You think you know what “big” means.

You’ve stood at the base of a skyscraper or looked out over the Grand Canyon. Maybe you’ve even tried to wrap your head around the size of the Earth. It’s huge. It feels infinite when you’re trying to drive across it.

But the universe doesn’t play by our rules. It operates on a scale so terrifyingly massive that the human brain actually shuts down when trying to comprehend it. We just can’t process the zeros.

Take our Sun. It’s a beast. It accounts for 99.8% of all the mass in our solar system. You could pack 1.3 million Earths inside it like gumballs in a jar. If you drove a car at highway speeds around the equator of the Sun, you wouldn’t sleep in your own bed for six months.

That sounds impressive. It is impressive.

But out there in the deep black, lurking in the dusty corners of the Milky Way, there are monsters. Stars so large they defy the laws of physics as we understand them. If the Sun is a grain of sand, these things are beach balls. If the Sun is a basketball, these things are Mount Everest.

We are going on a hunt. We are going to track down the titans of the galaxy. We will dig into the science, the arguments, and the sheer, mind-bending reality of what are the largest known stars.

Buckle up. It’s going to be a long ride.

More in Celestial Objects Category

Difference Between Meteoroid Meteor Meteorite

What Is Left After a Supernova

Key Takeaways

- Stephenson 2-18 is the current heavyweight champion, with a radius estimated at 2,150 times that of the Sun.

- “Size” is tricky. These stars don’t have solid surfaces; they are giant, puffy clouds of vacuum-thin gas, making measurements incredibly difficult.

- UY Scuti has been dethroned. Once the king, new data suggests it is much closer to Earth and therefore much smaller than we used to think.

- Mass vs. Volume. The largest stars aren’t the heaviest. They are often “red supergiants” spread thin over billions of miles.

- The list keeps changing. Better telescopes and new techniques (like the Gaia mission) constantly rewrite the record books.

Why is Measuring a Star So Incredible Hard?

Before we start naming names, you have to understand the problem.

Why can’t we just say, “Star X is the biggest”?

It’s because we can’t touch them. We can’t fly a tape measure out to the Scutum constellation. We are stuck here on Earth, peering through a soup of atmosphere, trying to measure a glowing dot thousands of light-years away.

To figure out how big a star is, we need two things:

- How wide it looks from Earth (angular diameter).

- Exactly how far away it is.

Here is the catch.

If you get the distance wrong by just a little bit, your size calculation is off by trillions of miles. For decades, we thought certain stars were galactic giants, only to realize they were just closer to us than we assumed.

Then you have the “fuzzy edge” problem.

Look at a picture of Earth. You see a hard line where the ground ends and space begins. Easy.

Red supergiants—the type of stars we are talking about—don’t have that. They are barely holding themselves together. Their outer layers are so thin that they are essentially a vacuum. If you were flying a spaceship into Stephenson 2-18, you wouldn’t crash. You wouldn’t even know you were inside the star for a long time. The gas would just get gradually hotter and thicker until you burned up.

So, when astronomers declare a star the “largest,” they are making a best guess based on where the gas becomes thick enough to block light. It’s like trying to measure the diameter of a fog bank while standing three towns over.

Who Holds the Crown Right Now?

If you want the short answer, here it is: Stephenson 2-18.

This thing is a monster. It resides in a massive cluster of stars called Stephenson 2, located about 20,000 light-years away in the constellation Scutum.

Let’s talk numbers, but let’s make them real.

Stephenson 2-18 has a radius roughly 2,150 times that of the Sun.

I know, “2,150” just sounds like a number. Let’s put it in the center of our solar system.

- Mercury? Gone.

- Venus? Vaporized.

- Earth? swallowed whole.

- Mars? Inside the core.

- Jupiter? Deep inside the star.

- Saturn? Even Saturn and its rings would be engulfed.

If you replaced the Sun with Stephenson 2-18, the surface of the star would extend out past Saturn’s orbit. Light, which moves at 186,000 miles per second, takes hours to cross it.

If you flew a commercial jet around our Sun, it takes roughly six months.

If you flew that same jet around Stephenson 2-18? It would take 500 years.

You would take off, live your entire life, die, and your great-great-great-great-grandchildren would be the ones landing the plane. That is the scale of this object. It shines with the light of 440,000 Suns. It pushes the absolute theoretical limit of how big a star can get before blowing itself apart.

Whatever Happened to UY Scuti?

I can hear you asking this. “Wait, I thought UY Scuti was the biggest?”

If you Googled this question in 2018, you would be right. For years, UY Scuti was the undisputed king of the sky. Textbooks, YouTube videos, and science articles all hailed it as the largest object in the universe.

