Imagine you’re adrift on a vast, dark ocean. Miles from anywhere. In the distance, a light. It appears, disappears, and appears again, pulsing with a perfect, clockwork precision. You know exactly what it is. It’s a lighthouse, a spinning beacon of safety warning you of the shore.

Easy enough, right?

Now, let’s swap the ocean for the unimaginable blackness of deep space. The light isn’t a warning; it’s a cosmic mystery, a beacon flashing with a regularity so perfect you could set the world’s clocks by it. This is a pulsar. For decades, astronomers have stared at this metronome, baffled and amazed by its pulse.

But this celestial clock isn’t a heart. It’s not a light switching on and off. So, what causes a pulsar to flash?

The answer is one of the most elegant, extreme, and just plain awesome bits of physics in the entire universe. It’s a story of a star’s violent death, its impossibly dense corpse, and a cosmic accident of alignment.

It is, as the title says, the ultimate lighthouse.

More in Celestial Objects Category

Why Are Neutron Stars So Dense

Key Takeaways

Before we dive into the wild mechanics of it all, here are the absolute essentials you need to know about why pulsars flash:

- A Pulsar is a Neutron Star: The flash we see comes from a pulsar. And a pulsar is the super-dense, city-sized corpse of a massive star that died in a fiery explosion called a supernova.

- It’s a “Lighthouse,” Not a “Pulse”: This is the main trick. The pulsar doesn’t actually pulse. It emits constant, steady beams of energy. The “flash” we see is just that beam sweeping across our line of sight as the star spins, exactly like a lighthouse beam sweeping over a distant ship.

- Rotation is the Engine: The pulsar spins incredibly, insanely fast. We’re talking hundreds of times per second in some cases. This rapid rotation is the engine that powers the entire mechanism.

- Magnetic Fields Create the Beams: Pulsars have the most powerful magnetic fields in the known universe. These fields act like a cosmic funnel, grabbing particles and shooting them out in two tight beams from the star’s magnetic poles.

- Alignment is Everything: We only see a pulsar if Earth happens to be in the “danger zone”—the path of one of these sweeping beams. If the beams miss us, we don’t even know the pulsar is there.

Before We Get to the “Flash,” What Was a Pulsar in Its Past Life?

You can’t understand the pulsar—this bizarre, spinning zombie star—without first understanding what it used to be. You just can’t have this extreme object without an equally extreme origin story.

And that story always begins with a star.

But not a star like our Sun. No, our Sun is pretty average. A pulsar is the ghost of a true giant. We’re talking about stars that kick off their lives with at least eight, and sometimes as many as 20 or 30, times the mass of our own Sun. They are the heavyweights of the galaxy.

For most of their lives, these behemoths live in a state of stunningly violent, yet stable, balance. Deep in their core, the star’s crushing gravity—a force trying to smash it into a single point—is perfectly held at bay by the outward blast of nuclear fusion. The star spends millions of years furiously fusing hydrogen into helium, then helium into carbon, and so on, creating heavier and heavier elements in a furnace that makes our Sun look like a chilly fireplace.

But this can’t last forever.

How Does a Giant Star Die?

Every star is in a constant fight against gravity. And gravity is the undefeated, undisputed champion.

When a massive star finally builds up a core of iron, it hits a wall. A fatal one. You see, fusing all the elements up to iron releases energy. That’s what holds the star up. But fusing iron doesn’t release energy.

It consumes it.

The furnace in the core sputters and dies. In an instant, the outward pressure that held the star up for millions of years just… vanishes.

Gravity wins. And it wins catastrophically.

The star’s core, which is already incredibly dense, collapses in on itself. We’re not talking about a gentle settling. We’re talking about a collapse at nearly 25% the speed of light. In less than a second, a core the size of our entire planet Earth crushes down to the size of a city.

This collapse triggers an unimaginable rebound. The core becomes so dense that it “bounces.” It’s like slamming a tennis ball against a brick wall. This bounce creates a shockwave that slams into the star’s outer layers, which are still falling inward.

The result is the most powerful explosion the universe can cook up.

What Is a Supernova, Really?

We call this explosion a supernova. For a few weeks, this single dying star can outshine its entire home galaxy. It will blaze with the light of billions of suns.

This is the event that seeds the universe. It’s a creative act of destruction. The explosion blasts those heavy elements the star spent its life making—the iron in your blood, the calcium in your bones, the oxygen you’re breathing—out into space. This is the only way the universe gets the raw materials needed to build rocky planets and, eventually, people.

It’s beautiful.

But for our story, the important part isn’t the explosion. It’s the tiny, secret thing left behind. After the dust and gas of the supernova have cleared, what remains of that massive core is one of the strangest objects in all of creation.

A neutron star.

This is the engine of the pulsar.

So, What’s Left Behind After the Smoke Clears?

The object that remains is a masterpiece of extreme physics. Calling it “matter” almost feels wrong.

The core’s collapse was so violent, so complete, that it overcame the forces that keep normal atoms apart. The electrons and protons in the core’s atoms were literally squeezed together to form a substance made almost entirely of… neutrons.

You are reading this because of electrical signals in your brain, moving between atoms that are 99.9% empty space. Imagine all that structure, all that space, gone. Crushed into a uniform, neutron-rich soup.

This “neutron star” is the pulsar. But calling it a “star” is almost misleading. It’s more like a single, planet-sized atomic nucleus, held together by gravity.

Just How Dense Is a Neutron Star?

Words like “dense” fail us here. They just don’t have the muscle.

