You’re outside on a crisp, clear night. You look up, and whoosh—a brilliant white streak flashes across the velvet black sky.

“Shooting star!” you yell.

We’ve all been there. It’s a magical, fleeting moment. But then, the next day, you hear a news report about a meteor shower peaking. Or you see a documentary about scientists hunting for meteorites in Antarctica. Or maybe you read a headline about a meteoroid that’s going to pass close to Earth.

Wait. What?

It’s a jumble of words that sound almost identical, and frankly, it’s one of the most common mix-ups in all of science. It’s completely understandable to feel a bit fuzzy on which is which. Are they all the same thing?

No. But they’re all parts of the same story.

Think of it this way: it’s the life cycle of a single object. Like a tadpole, a froglet, and a frog. Or, to be less… amphibious… think of water. Water can be an ice crystal in a cloud, a raindrop falling, or a puddle on the ground. Same H2O, but we call it something different based on where it is and what it’s doing.

If you’ve ever wanted to finally, once and for all, lock in the difference between meteoroid, meteor, and meteorite, this is the place. We’re going to clear it all up. No dense academic-speak, no impossible-to-pronounce classifications (okay, maybe a few). Just the simple, straight-up story of a rock from space.

More in Celestial Objects Category

Difference Between Gas Giant and Star

Difference Between Ice Giant and Gas Giant

Key Takeaways

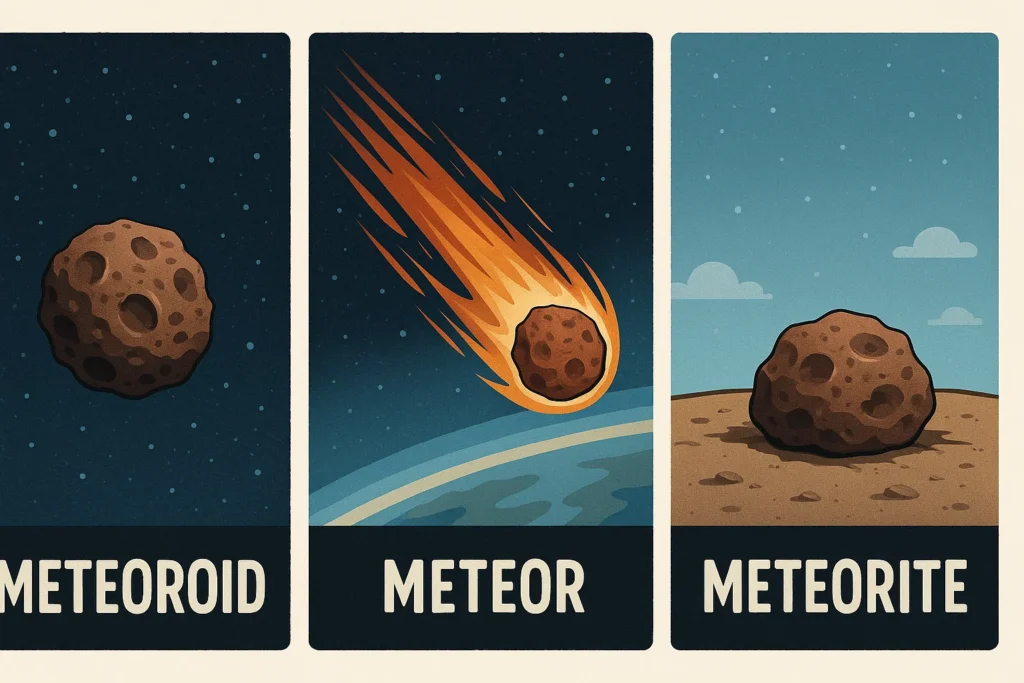

Look, if you’re in a hurry, here’s the “cheat sheet.” This is the core of it. If you remember nothing else, remember this:

- A Meteoroid is a chunk of rock or metal just floating out in the void of space. Think “oid” is in the void.

- A Meteor is the streak of light—the “shooting star” event—that happens when that rock enters our atmosphere and burns up.

- A Meteorite is any piece of that rock that actually survives the whole fiery ordeal and hits the ground.

That’s the entire concept. It’s a name change based on location: Space, Atmosphere, or Ground.

Okay, So What’s the Simple Answer, Really?

Let’s just hammer this point home, because it’s the foundation for everything else. The only thing that separates these three words is perspective. Our perspective.

