Look up on a clear, dark night. What do you see?

If you’re lucky enough to be away from the glare of city lights, you’ll see a black velvet dome sprayed with thousands of twinkling stars. It’s overwhelming. It’s beautiful.

And for as long as humans have looked up at that sprawl, we have done one, irresistible thing: we’ve connected the dots.

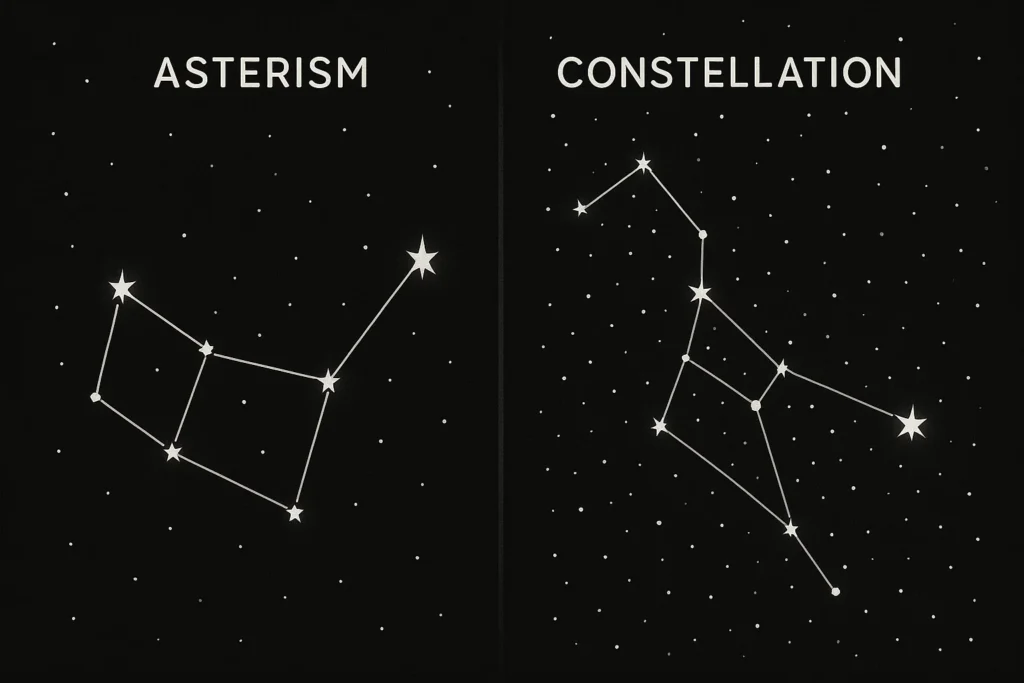

We see patterns. We see hunters, bears, queens, and teapots. It’s a universal human impulse, this need to find order in the chaos. But in this stellar connect-the-dots game, two words get tossed around as if they’re the same thing: “constellation” and “asterism.”

Most people use them interchangeably.

They are not. Not even close.

Understanding the difference between asterism and constellation is the first, and most important, “a-ha!” moment for any budding stargazer. Honestly, it’s the key that unlocks the entire map of the night sky. So, let’s clear up the confusion for good. This article will explain the precise difference and forever change how you look at the stars.

More in Celestial Objects Category

Difference Between Gas Giant and Star

Difference Between Ice Giant and Gas Giant

Key Takeaways

Before we dive deep, here’s the quick-and-dirty answer you need to know:

- Constellations are official borders. A constellation is one of 88 official regions of the sky. Think of it like a state or country on a map. These regions have precise boundaries and, all together, they cover the entire celestial sphere.

- Asterisms are unofficial pictures. An asterism is a recognizable, “unofficial” pattern or shape of stars. It’s a nickname. It’s the picture we see.

- Constellations are the “map.” The International Astronomical Union (IAU) designates these 88 regions so astronomers can pinpoint where things are. When they say a new comet is “in Leo,” they mean it lies within that specific region’s borders.

- Asterisms are the “landmarks.” The Big Dipper is the most famous example of an asterism. It’s an easy-to-spot shape, but it is not a constellation.

