I still remember the first night I actually found the Hercules Cluster. I wasn’t using a fancy computerized telescope that slews to targets with a robotic whir. I was in my backyard, freezing, wrestling with a manual Dobsonian scope, trying to hop from star to star using a dim red flashlight and a paper chart. When I finally swept over M13, it didn’t look like a star. It looked like a smudge of gray fuzz on a black canvas. But when I swapped in a high-power eyepiece, that smudge exploded. It resolved into thousands of tiny, diamond-dust pinpricks packed so tight my brain couldn’t process it.

Compare that to the Pleiades, which I’d looked at an hour earlier. That was bright, blue, and spread out—like someone spilled a handful of gems on a table.

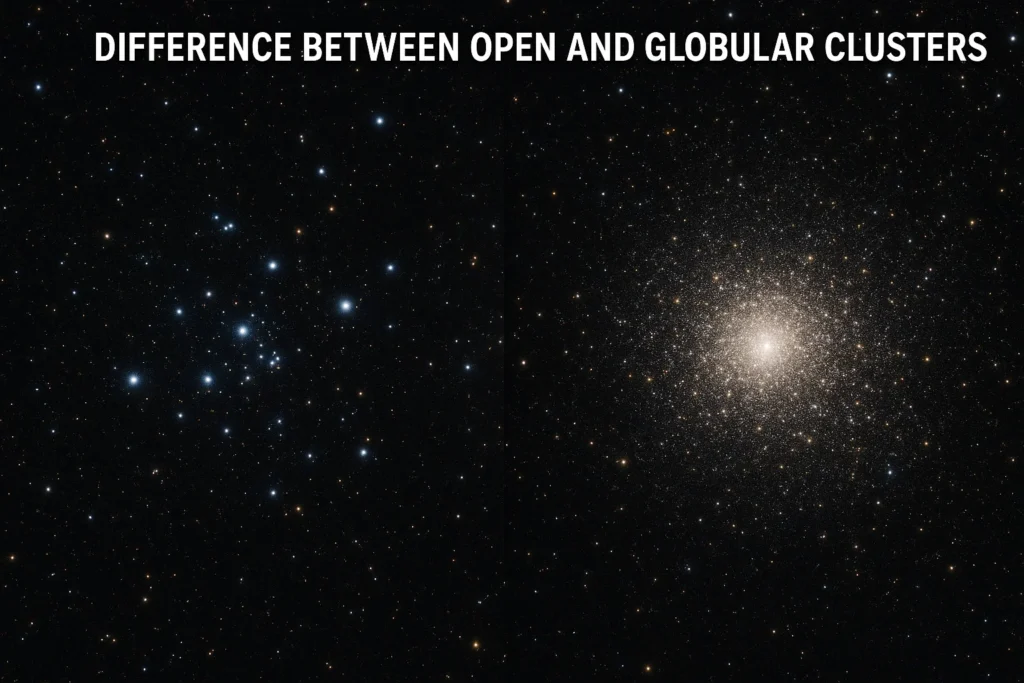

Both are technically “star clusters.” But calling them the same thing is like saying a kindergarten class and a retirement community are the same because they’re both “groups of people.” They aren’t just different looking; they are distinct beasts entirely.

If you’ve ever looked up and wondered why some star groups look like scattered glitter while others look like tight swarms of angry bees, you’ve hit on one of the biggest divides in astronomy. Getting a handle on the difference between open and globular clusters isn’t just about categorizing dots in the sky. It’s about understanding the violent, messy history of how our galaxy grew up.

More in Category:

Will Our Sun Become a White Dwarf

Why Are Neutron Stars So Dense

Key Takeaways

- Open Clusters are the youngsters; they hang out in the spiral arms (the galactic disk) and are full of hot, blue stars.

- Globular Clusters are the ancient relics; they live in the “halo” hovering around the galaxy and are packed with old, red stars.

- Gravity is the main separator: Globulars are tightly bound survivors, while open clusters are loose groups that will eventually drift apart.

- Chemical Composition tells the story: Open clusters are metal-rich (like our Sun), while globulars are metal-poor fossils from the early universe.

- Population Type matters: Open clusters are Population I (new gen); globulars are Population II (old guard).

So, What Exactly Are Star Clusters and Why Should You Even Care?

Think of star clusters as families. Stars rarely form alone in the dark void. Gravity is a hoarder; it pulls vast clouds of gas and dust together until they collapse under their own weight. When this happens, you don’t just get one star. You get a litter.

These stars are siblings. They were born from the same cloud, at the same time, from the same chemical soup. This is why astronomers love them. If I look at a random star in the sky, I have to guess its age based on complex models. But in a cluster? I know they are all the same age. It’s the perfect control group.

But here is where the story splits. Depending on when and where that cloud collapsed, you get two totally different outcomes. One path leads to a loose, chaotic group of young stars. The other leads to a dense, spherical city of ancient stars. Understanding this split is the key to reading the night sky.