Imagine a chunk of reddish, iron-rich rock. It’s the size of your fist. For the last four billion years, it’s been tumbling silently through the blackness of space, orbiting the Sun. At this point in its story, it’s a meteoroid. It’s just… out there.

But its orbit isn’t stable forever. Eventually, it crosses paths with a certain blue-white planet. Earth.

Our planet’s massive gravity grabs it. The rock, which was cruising at, say, 30,000 miles per hour, slams into the top of our atmosphere. It’s like hitting a brick wall made of air. This impact doesn’t just create friction; it compresses the air in front of it so violently that the air itself flashes into a brilliant streak of plasma, hotter than the surface of the Sun.

That visible streak, the event we point at and make a wish on, is the meteor. The rock itself is vaporizing, but the light is the superheated air it’s tearing through.

But what if this rock is tough? Or it was bigger, maybe the size of a bowling ball to start? It’s a fiery, ablating (melting) mess, but it’s plowing through. Most of it burns away, but one small, charred, pockmarked piece makes it all the way down. It slows, tumbles, and finally thunks into a farmer’s field in Nebraska.

That rock—the one you can now pick up, the one that’s cool to the touch—is a meteorite.

One object. Three names. It was a meteoroid, it created a meteor, and now it is a meteorite.

So, What Exactly Is a Meteoroid Floating Around Up There?

It all starts here, in the cold, silent vacuum of space. A meteoroid is, for all intents and purposes, space debris. It’s a natural object, a chunk of rock or metal, or both, orbiting the Sun.

But where do they come from? And what makes them different from those other space rocks?

Where do these space rocks even come from?

They aren’t just born from nothing. They’re the leftovers. The crumbs. The cosmic shrapnel from the 4.6-billion-year-old construction project that built our solar system.

Most meteoroids that cross Earth’s path have two primary sources:

- The Asteroid Belt: This is the big one. Between Mars and Jupiter, there’s a massive, chaotic ring of millions of rocky bodies called asteroids. They range from the size of a car (which, as we’ll see, blurs the line) to Ceres, a dwarf planet 600 miles wide. On the cosmic timescale, these asteroids are always bumping into each other, and these collisions send showers of smaller fragments—meteoroids—flying off in all directions.

- Comets: This is the other major source. Comets are the “dirty snowballs” of the solar system, originating from the frigid, distant regions of the Kuiper Belt (beyond Neptune) or the even more distant Oort Cloud. They’re a loose conglomeration of ice, dust, and rock. When a comet’s long, looping orbit brings it close to the Sun, the heat works on it. The ice turns directly into gas, blowing off dust and rock. This process leaves a dense trail of debris, a “river of rubble,” along the comet’s entire orbital path.

Are we talking about giant boulders or tiny dust specks?

Both. And everything in between.

The official, and slightly arbitrary, line drawn by scientists is this: a meteoroid is any of this debris between the size of a microscopic dust grain and one meter (about 3.3 feet) across.

This size is the only thing that separates it from an asteroid.

- Asteroid: Anything larger than one meter across.

- Meteoroid: Anything smaller than one meter across.

It’s a human-made classification, but it’s useful. So, if a 50-foot rock is heading for Earth, astronomers will call it an “asteroid.” If a one-foot rock is doing the same, they’ll call it a “meteoroid.”

This means that a tiny meteoroid is just a microscopic asteroid. And a small asteroid is just a really, really big meteoroid.

What’s this stuff actually made of?

Not all space rocks are created equal. Their composition is a massive clue that tells scientists where they came from and what the early solar system was like.

Imagine a giant, ancient “parent body” asteroid, hundreds of miles wide. When it first formed, it was molten. Just like on Earth, the heavy stuff sank. Dense, heavy metals like iron and nickel migrated to the center to form a metallic core, while the lighter, rocky silicates “floated” to the top to form a mantle and crust.

Now, imagine that giant, differentiated body gets shattered by a massive impact billions of years ago. The debris from that collision would create all the different types of meteoroids we find:

- Stony Meteoroids (Chondrites & Achondrites): These are the most common, making up over 90% of all meteorites found. They are pieces of the rocky crust and mantle of those parent bodies.

- Iron Meteoroids: These are the heavy hitters. They are literal chunks of the metallic core of a shattered world. They are incredibly dense and made almost entirely of iron and nickel.