- An asterism can be part of a constellation. Here’s the key: The Big Dipper (the asterism) is actually just a small, famous part of the much larger Ursa Major (the constellation).

So, What Exactly Is a Constellation, Then?

This is where the confusion usually starts, and you’re not alone if you’re mixed up. When you hear “constellation,” you probably picture a stick-figure, like the hunter Orion with his belt and sword. That’s what I thought for years.

But that’s not the modern, official definition.

A constellation is an area.

That’s the big secret. Think of the entire night sky—the whole 360-degree sphere around our planet—as a giant, spherical map of the Earth. This map has been neatly divided into 88 “countries.” Each one of these 88 “countries” is a constellation.

There are no gaps. No overlaps. Every single star, galaxy, and nebula in the sky, no matter how bright or faint, falls within the borders of exactly one constellation.

It’s a celestial zoning map.

This official map was formally established by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) back in the 1920s. Why? Because science demands precision. Astronomers from Japan, Brazil, and Germany all needed a clear, unambiguous system to name and locate objects. They couldn’t just say a new comet was “sort of near the lion’s head.” They needed to be able to state, definitively, that it was “in” the constellation Leo.

So, when an astronomer says “Orion,” they aren’t just talking about the seven or eight bright stars that make up the hunter’s body. They are referring to the entire jagged-edged, 594-square-degree patch of sky that contains those stars, plus all the empty space and thousands of fainter stars within its official boundaries.

Wait, Constellations Are Regions? Not Pictures?

Exactly. This is the single most important concept to grasp. Once you get this, everything else clicks into place.

What about the stick-figure pictures we all associate with them?

Those are just memory aids. They’re a “connect-the-dots” game we play using only the brightest stars within that region to help us find it.

Let’s use an analogy. Think of the constellation Ursa Major (the Great Bear) as the entire U.S. state of Texas. It has specific, official borders on the map. An astronomer might find a supernova within the “state” of Ursa Major.

Now, think of a famous landmark inside Texas, like the city of Austin. Austin is not Texas. It’s just a well-known, easy-to-find part of Texas. You wouldn’t say you visited “all of Texas” just because you went to Austin, right?

In this analogy:

- Texas = The Constellation (Ursa Major)

- Austin = The Asterism (The Big Dipper)

The pictures we call “constellations” are just popular landmarks inside much larger, invisible territories.

Where Did These 88 Constellations Come From?

These official regions didn’t just appear out of thin air. They have a rich, long, and very human history. They’re a blend of ancient sky-lore and modern astronomy.

The foundation was laid thousands of years ago. Ancient civilizations—Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks—were meticulous stargazers. They weren’t just looking for gods; they were looking for clocks and calendars. The sky was their guide. The rising of a certain star pattern told them when to plant their crops, when the rivers would flood, and when to harvest. For sailors, the stars were the only map they had.

The Greek-Roman astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, in the 2nd century AD, cataloged 48 of these patterns in his famous work, the Almagest. These are what we now call the “ancient constellations,” and they include all the familiar names like Orion, Taurus, and the signs of the Zodiac. They are the mythological heart of our sky.

But Ptolemy lived in the Northern Hemisphere. He could only see the sky visible from Alexandria, Egypt. The entire southern sky was a complete blank on his map.

Fast-forward to the Age of Exploration.

From the 16th to 18th centuries, European navigators like Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman sailed south of the equator. They charted the strange, new stars of the Southern Hemisphere. Lacking the mythology of the Greeks, they named these new patterns after the tools and exotic creatures of their time: Tucana (the Toucan), Musca (the Fly), and Telescopium (the Telescope).

For a while, the map was a mess. Different astronomers drew different lines and “invented” their own constellations, leading to overlap and confusion.

Finally, in 1922, the newly-formed IAU stepped in to standardize everything. They officially adopted a list of 88 constellations. Then, in 1930, Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte drew the final, precise, non-overlapping borders for all 88, which are the boundaries we still use today. They kept the ancient, mythological names for the regions but made their borders scientific.

If That’s a Constellation, What Is an Asterism?

This is where it all comes together.