How Do You Spot an Open Cluster Without a Telescope?

You’ve probably seen one without realizing it. Go outside in winter and look at Taurus. See that tiny little dipper-shaped group of stars on the bull’s shoulder? That’s the Pleiades (M45). Look at the ‘V’ shape of the bull’s face. That’s the Hyades.

Open clusters are messy. They don’t follow rules. They are irregular, sprawling groups that can hold anywhere from a few dozen to a few thousand stars. They don’t look like balls; they look like random patterns. Some people call them “galactic clusters” because they stick strictly to the flat plane of our galaxy’s disk.

If you see a knot of stars that looks brighter and denser than the background field but still resolves easily into individual points, you are looking at an open cluster. They are the showpieces of the binocular world.

Are they just random stars that happen to be close?

It looks that way, but no. Gravity holds them together, but just barely. Think of an open cluster as a temporary alliance. These stars are currently traveling through space together, but they aren’t bound tightly enough to survive the long haul.

They are young—cosmically speaking. The Pleiades are only about 100 million years old. That sounds old to us, but the Sun is 4.6 billion years old. These stars are toddlers. Because they are so young, you’ll often see wisps of blue nebulosity around them in long-exposure photos. That’s the leftover dust from their birth that they haven’t blown away yet.

What Makes Globular Clusters the “Seniors” of the Galaxy?

Now let’s talk about the heavy hitters. If open clusters are chaotic kindergartens, globular clusters are the fortified cities of the ancient world.

A globular cluster is a massive, spherical ball of stars. We aren’t talking about a few thousand stars here. We are talking about hundreds of thousands, sometimes over a million, all crammed into a space that might be only 100 light-years across.

Gravity here is intense. In the core of a globular cluster, stars are packed so tight that if Earth orbited a star in the middle, our night sky wouldn’t be dark. It would be blazing with thousands of stars brighter than the full moon. You could read a book at midnight.

Why do they look like fuzzy snowballs?

That’s the classic description. Through a small telescope, a globular cluster looks like a comet head without a tail, or a dandelion puff. They look this way because the star density increases dramatically toward the center.

You won’t find gas or dust here. These clusters used all that up billions of years ago. These are clean environments, populated solely by stars that have been buzzing around the cluster center like angry bees for 10 to 13 billion years. They are the survivors of the early universe.

Location, Location, Location: Where Do They Hang Out?

This is the biggest giveaway. The geography of the Milky Way is segregated, and where a cluster lives tells you everything about its identity.

Open clusters are suburbanites. They live in the galactic disk—the flat, spiral part of the Milky Way where we live. Specifically, they hang out in the spiral arms. This makes sense. The spiral arms are where the density waves compress gas clouds to trigger new star formation. Since open clusters are young, you find them where the action is.

Globular clusters are the hermits. They inhabit the “halo.”

Do they ever mix?

Not really. Imagine the galaxy is a fried egg. The yolk is the core, and the white is the flat disk. The open clusters are like pepper sprinkled only on the white part. The globular clusters are different; imagine a swarm of bees buzzing around the entire egg in a giant sphere, flying above and below it.

Because they orbit in this vast halo, plunging through the disk only occasionally, we know they formed before the Milky Way flattened out into a spiral. They are relics from the chaotic formation of the galaxy itself.

How Does Age Define the Difference?

Age is the ultimate separator. We are talking about a generation gap that spans the history of the cosmos.

Open clusters are the new kids on the block. Some, like the Double Cluster in Perseus, are only a few million years old. They are fresh out of the stellar womb. They formed from the gas that exists in the galaxy right now.

Globular clusters are nearly as old as the universe itself. We date them at 12 to 13 billion years old. They formed when the universe was just getting started. When you look at M13, you are looking at light from objects that were shining before Earth even existed.

Why the color difference? Blue vs. Red?

Take a look at a photo of the Pleiades. It’s overwhelmingly blue. Now look at Omega Centauri. It’s gold and red.

Color is a proxy for mass and temperature. Blue stars are massive, hot, and burn through their fuel like a gas-guzzling SUV. They live fast and die young—often exploding as supernovae after just a few million years. Because open clusters are young, these massive blue monsters are still alive and dominating the light profile.

In globular clusters, those blue giants died out billions of years ago. They are long gone. What’s left are the efficient hybrids—the low-mass yellow and red stars that sip their fuel slowly. These stars live for tens of billions of years. When you view a globular, you are seeing the collective glow of a million dying red giants and stable red dwarfs.

What About the “Chemical DNA”?

Astronomers have a weird habit of calling anything heavier than helium a “metal.” It’s confusing, but stick with me.

Stars in open clusters are “metal-rich” (Population I). They formed from gas clouds that were already polluted by the guts of dead stars. Previous generations of stars lived, died, and exploded, spewing carbon, oxygen, iron, and silicon into the galaxy. Our Sun is a Population I star. This is why we have rocky planets. You need those heavy metals to build an Earth.

