You can’t trust your eyes. That is the first lesson of astronomy. When you stand in your backyard and look up at the Orion Constellation, you see a flat, two-dimensional sheet. The stars look like diamonds pinned to a piece of black velvet. One star shines brightly; another glows faintly. Your brain tells you the bright one must be closer.

Your brain is wrong.

That bright star might be a candle sitting on your front porch, metaphorically speaking. The faint one could be a searchlight located three counties over. Without depth perception, the universe is just a confusing scatter of lights. For most of human history, this optical illusion trapped us. We had no idea if the universe ended just past Saturn or if it stretched on forever.

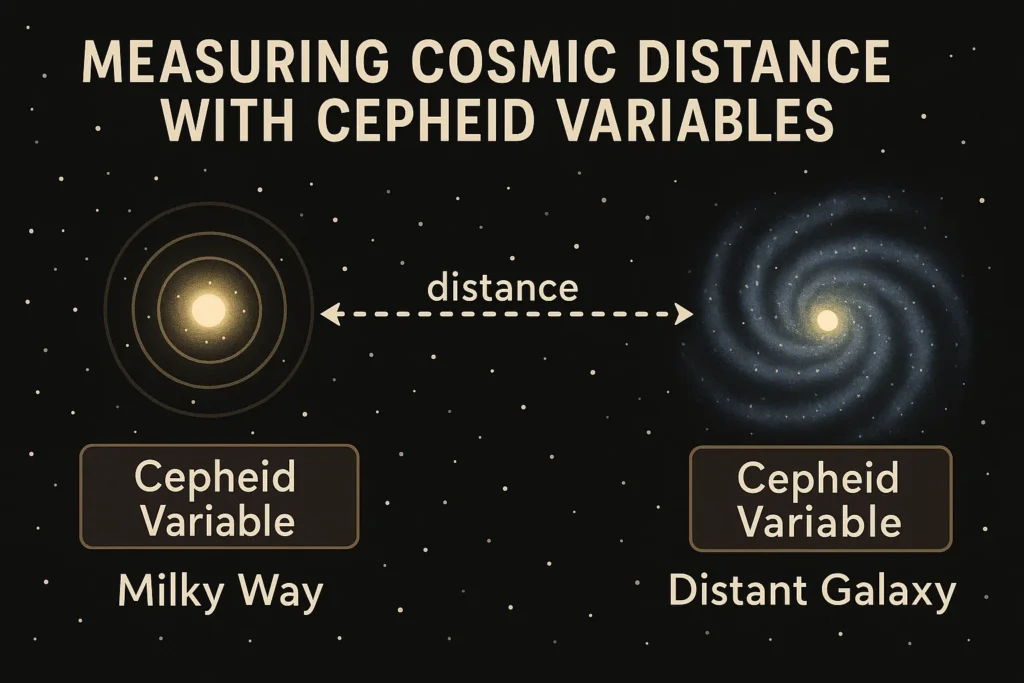

We needed a ruler. Not a physical one, but a quirk of physics that would let us crack the code of deep space. That quirk turned out to be a specific, pulsing type of star. Measuring cosmic distance with cepheid variables became the key that unlocked the cage. It transformed astronomy from a guessing game into a precision science.

More in Celestial Objects Category

Will Our Sun Become a White Dwarf

Why Are Neutron Stars So Dense

Key Takeaways

- The Pulse is the Key: Cepheid variables don’t shine steadily; they expand and contract like a beating heart.

- Leavitt’s Law: Henrietta Swan Leavitt discovered that the time it takes a Cepheid to pulse tells you exactly how bright it actually is.

- Standard Candles: By knowing a star’s true brightness, astronomers can compare it to its apparent brightness to calculate precise distance.

- Breaking the Milky Way: This method proved that the “nebulae” we saw were actually distant galaxies, expanding the known universe overnight.

- The Cosmic Ladder: Cepheids act as the crucial bridge between local geometry measurements and deep-space supernovae.