An asterism is simply a popular, recognizable pattern of stars. It’s a “nickname” for a star shape. It’s what we see.

The key word is unofficial.

Asterisms are the folk-songs of the sky. They aren’t on any official IAU map. They have no official borders. They are just shapes that people, for generations, have found helpful or beautiful. They are the “landmarks” we use to navigate the “countries” (constellations).

This is the very heart of the difference between asterism and constellation: official region vs. unofficial pattern.

Does “Unofficial” Mean Asterisms Aren’t Real or Important?

Absolutely not. In fact, you could argue they are more important for the average person just starting out.

Let’s be honest. Asterisms are often brighter, more obvious, and far easier to find than their host constellations. Nobody goes out to find the entire faint, sprawling, zig-zagging outline of Ursa Major.

They go out to find the Big Dipper.

Asterisms are the “training wheels” of astronomy. They are the on-ramps to the celestial highway. You use these simple, obvious patterns to “star hop” your way to fainter, more complex constellations and deep-sky objects. Without asterisms, the night sky would be a daunting, featureless mess.

Can You Give Me the Most Famous Example?

I’ve been using it this whole time, and for good reason. The Big Dipper is the textbook example for understanding this entire concept.

You know it. You’ve seen it. You can probably sketch it from memory right now: four stars for the “bowl” and three for the “handle.”

Here’s the big reveal: The Big Dipper is not a constellation.

It is, without a doubt, the most famous asterism in the Northern Hemisphere.

So, What Constellation Is the Big Dipper In?

The Big Dipper is the brightest and most obvious part of the official constellation Ursa Major, which means “the Great Bear.”

The seven stars of the Dipper form the bear’s hindquarters and its unnaturally long tail. (Why a bear has a long tail is a whole other story). The full constellation of Ursa Major includes many other, fainter stars that form the bear’s head, legs, and paws. Most people have never seen the full bear. It’s big, dim, and doesn’t really look like a bear.

But the Dipper? It’s bright. It’s obvious. And it’s always there, circling the North Star.

This is the perfect illustration.

- Asterism: The Big Dipper (the 7-star “pan” shape).

- Constellation: Ursa Major (the entire, 889-square-degree region containing the Dipper).

Once you get this, you get everything.

What Are Some Other Types of Asterisms?

This is the fun part. Once you realize asterisms are “unofficial” patterns, you start seeing them everywhere. They generally fall into two categories.

1. Asterisms Within a Single Constellation

These are smaller, obvious patterns that are part of a larger, official constellation. Just like the Big Dipper.

- The Little Dipper: This is another classic. It’s an asterism within the constellation Ursa Minor (the Little Bear). The most famous star in this asterism is Polaris, the North Star, which sits at the very end of the handle.

- The Teapot: Look to the constellation Sagittarius (the Archer). Honestly, seeing an archer in those stars is… a stretch. But what’s incredibly easy to see? A teapot. It has a handle, a lid, and a spout from which the “steam” of the Milky Way galaxy billows out on a dark night.

- Orion’s Belt: Yes, even this is an asterism. The three bright stars in a perfect, short row (Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka) form a famous asterism within the constellation Orion (the Hunter).

- The Northern Cross: The constellation Cygnus (the Swan) is large. But its brightest stars form a perfect, large cross. This asterism is much easier to spot than the full swan, which it represents.

- The Sickle: The constellation Leo (the Lion) is marked by a backward question-mark shape that forms the lion’s head and mane. This dot-hook shape is a prominent asterism called “The Sickle.”

2. Asterisms Spanning Multiple Constellations

This is what really solidifies the difference. These are huge patterns made by “borrowing” the brightest stars from several different official constellations. They completely ignore the IAU’s borders.

- The Summer Triangle: This is the heavyweight champion of “cross-border” asterisms. It’s a massive, easily-seen triangle that dominates the summer sky. It’s made of three of the brightest stars available, each from a different “country”:

- Vega (in the constellation Lyra, the Lyre)

- Deneb (in the constellation Cygnus, the Swan)

- Altair (in the constellation Aquila, the Eagle) Each star is the “alpha” (brightest star) of its own constellation, but together they form an even more prominent asterism.