Globular clusters are “metal-poor” (Population II). They formed so long ago that the universe was basically just hydrogen and helium. There wasn’t much “pollution” yet. Because of this, it’s highly unlikely you’d find an Earth-like planet in a globular cluster. There just wasn’t enough iron or silicon in the mix when those stars formed to build a rock you could stand on.

The Battle with Gravity

The ultimate fate of a cluster comes down to a tug-of-war between its own gravity and the tidal forces of the galaxy.

Open clusters are losing this war. They are loosely packed. As they orbit the galaxy, they drift past giant molecular clouds or get tugged by spiral arms. These gravitational bumps strip stars away from the edges. Over a few hundred million years, the cluster evaporates. The stars drift apart and get lost in the general background of the galaxy. Our Sun likely formed in an open cluster that dissolved billions of years ago. We are a lost sibling.

Globular clusters are winning. They are so dense and massive that their self-gravity locks them together like a vault. They can shrug off the tidal forces of the galaxy. Sure, they lose a star here and there, but as a structure, they are incredibly stable. They have survived for 13 billion years, and they will likely survive for billions more.

Which Ones Should You Target Tonight?

You don’t need a massive observatory to see this difference. A pair of 10×50 binoculars is actually my favorite tool for open clusters, while a small telescope (even a 4-inch) shines on globulars.

The Best Open Clusters

- The Pleiades (M45): It’s the undisputed king. In binoculars, it’s startlingly beautiful. You can see the distinct blue tint of the stars.

- The Double Cluster: Located between Cassiopeia and Perseus. It’s two clusters side-by-side. In a low-power telescope, it looks like diamond dust spilled on black velvet. It’s dense for an open cluster, but clearly not a ball.

- The Wild Duck Cluster (M11): A summer favorite in Scutum. It’s one of the richest open clusters, packed so tight it almost looks globular, but its location in the disk gives it away.

The Best Globular Clusters

- M13 (Hercules): The northern hemisphere standard. It’s easy to find. In a 6-inch scope, you can start to resolve the outer stars, giving it a grainy, 3D appearance.

- Omega Centauri: If you live south of 35 degrees latitude, you have to see this. It’s massive. It’s actually so big that some astronomers think it’s not a cluster at all, but the core of a dwarf galaxy the Milky Way ate long ago.

- M22: In Sagittarius. It’s looser than M13 and sits right in front of the rich milky way background. It’s closer to us, so the stars resolve easier.

How These Clusters Rewrite History

We owe a lot to these starry blobs. Back in the early 1900s, we didn’t know where we fit in the universe. An astronomer named Harlow Shapley used globular clusters to figure it out.

He noticed something odd: globular clusters weren’t scattered evenly. They were mostly bunched up in one part of the sky, toward Sagittarius. He realized they were orbiting the center of the galaxy. By measuring the distance to them, he triangulated the center of the Milky Way and realized—shockingly—that we weren’t in the middle. We were out in the boondocks.

Open clusters, on the other hand, trace out the spiral arms. By mapping them, we figured out the shape of the pizza we live on.

If you want to get into the nitty-gritty physics of how these stars interact, NASA’s Hubble Site has some incredible breakdowns and imagery that go deeper than I can here.

The Bottom Line

The night sky isn’t static. It’s a story of evolution, violence, and survival. When you look at the difference between open and globular clusters, you are seeing the contrast between the galaxy’s vibrant youth and its enduring ancestry.

Open clusters are the party towns—bright, energetic, temporary, and full of live-fast-die-young stars. Globular clusters are the ancient ruins—solemn, tightly knit, and guarding the secrets of the universe’s first epoch.

So next time it’s clear, grab your optics. Find the Seven Sisters, then swing over to the Great Cluster in Hercules. Don’t just look for fuzzy spots. Look for the difference. It’s the best history lesson you’ll ever get.

FAQs – Difference Between Open and Globular Clusters

What is the main difference between open and globular star clusters?

Open clusters are young, loose groupings of stars found in the spiral arms of the galaxy, mainly consisting of blue, hot, and metal-rich stars. Globular clusters are old, densely packed spherical collections of stars located in the galactic halo, comprised mostly of red, cooler, and metal-poor stars.

How can I identify an open cluster in the night sky without a telescope?

Open clusters appear as irregular, sprawling groups of stars that are brighter and denser than the background field, often visible to the naked eye or through binoculars, such as the Pleiades and the Hyades in the constellation Taurus.

Why do globular clusters look like fuzzy snowballs or puffballs?

Globular clusters look like fuzzy snowballs because their stars are densely packed toward the center, creating a spherical shape with a bright core and a more diffuse outer region, observable through small telescopes.

How does gravity influence the survival of open and globular clusters?

Gravity causes open clusters to gradually lose their stars as they orbit through the galaxy, eventually dispersing, while the dense self-gravity of globular clusters makes them highly stable, allowing them to survive for billions of years despite tidal forces.