coma? It can swell to be tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of miles wide. It can easily become bigger than the planet Jupiter.

All of a sudden, that tiny, dark rock is hidden inside a giant, fuzzy, glowing ball. The Sun’s light shines off all the dust particles, and its ultraviolet radiation makes the gases glow. The comet, once invisible, is now a brilliant object.

But the Sun isn’t done. Its heat made the coma. Now, its other forces are going to grab that coma and stretch it into a tail.

Now for the Main Event: What Causes a Comet’s Tail?

This is the big moment. The nucleus is erupting. The coma is huge and bright. The comet is now close enough for the Sun to unleash its other major weapons. The thing is, the “tail” isn’t just one thing. It’s a mistake to think of it as “the tail.”

A comet actually has two main tails.

They are formed by two totally different forces from the Sun. They’re made of different materials. And they point in slightly different directions.

This is the beautiful, complex answer to “what causes a comet’s tail.” It’s a one-two punch from our star. The first punch comes from the Sun’s solar wind. The second punch comes from the Sun’s radiation pressure.

Is It Just One Tail, or Am I Seeing Double?

You’re not seeing double. In a lot of clear photos of comets, you can really see both of them.

- The Ion Tail (or Plasma Tail): This one is usually thinner, straighter, and glows with a distinct blue light. It’s made of gas.

- The Dust Tail: This one is typically broader, more spread out, and has a yellowish-white color. It’s made of, you guessed it, dust.

Understanding these two tails is the key to understanding the whole show. Let’s tackle them one by one.

The Ion Tail: What’s That Blue Streak?

The ion tail is the more dramatic of the two. It’s a direct, high-speed “wind sock” that shows us what the Sun is doing. It’s made up entirely of gas.

Here’s the play-by-play. The gas that first erupts from the comet’s nucleus (water, carbon monoxide, etc.) is electrically neutral. But it doesn’t get to stay that way for long.

How Does the Sun Create This Blue Tail?

The Sun doesn’t just pump out heat and light. It’s also blasting the solar system with intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This high-energy UV light smashes into the gas molecules in the coma. It’s so powerful that it physically knocks electrons off the gas molecules.

When an atom or molecule loses an electron, it’s not neutral anymore. It now has a positive charge. It has become an “ion.”

This process is called ionization. The coma is now full of this cloud of charged gas, or “plasma.”

What Is the Solar Wind’s Role in This?

Now we bring in the Sun’s other force: the solar wind. This isn’t wind like we have on Earth. It’s a constant, supersonic stream of charged particles (mostly protons and electrons) that the Sun blasts out in all directions, traveling at a million miles per hour or more.

This solar wind carries its own magnetic field. When this high-speed, magnetic wind slams into the cloud of ions in the coma, it grabs them. It “picks them up” and throws them backward.

The ion tail is simply the solar wind blowing those glowing ions straight back, away from the Sun. This is why the ion tail is always a perfectly straight line, pointing directly away from the Sun, no matter which way the comet itself is moving.

And that cool blue glow? That’s fluorescence. The ions, especially carbon monoxide, get energized by the Sun’s radiation and glow, just like a neon sign.

The Dust Tail: Why Is It White and Curved?

So, the super-fast solar wind takes care of the gas. But what about all the “dirt”? What about the trillions of tiny dust particles and gritty bits that were frozen in the ice?

The solar wind is a stream of tiny particles. It doesn’t have enough muscle to move these much heavier, solid dust grains. They need a different kind of push. And the Sun provides it.

This force is called solar radiation pressure.

How Does Sunlight Push Dust?

It sounds like science fiction, but it’s totally real. Sunlight itself can push things.

Light is made of particles called photons. Photons don’t have mass, but they have momentum. When a photon hits a tiny, reflective dust particle, it bounces off and transfers a tiny bit of that momentum. It gives the particle a tiny, tiny push.

One photon’s push is almost nothing. But a comet is near the Sun. It’s being hit by an unimaginable number of photons every single second.

For a big object like a planet, this push is nothing. But for a microscopic particle of dust floating in the coma, that tiny, relentless push from quadrillions of photons adds up. It’s enough to slowly, but surely, push the dust particle away from the Sun.

Why Does the Dust Tail Curve?

This is the key difference. The ion tail is formed by the super-fast solar wind blasting lightweight ions straight back. The dust tail is formed by the much weaker push of sunlight on heavier dust particles.