- Stony-Iron Meteoroids: This is the rarest and, in my opinion, most beautiful group. They come from the boundary, the exact layer between the metallic core and the rocky mantle. They are a stunning, otherworldly mix of metal and rock.

This composition is a life-or-death matter for the rock. A fragile, porous, stony meteoroid might completely disintegrate in the atmosphere. But a dense, solid iron meteoroid? It has a much better chance of surviving the plunge.

Then What Am I Really Seeing During a “Shooting Star”?

This is my favorite part of the story, because what you think you’re seeing isn’t what’s happening at all.

When you see that streak of light—the meteor—it’s natural to assume you’re watching the rock itself burning up, like a log in a fire.

Nope.

It’s not fire. It’s plasma.

Is the rock itself on fire?

No. There’s no combustion happening, which is what fire is. In fact, the rock is so high up (typically 50-70 miles) that there’s barely any oxygen to burn anyway.

What you are really seeing is the air.

A meteoroid slams into our atmosphere at insane speeds. It could be 25,000 miles per hour, or it could be over 160,000. At that velocity, it doesn’t just “push” the air aside. It compresses the air in front of it so violently and so rapidly that the air itself heats up to thousands of degrees. This process is called “ram pressure.”

The air in the meteoroid’s path is superheated into a glowing, incandescent tube of plasma. That’s the streak you see.

The rock itself is definitely getting hot. It’s melting and vaporizing from this heat, a process called ablation. But the brilliant light? That’s the air. The rock is the bullet; the glowing plasma trail is the tracer.

What about “Fireballs” and “Bolides”?

Sometimes, you see a meteor that makes you gasp. It’s not a faint, quick streak. It’s a massive, brilliant flash that lights up the entire sky, casts shadows on the ground, and can last for several, unforgettable seconds.

These have special names.

A fireball is the term for any meteor that is exceptionally bright—specifically, brighter than the planet Venus (which is usually the brightest object in the sky after the Sun and Moon). These are caused by meteoroids that are a bit larger, maybe the size of a pebble or a baseball.

A bolide is a fireball that takes it one step further: it explodes. As the meteoroid plumms deeper, the air pressure can become so great that the rock shatters in a terminal burst, releasing all its kinetic energy at once. This is often accompanied by a sonic boom that can be heard (and even felt) on the ground minutes later. The famous 2013 Chelyabinsk event in Russia was a bolide. It was caused by an “asteroid” (because it was ~60 feet across) and its shockwave shattered windows for miles.

Why do some meteors look green or red?

You’re not imagining it! Meteors absolutely have colors, and those colors are a beautiful bit of high-speed chemistry. The color comes from two sources: the gasses in our atmosphere getting “excited,” and the elements inside the meteoroid itself as it vaporizes.

- Green: This is the most common color you’ll see in bright meteors. This is the signature glow of oxygen atoms in our upper atmosphere, about 60 miles up, getting energized by the meteor’s passage.

- Orange/Red: This is often the glow of nitrogen atoms in the air, a little lower down.

- Yellow: A persistent yellow streak often points to iron atoms from the meteoroid itself.

- Purple/Violet: This can indicate calcium inside the rock.

- Blue-Green: This can be a sign of magnesium or even copper.

So when you see a bright green fireball, you are literally watching the rock’s energy electrify the oxygen in our planet’s air.

What’s the deal with meteor showers like the Perseids?

This brings us right back to the comets. Remember how comets are “dirty snowballs” that leave a trail of debris along their orbit?

Well, Earth’s own orbit around the Sun is a fixed path. And several times a year, our planet’s path takes us directly through one of these ancient, dusty comet trails.

The result is a meteor shower.

Instead of just one or two random (“sporadic”) meteors an hour, our planet plows into this dense stream of debris. We’re suddenly hit by hundreds or thousands of these tiny meteoroids, most no bigger than a grain of sand. They all slam into our atmosphere at once, creating a spectacular, hours-long light show.

We name these showers after the constellation they appear to be coming from in the sky. This point is called the “radiant.”

- The Perseids in August appear to radiate from the constellation Perseus. (This is the debris trail of Comet Swift-Tuttle).

- The Leonids in November seem to come from Leo. (Debris from Comet Tempel-Tuttle).

- The Geminids in December look like they’re coming from Gemini. (This one is an outlier, as its parent is an asteroid named 3200 Phaethon).

This “radiant” is purely an effect of perspective. It’s the exact same as driving your car into a snowstorm and seeing all the snowflakes appear to come from a single point in the distance, right in front of you.