Why is gauging distance in space such a nightmare?

Imagine you are driving on a desert highway at 2:00 AM. It’s pitch black. You see a single point of light ahead. Is it a motorcycle tail light a hundred yards in front of you? Or is it the porch light of a farmhouse five miles away?

You cannot know. You lack the crucial data point: intrinsic luminosity. If you knew for a fact that the light was a 60-watt porch bulb, you could measure how faint it looks to your eye and calculate exactly how far away the farmhouse sits. Physics dictates that light fades in a very specific way over distance.

But without knowing the wattage, you are guessing.

Astronomers call this the difference between apparent magnitude (what we see) and absolute magnitude (the reality). For nearby stars, we use geometry. We use parallax—measuring the shift of a star against the background as Earth moves around the Sun. But parallax fails once you leave our immediate stellar neighborhood. The angles get too small. The triangle collapses.

For centuries, we were stuck. We needed a beacon. We needed a star that effectively shouted, “I am a 100-watt bulb!” across the void.

Who actually cracked the code?

The hero of this story isn’t a man with a telescope on a mountain. It was a woman sitting at a desk in Massachusetts, examining glass plates with a magnifying glass.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt worked at the Harvard College Observatory in the early 1900s. She was one of the “Harvard Computers”—women hired to perform the tedious, mathematical grunt work that the male astronomers didn’t want to do. They paid her pennies. She was deaf. She received little recognition in her time.

Yet, she possessed a mind capable of seeing patterns where others saw only noise.

Leavitt focused her efforts on the Small Magellanic Cloud, a cluster of stars visible from the Southern Hemisphere. She spent her days cataloging thousands of stars. Among them, she noticed a handful that refused to stay static. They brightened, dimmed, and brightened again.

How did a simple pattern change history?

Leavitt realized something vital about the Small Magellanic Cloud. Because the cloud itself was so far away, she could assume all the stars inside it were roughly the same distance from Earth. It’s like looking at a flock of birds; one bird isn’t significantly closer to you than another.

This removed distance as a variable.

She plotted the stars on a graph. On one axis, she put the “period”—the time it took for the star to cycle from bright to dim to bright. On the other axis, she put the brightness.

The resulting line was undeniable. The longer the pulse, the brighter the star.

She didn’t just find a correlation; she found a physical law. If you find a Cepheid anywhere in the universe and time its pulse, you know its true wattage. Leavitt gave us the standard candle.

What is physically happening inside a Cepheid Variable?

So, why do these things blink? Is it a binary system where one star passes in front of another?

No. These stars are breathing.

A Cepheid variable is a dying supergiant. It has burned through its hydrogen fuel and is currently in a very unstable phase of life. It is massive, hot, and violent. The pulsation is a mechanical war between gravity pulling in and pressure pushing out.

Can we visualize the engine?

Think of a pot of boiling water with a heavy lid.

- The Squeeze: Gravity pulls the star’s outer layers inward. This compresses the gas.

- The Ionization: As the gas compresses, it gets hot. Really hot. This heat strips electrons off helium atoms in the star’s atmosphere.

- The Trap: This ionized helium becomes opaque. It acts like a thick blanket, trapping the light and heat trying to escape from the core.

- The Push: Pressure builds up under the “blanket.” Eventually, the pressure overpowers gravity. It blasts the outer layers outward. The star physically expands and glows fiercely bright.

- The Release: As it expands, the gas cools. The helium grabs its electrons back and becomes transparent again. The heat escapes into space.

- The Reset: The pressure drops, gravity wins again, and the star collapses back down to start the cycle over.

This is the Kappa Mechanism. It’s a stellar valve engine. And it runs with the precision of a Swiss watch.

How do astronomers use this to measure distance?

You might assume this is all automated by computers now. While algorithms help, the logic remains human.

First, you have to find them. Astronomers take photos of the same galaxy night after night. They “blink” the images—rapidly switching between them—looking for any pixel that changes intensity.