Because the push is so gentle, the dust particles get pushed away from the Sun much more slowly.

But here’s the trick: the comet itself is still moving. It’s still flying along its orbit.

So, you have these dust particles being pushed slowly away from the Sun, but they are also trying to follow along with the comet in its original orbit. Think of it like a person on a moving speedboat (the comet) dropping heavy weights (the dust) into the water. The weights will trail behind the boat in a gentle curve.

The dust particles “lag behind” the comet in its orbit. This creates that broad, diffuse, and noticeably curved tail. And its color? It’s not glowing blue like the ions. It’s just a simple, yellowish-white. We’re just seeing sunlight reflecting off the dust, plain and simple.

So, the Tails Point in Different Directions?

That’s right! It’s one of the coolest parts. You get this beautiful, two-pronged display.

- The blue ion tail acts like a weather vane. It’s a straight line that shows you exactly which way the solar wind is blowing (directly away from the Sun).

- The white dust tail acts like a trail of breadcrumbs. It’s a curved path that shows you where the comet has been in its orbit.

The angle between these two tails can change as the comet moves, giving each comet a unique and dynamic look.

How Big Can These Tails Get?

When we see pictures, it’s hard to get a sense of scale. Are we talking about tails the size of a city? A country?

Try the size of a planet. Or much, much bigger.

The tails of comets are, without exaggeration, some of the largest structures in our entire solar system. The coma alone can be bigger than Jupiter. The tails, though? They can be staggering.

A typical comet’s tail is millions of miles long. It’s totally normal for a tail to stretch for 10 million or 50 million miles.

Are We Talking “Long” or “Astronomically Long”?

We are talking astronomically long.

To give you some perspective, the distance from the Earth to the Sun is about 93 million miles. We call this 1 Astronomical Unit (AU).

The Great Comet of 1843 had a tail that stretched over 2 AU. That’s more than 186 million miles (300 million kilometers) long. Its tail was longer than the entire distance from the Sun out to Mars.

In 2007, Comet McNaught, which put on an incredible show for the Southern Hemisphere, had a tail so enormous and complex that you could briefly see it in broad daylight.

Our own planet has even flown through a comet’s tail. In 1910, Earth passed right through the tail of Halley’s Comet. People panicked a bit, but the tail material is so incredibly thin—it’s a better vacuum than anything we can make in a lab—that it had zero effect on us.

Does a Comet Have a Tail Forever?

A comet’s tail is a sign of its glory. It’s also a sign of its death.

That beautiful display is the comet actively dissolving. It’s bleeding its own body out into space. A comet is not a permanent object. It has a life cycle: it’s born in the cold, it lives a quiet life, and then it has a spectacular, fiery end.

Every single time a comet swings in close to the Sun, the “faucet” turns on. Jets of gas and dust erupt from the nucleus, getting blown away to form the coma and tails.

This is material that is lost forever.

What Happens to a Comet After Many Trips?

With every pass, the comet loses another layer of ice. Scientists estimate that a comet like Halley’s, which comes back every 76 years, loses about 10-20 feet (3-6 meters) of ice from its surface on each visit.

This cycle repeats, over and over. After hundreds or thousands of orbits, one of two things usually happens:

- It Becomes a “Dead” Comet: The comet just… runs out of gas. All its volatile ices—the water, the carbon dioxide, the methane—are all gone. All that’s left is a dark, dead lump of rock and dust. It can’t make a coma or a tail anymore.

- It Disintegrates: Sometimes, the heating is just too much. The nucleus is a fragile, loosely-packed pile of ice and rubble. The Sun’s intense heat, or its gravity, can just rip the whole thing apart. It breaks up into a cloud of debris that spreads out along the comet’s original orbit.

This debris is what causes meteor showers. When Earth’s orbit crosses the old path of a “dead” or disintegrated comet, we plow through its leftover dust trail. Those tiny bits of cometary dust burn up in our atmosphere as “shooting stars.”

Can We Ever See These Tails from Earth?

Absolutely! Seeing a comet with your own eyes is one of the greatest experiences you can have in stargazing.

While small comets are found all the time (you need a big telescope to see them), a truly “great” comet comes along every few years or so. These are the ones that get bright enough to see with the naked eye, and they are unforgettable.

Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997 was a mind-blowing example. It was visible for a record-breaking 18 months. More recently, Comet NEOWISE in 2020 was a beautiful sight for all of us in the Northern Hemisphere.