We thought it was 1,700 times the radius of the Sun, maybe even up to 5,000 times if you pushed the error margins.

Then, the Gaia Mission ruined the party.

Gaia is a space observatory launched by the European Space Agency. Its job is to map the galaxy with insane precision. When Gaia looked at UY Scuti, it found something awkward. The star is closer to Earth than we thought.

Here is the rule of astronomy: If a star looks big, but it’s closer than you thought, it’s actually smaller.

Recalculations dropped UY Scuti down to somewhere between 900 and 1,000 solar radii.

Don’t cry for UY Scuti. It’s still terrifyingly huge. It would still eat Jupiter. But it’s not the king anymore. It’s a perfect example of how science works. We don’t stick to old answers just because we like them. When the data gets better, we change our minds.

The Heavy Hitters: A Tour of the Top Contenders

Stephenson 2-18 isn’t the only titan out there. The leaderboard is crowded, and because measuring these things is so hard, the rankings swap constantly.

Let’s look at the other monsters fighting for the title.

1. WOH G64: The Ghost in the Next Galaxy

This star is lurking in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy orbiting our Milky Way. That makes it incredibly far away—about 160,000 light-years.

WOH G64 is huge, but it’s messy. It is surrounded by a massive doughnut-shaped cloud of dust and gas that it coughed up itself. This dust blocks a lot of light, making it a nightmare to measure. Some estimates put it at 1,540 solar radii. Others suggest it could be over 2,500.

If the high estimates are right, it beats Stephenson 2-18. But most astronomers lean toward the lower numbers these days. It’s a dying star, shrouded in its own funeral veil.

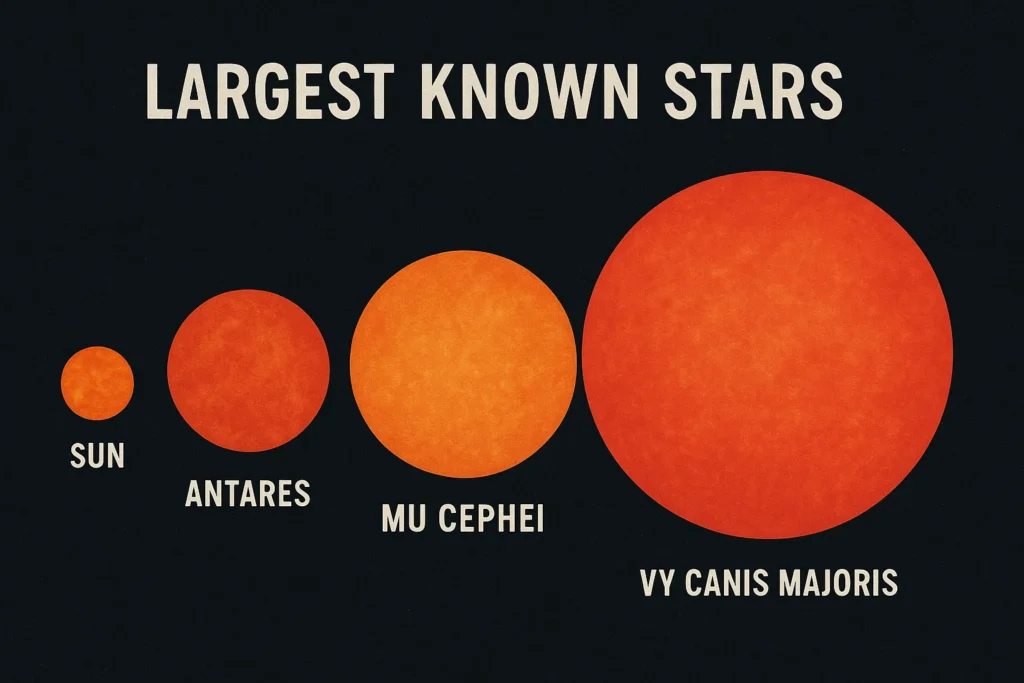

2. VY Canis Majoris: The Old Favorite

Before UY Scuti, there was VY Canis Majoris. This star was the internet celebrity of the 2000s.

It’s located in the constellation Canis Major (The Big Dog). This star is having a violent mid-life crisis. It is a “red hypergiant,” which is exactly as cool as it sounds. It is throwing mass out into space at a rate that shocks scientists.

It has lost half its mass. Imagine the Sun just spitting out half of itself.

Current measurements put it around 1,420 solar radii. It’s lumpy, unstable, and surrounded by complex arcs of nebula. It looks like a cosmic explosion frozen in time.

3. NML Cygni: The Swan’s Giant

Hidden in the Cygnus constellation, NML Cygni is often overlooked. It shouldn’t be.