Once they spot a candidate, the real work begins.

They track the star over weeks or months. They build a “light curve,” a graph showing the rise and fall of illumination. They pinpoint the exact period. Let’s say this specific star pulses exactly every 45 days.

What happens after we get the timing?

We look at Leavitt’s Law (now calibrated with modern technology). The graph tells us that a 45-day period corresponds to an absolute magnitude of, say, -6.0.

Now we have the two critical numbers:

- Apparent Magnitude: How faint the star looks in our telescope.

- Absolute Magnitude: How bright the star actually is (thanks to the pulse).

We plug these into the distance modulus equation. It’s a straightforward piece of algebra. The difference between the two numbers reveals the distance. If a 1000-watt bulb looks like a firefly, it must be miles away. If a Cepheid supergiant looks like a faint dot, it must be millions of light-years away.

Why was this discovery so controversial?

We take galaxies for granted today. We know we live in the Milky Way, which is just one of billions of galaxies.

But in 1920, this was a radical, heretical idea. The scientific consensus held that the Milky Way was the entire universe. The spiral shapes astronomers saw? They thought those were just “protostars” forming nearby.

This led to the “Great Debate” between astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis. Shapley argued the universe was small and contained only us. Curtis argued those spirals were “island universes” far outside our own.

They argued with rhetoric and theory. They needed proof.

How did Hubble settle the argument?

Edwin Hubble, armed with the massive Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson, pointed his lens at the Andromeda Nebula in 1923. He wasn’t looking for a debate; he was looking for novae (exploding stars).

He found a star that he initially marked with an “N” for nova. But later, checking previous plates, he realized it wasn’t exploding. It was pulsing. It was a Cepheid.

He crossed out the “N” and wrote “VAR!” in red ink.

He timed the pulse. He applied Leavitt’s logic. The math was merciless. The star was not inside the Milky Way. It was nearly a million light-years away (we now know it’s 2.5 million).

The universe exploded in size instantly. We realized we weren’t the whole show; we were just one tiny island in a boundless archipelago.

What is the “Cosmic Distance Ladder”?

Astronomers often talk about a “ladder.” This is because you can’t use one ruler for the whole universe. You need a series of overlapping methods, where each one verifies the next.

Cepheids sit right in the middle. They are the linchpin.

- Rung 1: Geometry. We use parallax to measure the distance to the closest Cepheids inside our own galaxy. This confirms that Leavitt’s math works locally.

- Rung 2: Cepheids. We use those calibrated Cepheids to measure the distance to nearby galaxies.

- Rung 3: Type Ia Supernovae. These are massive explosions that are visible much further out than Cepheids. We find a galaxy that has both a Cepheid and a recent supernova. We use the Cepheid to determine the distance, which tells us the true brightness of the supernova.

- Rung 4: Redshift. We use the supernova data to calibrate the expansion of the universe itself.

If the Cepheid rung snaps, the whole ladder falls apart. Our understanding of the Big Bang, the age of the universe, and dark energy all rely on these pulsing stars being interpreted correctly.

Are there problems with this method?

Nothing in science is perfect. Measuring cosmic distance with cepheid variables comes with baggage.

The biggest enemy is dust. Space is dirty. It is filled with clouds of gas and microscopic grains of carbon and silicon. When light passes through this dust, it gets dimmer. It also gets redder. This is called “extinction.”

If you don’t account for dust, you will think the Cepheid is fainter (and therefore further away) than it really is.

How do we fight the dust?

Modern astronomers have moved beyond visible light. They now observe Cepheids in the infrared spectrum. Infrared waves are longer; they slip through dust clouds like they aren’t even there. This gives us a much “cleaner” view of the star’s true brightness.

Another issue is “metallicity.” Stars aren’t all made of the same stuff. Younger stars have more heavy metals (elements heavier than helium) than older stars. This chemical makeup changes the opacity of the gas, which changes the pulse rate slightly. Astronomers have to apply correction factors based on the chemical flavor of the galaxy they are studying.