What Makes a Comet So Visible?

It’s all about the coma and the tails. The tiny nucleus is way too small to ever see. What we’re actually seeing is that enormous cloud of gas and dust being lit up by the Sun.

The white dust tail is bright because it’s so huge and is reflecting a ton of sunlight. The blue ion tail is bright because its gases are literally glowing.

The brightness of a comet is famously hard to predict. It all depends on how close it gets to the Sun (more heat = more gas = bigger coma) and how close it gets to Earth (closer just means it looks bigger to us).

What’s the Best Way to See a Comet?

When you hear a bright comet is in the news, the first step is to find out where to look. You’ll need a star chart or an app.

Here are a few tips to give you the best shot:

- Get Away from Lights: This is rule number one. City light pollution will wash out a comet’s faint tail. You need to get to a dark-sky spot.

- Check the Timing: Comets are often most visible in the hours just after sunset or just before sunrise, when they are in a dark sky but the Sun is still close enough to make them active.

- Start with Your Eyes: Just look. Let your eyes adapt to the dark for at least 15 minutes. Don’t look at your phone.

- Use Binoculars: This is the pro-tip. Even a cheap pair of binoculars will be better than a telescope for most comets. They gather more light and have a wide field of view, letting you see the comet and its tail in context.

For the most current information on any visible comets, your best bet is to check with the experts. You can always check official resources like NASA’s comet page for reliable, up-to-date information.

What Have We Learned from Studying Comet Tails?

To scientists, comet tails aren’t just pretty. They are gigantic, waving billboards of data. They’re cosmic laboratories, floating in space, that tell us things we could never learn from here on Earth.

By studying the light from comets, we can use a technique called spectroscopy to figure out exactly what they’re made of. But the tails, specifically, teach us about two very different things: our past and our present.

Are Comets Just “Dirty Snowballs” or Something More?

Oh, they are so much more. They are “time capsules.”

Because they’ve spent 4.6 billion years in the deep freeze, the stuff they’re made of is perfectly preserved. It’s the original, raw material that built our entire solar system.

When we study the dust in a comet’s tail, we are looking at the literal building blocks of planets. We’ve found complex organic molecules—the precursors to life. Many scientists believe that comets, by crashing into a young, sterile Earth, may have delivered a huge portion of our planet’s water and the very organic compounds that helped life get started.

How Do Comet Tails Help Us Understand the Sun?

This is where the ion tail shines. Literally.

The Sun’s solar wind is invisible. We can build and launch expensive spacecraft to measure it, but that just gives us a measurement in one tiny spot.

A comet’s ion tail, on the other hand, is a visible tracer of the solar wind. It’s a windsock the size of a planet. By watching the ion tail, we can see the solar wind in action. We can see it get hit by solar storms (coronal mass ejections), and we can watch it get buffeted and twisted. It lets us measure the solar wind’s speed and direction over a vast area.

In 1986, the Giotto spacecraft bravely flew right through the coma of Halley’s Comet. In 2005, the Deep Impact mission smashed a projectile into a comet just to see what would fly out. And the Rosetta mission spent years actually orbiting a comet, even landing a probe on its surface.

Each of these missions confirmed what we’re learning: comets are a key to our past, and their tails are a key to understanding our Sun’s powerful, present-day influence.

FAQ – What Causes a Comet’s Tail

Why does a comet have two tails?

A comet has two tails because they are formed by different solar forces. The ion tail is created by the solar wind blowing charged gas particles straight away from the Sun, while the dust tail is shaped by the sunlight’s radiation pressure pushing heavier dust particles, resulting in a curved tail.

What is the composition of a comet?

A comet is composed mainly of ice, dust, and rock, often called a ‘dirty snowball.’ Its nucleus contains frozen water, carbon dioxide, methane, ammonia, and other gases, mixed with dust and rocky debris, making it a dark, icy, and rocky cosmic remnant.

How do the tails of comets point in different directions?

The tails point away from the Sun because the solar wind and radiation pressure exert forces that push the ion and dust particles outward from the Sun. The ion tail is always straight and points directly away, while the dust tail curves due to the slower, gentle push of sunlight combined with the comet’s movement.

Can we see comet tails from Earth?

Yes, comet tails can be visible from Earth, especially during bright, well-observed comets like Hale-Bopp or NEOWISE. Visibility depends on the comet’s proximity to the Sun and Earth, and watching from dark sky locations with binoculars often provides the best viewing experience.