And What Happens When One Actually Survives the Trip?

Most meteoroids are tiny. They completely vaporize in the atmosphere, ending their long journey as a brief, beautiful meteor.

But the bigger ones? The tougher, denser, iron-rich ones? They have a chance.

When any solid piece of that object survives the terrifying, fiery plunge and physically lands on Earth’s surface, its name changes for the last time. It becomes a meteorite.

This is the holy grail. It’s the one part of the process you can actually hold in your hand.

How much of the original rock makes it to Earth?

Shockingly little. The atmospheric journey is brutal. The process of ablation strips away 90%, 95%, or even 99% of the object’s original mass. A rock the size of a small car might only produce a few pieces the size of a basketball, or a scattering of fist-sized fragments.

And here’s another myth to bust: meteorites are not glowing red-hot when they land.

The “fireball” stage, the part where it’s screaming-hot, happens 50 or 60 miles up in the atmosphere. For the last several miles of its journey, the rock is no longer moving at hypersonic speed. It’s been slowed down by the thick lower atmosphere and is just falling at terminal velocity (which is still fast, maybe 200-400 mph, but not fast enough to glow).

By the time it hits the ground, the intense cold of the upper atmosphere has already cooled it. Meteorites are almost always found cold, or at worst, warm to the touch. The one tell-tale sign of its journey is a “fusion crust”—a thin, dark, glassy, or “eggy” coating that formed when the very outer layer of the rock melted during its plunge.

If they’re all over, why don’t I have one in my backyard?

They are rarer than you’d think, but also more common than you’d imagine. Scientists estimate that thousands of meteorites hit the Earth every single year.

So why aren’t we all tripping over them?

Well, first, 70% of our planet is covered in water. The vast majority of meteorites are lost forever at the bottom of the ocean.

Of the 30% that hit land, many are never found. They land in remote jungles, dense forests, or on inaccessible mountains. And on most of the planet, Earth’s weather is a meteorite’s worst enemy. Rain and oxygen cause the iron in them to rust and disintegrate. They break down, and within a few years or decades, they just look like any other rusty old Earth rock.

This is precisely why scientists go to two specific places to hunt for them: deserts and Antarctica.

It’s not because more meteorites fall there. It’s because they are easier to see and better preserved. A dark, charred rock sticks out like a sore thumb against a vast, white ice sheet or a flat, sandy desert. Even better, the cold, dry (desert) conditions in these places protect the meteorites from rust and decay for thousands, or even tens of thousands, of years.

Why do scientists get so excited about these space rocks?

Why all the fuss? Why do people dedicate their lives to braving Antarctic winds to find a small, dark rock?

Because a meteorite is a time capsule.

It is a pristine, physical piece of our solar system, unchanged for 4.6 billion years. The rocks on Earth have all been melted, weathered, and recycled through volcanoes and plate tectonics. They’re all “new” rocks. But a meteorite is a direct sample of the raw ingredients that built the planets, including our own. It’s a fossil from before the planets even existed.

When scientists study a meteorite, they are looking at the building blocks of our solar system. Some meteorites, like the famous Murchison meteorite that fell in Australia in 1969, are a special type called carbonaceous chondrites. They are special because they contain water and complex organic compounds—including amino acids.

That’s right. The literal building blocks of life.

These rocks from space are carrying profound clues about our own origins, and the origins of life on Earth.

What About All Those Other Space Words?

Okay, so we’ve nailed the big three: meteoroid, meteor, meteorite. You’re feeling confident. But then someone throws out “asteroid” or “comet.” How do they fit into the puzzle? We’ve touched on this, but let’s make it crystal clear.

Asteroid vs. Meteoroid: Isn’t it just about size?

Yep. That’s it. That’s the only difference. Both are chunks of rock and/or metal orbiting the sun. It’s a simple, human-made size classification.

- Asteroid: The big ones (anything larger than 1 meter / 3.3 feet across).

- Meteoroid: The little ones (anything smaller than 1 meter).

An asteroid can create meteoroids when it breaks up. And as we discussed, if a 50-foot rock is on a collision course with Earth, astronomers will call it an “asteroid” right up until the moment it hits the atmosphere. Then, the light it produces is a “bolide” (a type of meteor), and the pieces that land are “meteorites.”

The line is blurry, but “asteroid” implies a significant object that we track, while “meteoroid” implies a smaller piece of debris.