- The Winter Hexagon (or Winter Circle): This is another giant, composed of six brilliant stars from six different constellations. It’s less of a “picture” and more of a “tour” of the brightest winter constellations: Rigel (in Orion), Aldebaran (in Taurus), Capella (in Auriga), Pollux (in Gemini), Procyon (in Canis Minor), and Sirius (in Canis Major).

- The Great Square of Pegasus: This is a large, boxy shape that forms the body of the horse in the constellation Pegasus. But one of its corners, the star Alpheratz, was officially given to the neighboring constellation Andromeda. So this “square” is a cross-border asterism, too!

Do the Stars in a Constellation or Asterism Actually Know Each Other?

What a great question. It gets at the next big illusion of the night sky.

The answer is almost always no.

The patterns we see—the asterisms and the constellation figures—are a flat, 2D projection. They are a line-of-sight trick. We see the stars on a flat “dome,” but space is 3D. The stars in a single pattern are almost always at vastly different distances from us, and from each other. They just happen to line up from our specific vantage point on Earth.

Let’s go back to Orion’s Belt.

- Alnitak (the easternmost star) is about 1,260 light-years away.

- Alnilam (the middle star) is much farther, at about 2,000 light-years away.

- Mintaka (the westernmost star) is the “closest” of the three, at about 1,200 light-years away.

They look like neat, evenly-spaced neighbors, but Alnilam is hundreds of light-years deeper in space than the other two. They have absolutely no physical relationship to one another.

It’s even true for the Big Dipper. The stars in its “bowl” and “handle” are all over the place. The star at the end of the handle (Alkaid) is 104 light-years away, while the star at the other end of the bowl (Dubhe) is 123 light-years away.

If you could fly in a spaceship “sideways” to Orion or the Dipper, the pattern would completely dissolve into a random-looking jumble of disconnected stars. The “hunter” and the “dipper” only exist from our perspective.

So What’s a Star Cluster, Then?

Now you’re thinking like an astronomer. This is the exception to the rule.

A star cluster is a group of stars that are physically related. They are “real” families. They were born together from the same giant cloud of gas and dust, and they are gravitationally bound, moving through space as a group.

And here’s the fun part: a star cluster can also be an asterism!

The best example is the Pleiades, also known as the “Seven Sisters.” You can see it in the winter sky, near Taurus. It looks like a tiny, shimmering, diamond-crusted “dipper” shape.

- It’s an asterism because it’s a well-known, visible pattern.

- It’s an open star cluster because those 7 (and hundreds more) stars are all related, all about 440 light-years away, and all moving together.

- It’s located in the constellation of Taurus (the Bull).

See how all three terms work together? The Pleiades is an asterism (pattern) and a cluster (physical object) located within the constellation (official region) of Taurus.

How Can I Start Spotting Asterisms and Constellations Tonight?

You don’t need a fancy telescope. You just need your eyes, a dark-ish sky, and a little patience. The best way to learn is by “star hopping,” which means using an easy-to-find asterism as your guide.

Your best friend, in the Northern Hemisphere, is the Big Dipper.

- Find the Big Dipper. It’s high in the sky in spring and summer, and lower to the horizon in fall and winter. It’s big and bright.

- Find the North Star. Use the two stars on the outside of the Dipper’s bowl (Merak and Dubhe). They’re the “Pointers.” Imagine a line connecting them and extending it “up” out of the bowl. The first bright star you hit is Polaris, the North Star.

- Find Your First Constellation. You’re already there. Polaris is the last star in the handle of the Little Dipper (an asterism), which makes up the main part of the constellation Ursa Minor (the Little Bear). You just used one asterism to find another asterism and a constellation.

- Arc to Arcturus. Go back to the Big Dipper’s handle. Follow the “arc” of the handle away from the bowl. The next super-bright, orangey-looking star you’ll run into is Arcturus. You just “arced to Arcturus!”

- Spear on to Spica. From Arcturus, keep that same curving path going. The next bright star you’ll hit is the bluish-white Spica. You “spiked on to Spica!”