See how the Webb Telescope is refining these measurements today.

Why is the “Hubble Tension” keeping astronomers awake at night?

You might think this is a solved problem. We have the ruler; we have the stars. Done deal, right?

Wrong. We are currently in the midst of a crisis.

We have two ways to estimate how fast the universe is expanding (the Hubble Constant).

- We can look at the “baby picture” of the universe—the Cosmic Microwave Background—and project forward to today.

- We can measure the local universe using Cepheids and Supernovae.

Here is the problem: The numbers don’t match.

The Cepheid method says the universe is expanding significantly faster than the Cosmic Microwave Background method predicts. This isn’t a calculation error. Both sides have checked their math a thousand times. The error bars do not overlap.

This is the “Hubble Tension.”

It implies that either our understanding of the early universe is flawed, or something weird is happening in the modern universe that we don’t understand. Maybe there is a new particle. Maybe “Dark Energy” is changing over time.

Cepheids are at the center of the storm. Astronomers are scrutinizing them closer than ever, trying to see if we made a mistake in the calibration.

How is the James Webb Space Telescope changing the game?

The Hubble Space Telescope was amazing, but it had limits. When looking at distant galaxies, pixels blur together. A Cepheid might blend in with the light of a neighboring star, making it look brighter than it is. This “crowding” could skew the data.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is sharper. Much sharper.

JWST can resolve individual Cepheids in galaxies that looked like fuzzy blobs to Hubble. It can separate the variable star from its neighbors. Early data from JWST seems to confirm the Hubble Space Telescope’s measurements were actually quite accurate.

This is both good and bad news. It’s good because it means we are good at measuring. It’s “bad” because it means the Hubble Tension is real. The physics really is broken somewhere.

Why does this matter to you?

Why should you care about pulsing stars millions of miles away?

Because it defines where you are. Before we understood measuring cosmic distance with cepheid variables, we were trapped in a small box. We were the center of attention. Leavitt and Hubble humbled us. They showed us a universe so vast that it defies comprehension.

It also tells us where we are going. By measuring how fast these galaxies are moving away from us (calibrated by Cepheids), we learned the universe had a beginning. We learned about the Big Bang. We learned that the universe will likely end in a cold, dark expansion.

These stars are the ticking clocks that tell us the timeline of existence.

Conclusion

The night sky is a deceptive beauty. It hides its depth. But thanks to the tireless work of Henrietta Leavitt and the astronomers who followed her, we learned to read the hidden signals.

Cepheid variables are more than just stars; they are the milestones of the cosmos. They pulse with a rhythm that resonates across the void, allowing us to bridge the gap between our tiny home and the furthest reaches of space. As we continue to refine our measurements and stare deeper into the abyss with new tools, these faithful lighthouses remain our best guide through the dark.

We are still mapping the highway. We are still reading the signs. And the universe keeps getting bigger.

FAQ – Measuring Cosmic Distance with Cepheid Variables

Why can’t we trust our eyes when observing stars in the sky?

Our eyes cannot accurately perceive the depth and distances of stars, making it difficult to determine how far away they are without additional measurement methods.

How did Henrietta Swan Leavitt contribute to our understanding of the universe?

Henrietta Swan Leavitt discovered the relationship between the pulsation period of Cepheid stars and their luminosity, enabling astronomers to measure distances across the universe accurately.

What is the physical process behind the pulsation of Cepheid variables?

Cepheid pulsations are caused by the ionization and recombination of helium in the star’s atmosphere, creating a self-sustaining cycle of expansion and contraction known as the Kappa Mechanism.

What is the Hubble Tension and why does it matter?

The Hubble Tension refers to the disagreement between measurements of the universe’s expansion rate using early universe data and local observations, suggesting possible gaps in current understanding of cosmology.