Okay, so what’s a Comet, then?

This one is different. It’s not about size; it’s about composition.

Asteroids and meteoroids are primarily rock and metal. Comets are primarily ice, dust, and rock.

This is why comets are often called “dirty snowballs.” They come from the outer, frozen reaches of the solar system. While asteroids are just dark, rocky bodies, comets change when they get near the sun. The heat vaporizes their ices (a process called sublimation), creating a glowing “coma” (or atmosphere) and one or more spectacular tails of gas and dust that can stretch for millions of miles.

The key connection is this: Comets shed trails of meteoroids, which are what create our most spectacular meteor showers.

Should I Be Worried About This Stuff?

It’s a valid question. We’ve been talking about rocks from space hitting our planet at hypersonic speeds. It sounds, and is, incredibly violent.

The short answer is: no. The long answer is: it’s complicated, but for the first time in human history, we’re actually learning how to do something about it.

Do big ones ever hit us?

Yes. All the time. But “big” is relative.

- Sand-sized meteoroids hit our atmosphere constantly. These are the gentle, pretty “shooting stars.” You’re safe.

- Pebble-sized meteoroids create bright fireballs a few times a night, all over the globe. You’re safe.

- Car-sized meteoroids enter the atmosphere several times a year, creating spectacular bolides that usually explode harmlessly high above the ocean (like Chelyabinsk, which was an exception that caused damage). You’re safe.

- Football-field-sized asteroids hit every few thousand years and can cause major regional damage (like the 1908 Tunguska event in Siberia).

- Civilization-ending asteroids (miles wide, like the one that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago) are exceptionally rare, hitting on scales of tens of millions of years.

So, while the planet is constantly being hit, the risk to you, personally, is practically zero. You have a better chance of being hit by lightning.

What is NASA doing to protect us?

Scientists at NASA and other space agencies around the world take this risk, however small, very seriously. It’s the only natural disaster we can potentially predict decades in advance and actually prevent.

They run sophisticated programs like the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) to scan the skies, night after night, for “Near-Earth Objects” (NEOs).

They are tracking thousands of asteroids whose orbits bring them close to Earth. The good news? They’ve cataloged over 90% of the truly giant, planet-killer-sized ones, and happily, none are on a collision course for the foreseeable future.

The focus now is on finding all the smaller, “city-killer” sized ones (in the 140-meter range and up).

And they’re not just watching. They’re learning to act. You may have heard of the DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) mission. In 2022, NASA intentionally slammed a vending-machine-sized spacecraft into a small asteroid named Dimorphos, millions of miles from Earth.

The goal wasn’t to destroy it. It was to see if we could nudge it. To see if a “kinetic impact” could change an asteroid’s orbit.

And it worked. It worked better than anyone expected.

We now have hard proof that if we find a dangerous asteroid decades in advance, we have the basic technology to give it a little push, changing its path just enough so that, years later, it misses Earth completely.

So, the next time you’re out under the stars and you see that breathtaking flash of light, you’ll know the whole story.

You’ll know you’re not just seeing a “shooting star.”

You’re seeing a meteor. You’re watching the dramatic, fiery end of a meteoroid—a tiny, ancient piece of an asteroid or a comet—as it concludes its four-and-a-half-billion-year journey. And you’ll know that somewhere, in a quiet desert or a frozen wasteland, a scientist might one day find the meteorite it left behind: a priceless gift from the stars, a time capsule that helps us understand where we all came from.

FAQ – Difference Between Meteoroid Meteor Meteorite

How do the terms meteoroid, meteor, and meteorite relate to each other?

They describe the same object at different points in its journey: in space (meteoroid), burning in the atmosphere (meteor), and after reaching the ground (meteorite). The names change based on location, not the object.

What size determines if a space rock is called a meteoroid or an asteroid?

The classification is based on size: a meteoroid is any debris smaller than one meter across, while an asteroid is larger than one meter.

What causes the colors seen in meteors, like green or red flashes?

The colors in meteors are caused by elements in the meteoroid vaporizing and reacting with the Earth’s atmosphere, such as oxygen creating green, nitrogen creating orange or red, iron creating yellow, and calcium or copper creating violet or blue-green hues.

Are meteorites dangerous or worth worrying about?

Most meteorites are very small and pose no threat to humans, as larger impacts are extremely rare and scientists actively monitor near-Earth objects to prevent any potential collisions.