- Find Two More Constellations. You just found the brightest stars in two more official constellations. Arcturus is the alpha star of Boötes (the Herdsman), which looks like a big kite. Spica is the brightest star in Virgo (the Maiden).

You’ve just learned to navigate the sky. That’s all it is. Using easy patterns to find the official regions.

What Tools Do I Need?

You can start with nothing, but a few simple tools make it much more rewarding.

- Your Eyes: The best tool you have. The most important tip: let them “dark adapt” for at least 15-20 minutes. That means no looking at your phone!

- A Star Chart (or Planisphere): A simple, rotating “star wheel” that shows you what’s up in the sky on any given date and time. It’s the old-school, analog way. No batteries, no screen to ruin your night vision.

- A Phone App: A modern planisphere. Apps like Stellarium, Star Walk, or SkyView use your phone’s GPS and compass to show you exactly what you’re pointing at. They are fantastic for beginners. Just be sure to switch it to “red light mode.”

- A Red Flashlight: If you’re using a paper chart, use a flashlight covered in red cellophane. Red light doesn’t destroy your night vision the way white light does.

- Binoculars: A good pair of 7×50 or 10×50 binoculars are, in my opinion, the best first “telescope.” You’ll be floored. You can’t see Saturn’s rings, but you can see the moons of Jupiter, the smudge of the Andromeda Galaxy, the craters on the Moon, and the stunning, rich beauty of a star cluster like the Pleiades.

Why Does Understanding the Difference Even Matter?

This isn’t just a case of “gotcha” trivia. Knowing the difference between an asterism and a constellation is fundamentally about clarity and navigation.

It’s like knowing the difference between a “highway” and a “state.”

If you read in the news that “Comet NEOWISE is visible in Ursa Major,” you’ll now know that doesn’t mean it’s “next to the Big Dipper’s handle.” It means it’s somewhere within the official borders of the Ursa Major region. You’d still need to use the Big Dipper (the asterism/landmark) to help you find the comet’s specific location, but you understand the terminology.

Asterisms are the landmarks. Constellations are the territories.

You need the landmarks to find your way around the territories.

But it’s more than just technical. Knowing this connects you to the sky in a deeper way. You’re not just seeing random dots; you’re seeing the map and the landmarks. You’re participating in a human tradition that’s tens of thousands of years old. You’re looking at the same patterns Julius Caesar and Cleopatra saw, the same “landmarks” that guided sailors and inspired poets.

A Final Look at the Sky

So, the next time you’re under that starry sky, you’ll see it with new eyes.

You’ll spot that familiar “W” shape and think, “Ah, that’s the asterism called the ‘W’ of Cassiopeia.” And you’ll know that the constellation of Cassiopeia is the entire official region of the sky surrounding that ‘W’.

You’ll see the three-star belt and know it’s the asterism of Orion’s Belt, the most famous landmark for finding the mighty constellation of Orion.

And you’ll see your old friend, the Big Dipper. You’ll smile, knowing it’s the most famous asterism in the sky, a friendly guidepost that lives inside the grand, invisible constellation of Ursa Major.

The difference is simple. An asterism is a picture. A constellation is the frame and the wall space it hangs on.

The map is waiting. Now, go outside and look up.

FAQ – Difference Between Asterism and Constellation

What is the fundamental difference between a constellation and an asterism?

A constellation is an official region of the sky with precise borders, covering the entire celestial sphere, while an asterism is an unofficial pattern or shape of stars that we recognize as a picture or landmark within one or more constellations.

Are asterisms officially recognized by astronomical authorities?

No, asterisms are unofficial patterns of stars that are used as navigation landmarks, unlike constellations which are officially designated regions with defined boundaries by the International Astronomical Union.

Can an asterism be part of a constellation?

Yes, an asterism can be just a recognizable shape within a larger constellation, such as the Big Dipper being part of the constellation Ursa Major.

Why are asterisms important for amateur stargazers?

Asterisms serve as easy-to-find landmarks that help beginners navigate the night sky, acting as simple patterns or “training wheels” to locate more complex constellations and celestial objects.