It sits around 1,639 solar radii. It is one of the most luminous supergiant stars in our vicinity. Like the others, it is hiding behind a curtain of dust, which makes pinning down its exact size a headache.

4. Westerlund 1-26: The Cluster Monster

This star lives in the Westerlund 1 super star cluster. This cluster is like a mosh pit of massive stars.

Westerlund 1-26 is estimated at over 1,500 solar radii. But the interesting thing here is the neighborhood. It is surrounded by hundreds of other massive, blue, young stars. It’s a chaotic environment that tells us a lot about how these giants evolve.

How Do You Build a Star This Big?

Stars aren’t born this big. They swell up. It’s a symptom of old age.

Think of a star as a pressure cooker. Gravity is constantly trying to crush the star inward. The nuclear explosion in the core pushes outward. For most of a star’s life, these two forces are balanced. This is called hydrostatic equilibrium.

But eventually, the fuel runs out.

When a massive star burns through its hydrogen, it switches to helium. Then carbon. Then neon. Then oxygen.

Each time it switches fuels, the core gets hotter. This intense heat pushes the outer layers of the star furiously outward.

The star expands. It cools down as it grows, turning red.

It becomes a Red Supergiant.

This is the final phase. It is the death throes of a cosmic god. The star is frantically trying to stay alive, burning heavier and heavier elements. But it’s a losing battle. It’s blowing itself up like a balloon just before the pop.

And the pop is coming.

Every single star we have mentioned in this article is going to explode. They will go supernova. When they do, they will outshine their entire host galaxy for a few weeks. Stephenson 2-18 will eventually collapse and blast its guts across the universe, leaving behind a black hole or a neutron star.

Is “Big” the Same as “Heavy”?

This is where people get tripped up.

You might assume that Stephenson 2-18 is the most massive star because it’s the largest.

Nope. Not even close.

Think of a beach ball and a bowling ball.

The beach ball is bigger. It takes up more space. But the bowling ball contains more stuff.

Red supergiants are beach balls. They are incredibly diffuse. Stephenson 2-18 might only have 15 to 20 times the mass of the Sun, despite being 2,000 times wider.

If you want the heaviest star (the bowling ball), you have to look at the blue ones.

R136a1 is the current record holder for mass. It weighs in at about 265 times the mass of the Sun. But it’s tiny compared to the red giants—only about 30 times the radius of the Sun.

Why Should You Care About These Distant Giants?

It’s easy to look at these numbers and shrug. “Okay, it’s big. So what?”

Here is why it matters to you, personally.

You are made of them.

I’m serious. Look at your hand. The carbon in your cells, the oxygen in your lungs, the iron in your blood, the calcium in your bones.

None of that existed at the beginning of the universe. The Big Bang only made hydrogen and helium. You can’t build a human out of gas.

So where did the rest come from?

It was cooked.

Inside the cores of stars like Stephenson 2-18 and VY Canis Majoris, atoms are smashed together to create heavy elements. It is a nuclear forge.

But that stuff is trapped in the core. It does no good there.

It needs to get out.

When these giants explode as supernovae, they scatter those elements across the galaxy. They seed the gas clouds that will eventually form new stars and new planets.

Our solar system formed from the debris of a dead giant. We are walking, talking nuclear waste from a star that died billions of years ago. Studying these largest stars is studying our own ancestors.

What About Betelgeuse?

We have to talk about Betelgeuse. It’s the one star everyone knows.

You can see it tonight. Go outside, look for Orion. The bright red star at his shoulder? That’s Betelgeuse.

It’s close—only about 650 light-years away.

Because it’s so close, it’s the only star (other than the Sun) where we can actually see details on the surface. We can see massive bright spots and dark patches.

Is it the largest?

No. It’s roughly 764 times the radius of the Sun.

Compared to Stephenson 2-18, Betelgeuse is a shrimp. But it is our shrimp.

In late 2019, Betelgeuse started dimming. It got significantly darker. People freaked out. Was it about to blow? Was we about to get a front-row seat to a supernova?

Turns out, no. It just burped.

It ejected a massive cloud of dust that blocked its own light. But studying Betelgeuse teaches us how the bigger, more distant giants behave. It is our laboratory.

The Technology That Finds Them

How do we find these things? We don’t just use standard telescopes.

We use something called Interferometry.

Imagine you have a telescope as big as a football field. That would be great, right? But we can’t build mirrors that big. They would crack under their own weight.

So we cheat.

We take two or more smaller telescopes and space them far apart. Then we combine their signals using supercomputers. This tricks the physics into acting like we have one giant telescope the size of the distance between them.

This is how we get the angular diameter of stars like Betelgeuse.

The Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile uses this. It’s our best tool for hunting giants.

But even with this tech, it’s hard.

Dust is the enemy.

The Milky Way is dirty. It’s full of soot and gas. The largest stars love to hang out in the dustiest neighborhoods (because that’s where stars are born).

This is why infrared telescopes are crucial. Infrared light cuts through dust like it’s not even there.

This is why the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is a big deal. It sees in infrared. It’s going to peer into these dusty clusters and likely find stars that we didn’t even know existed.

The record for “largest star” is probably going to be broken in the next ten years.

Can They Get Any Bigger?

Is there a limit? Or can a star just keep growing forever?

Physics says there is a stop sign.

It’s called the Hayashi Limit.

This is a theoretical line on the H-R diagram (a chart astronomers use to classify stars).

If a star tries to get cooler and larger than this limit, it becomes unstable. The outer layers aren’t held by gravity anymore. They just drift away.

Stephenson 2-18 is sitting right on this line.

It is practically daring the laws of physics to stop it.

Some scientists think it might be larger than the limit allows because our theories are slightly wrong. Others think it looks larger than it is because of the “puffy” atmosphere we talked about earlier.

But generally, we think 2,500 solar radii is roughly the ceiling. You can’t build a structure of gas bigger than that. It just falls apart.

A Quick Comparison Chart for the Visual Thinkers

Sometimes you just need the data straight. Here is the current hierarchy of the cosmic heavyweights. Remember, these numbers change as we get better glasses.

- Stephenson 2-18

- Radius: ~2,150 Solar Radii

- Location: Scutum

- The Vibe: The current undisputed king.

- WOH G64

- Radius: ~1,540 – 2,500+ Solar Radii

- Location: Large Magellanic Cloud

- The Vibe: The mysterious outsider with a dust problem.

- Westerlund 1-26

- Radius: ~1,530 Solar Radii

- Location: Ara

- The Vibe: The punk rocker in a crowded mosh pit.

- NML Cygni

- Radius: ~1,639 Solar Radii

- Location: Cygnus

- The Vibe: The quiet giant lurking in the Swan.

- VY Canis Majoris

- Radius: ~1,420 Solar Radii

- Location: Canis Major

- The Vibe: The violent, exploding legend.

The Future of Cosmic Hunting

We are in a golden age of astronomy.

For centuries, we just used our eyes. Then glass lenses. Then mirrors.

Now we are using space-based observatories that can see heat, radio waves, and X-rays.

The Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) is currently being built in the Atacama Desert in Chile.

The name is not a joke. That is its actual name.

It will have a main mirror 39 meters across. It will gather 100 million times more light than the human eye.

When this thing turns on later this decade, our list of largest stars is going to get a shake-up. We might find red supergiants in other galaxies that make Stephenson 2-18 look average.

For more on how these future telescopes will change the game, check out this deep dive from NASA’s Universe Exploration.

So, What Does It All Mean?

It’s easy to feel small after reading this.

You are small. We all are.

But there is something powerful about the fact that we found them.

We are tiny biological machines on a wet rock, yet we figured out how to measure a ball of fire 20,000 light-years away that is larger than our entire solar system.

We know its temperature. We know what it’s eating. We know how it’s going to die.

That’s the triumph. The stars are big, but the human curiosity that found them is arguably more impressive.

So next time you are out at night, look south toward the Scutum constellation (it’s near Aquila, the Eagle). You won’t see Stephenson 2-18. It’s too far and too dim for your eyes.

But you know it’s there.

A silent, glowing red titan, churning in the dark, waiting for the day it finally lets go and lights up the galaxy.

Until then, it remains the king. But in astronomy, the king never keeps the crown for long.

FAQ – What Are the Largest Known Stars

Why is measuring the size of distant stars so difficult?

Measuring the size of distant stars is challenging because they have no solid surfaces, making it hard to determine their boundaries. Additionally, their vast distance from Earth, atmospheric interference, and the fuzzy, gas-rich outer layers complicate accurate measurements, which depend on knowing both the star’s apparent size and its exact distance.

Has UY Scuti always been considered the largest star?

No, UY Scuti was considered the largest star until the Gaia Mission revealed it is much closer to Earth than previously thought, reducing its estimated size from around 1,700-5,000 solar radii to between 900 and 1,000 radii. This change exemplifies how improved data can revise astronomical measurements.

What is the difference between the size and the mass of stars like Stephenson 2-18?

Size refers to the volume or radius of a star, which can be enormous in red supergiants like Stephenson 2-18, while mass is the amount of matter contained within the star. Red supergiants tend to be diffuse with large radii but relatively low mass compared to more compact stars like blue giants, which are more massive but smaller in volume.