A typical neutron star has more mass than our entire Sun. But all that mass is packed into a sphere no wider than Manhattan. Maybe 12 miles across.

Here’s the classic analogy, and it’s worth repeating because it’s so mind-bending: If you took a sugar-cube-sized amount of neutron star material, it would weigh about 100 million tons.

Let me say that again. A sugar cube. 100 million tons. That’s the weight of the entire human population, every man, woman, and child on Earth, packed into a space you could pinch between your fingers.

This density is the first key ingredient. The second is the spin.

How Fast Do These Things Spin?

Think about an ice skater. You’ve seen this. When a skater wants to spin faster, what do they do? They pull their arms in. This is a fundamental law of physics called the conservation of angular momentum. As a spinning object pulls its mass in closer to the center of rotation, the rotation speeds up.

Now, apply that to a star.

You have a massive star that rotates, maybe once every few weeks. Then, its core, which is thousands of miles wide, collapses into a ball just 12 miles across.

It’s like the ice skater pulling in their arms, magnified a trillion-fold.

The resulting neutron star spins at an almost unbelievable rate. A “young” pulsar can be born spinning dozens of times every second. Some spin hundreds of times per second. That’s a city-sized object, heavier than the Sun, rotating faster than a kitchen blender.

This spin is the pulsar’s power source. It’s the engine. But it’s not the beam. For that, we need the final, and most terrifying, ingredient: the magnetic field.

Okay, I’m Ready. What Causes a Pulsar to Flash?

We have our engine: a city-sized, super-dense, ridiculously fast-spinning ball of neutrons.

Just as the star’s spin was “conserved” and amplified, so was its magnetic field. Our Sun has a magnetic field. The Earth has one, and it’s strong enough to move a compass needle.

The magnetic field of a neutron star is… well, you get the idea. It’s extreme.

A pulsar’s magnetic field is trillions of times stronger than Earth’s. It is, quite simply, the strongest magnetic field we know of in the universe. It’s so strong it would warp the atoms in your body from a thousand miles away.

This monster magnetic field, coupled with the insane rotation, creates a dynamo effect. It generates a mind-bogglingly powerful electric field. This field is so strong it acts like a cosmic particle accelerator, ripping charged particles—electrons and their anti-matter cousins, positrons—right off the star’s crust.

These particles are then grabbed by the magnetic field and funneled. They are shot out from the star’s magnetic poles at nearly the speed of light.

What’s the “Lighthouse Beam” Actually Made Of?

Those particles, moving at relativistic speeds, are what create the “flash.” As they are accelerated along the curved magnetic field lines, they release a specific, intense kind of energy called “synchrotron radiation.”

This radiation creates two “searchlight” beams, one streaming from the magnetic north pole, one from the magnetic south pole.

These beams are the “light” of the lighthouse. For most pulsars, this beam isn’t visible light. It’s a powerful beam of radio waves. That’s why we “hear” pulsars with radio telescopes. The telescopes pick up the beam and translate the signal into a sound.

A rhythmic thump… thump… thump…

The Key Twist: Why Is the Magnetic Field So Important?

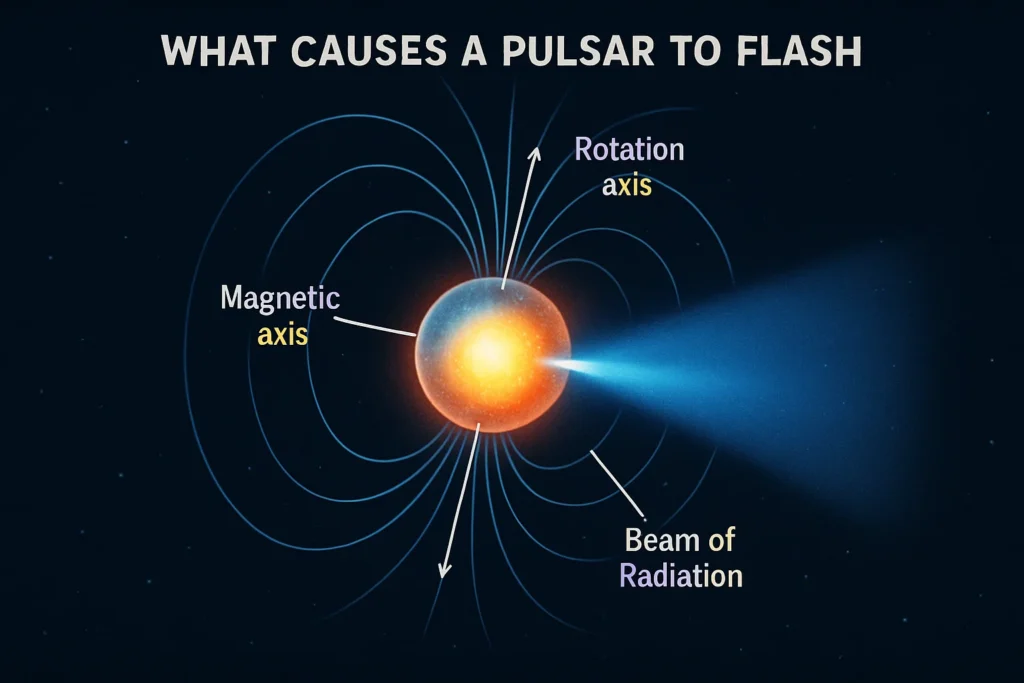

In a simple object, like a toy top or a perfectly balanced planet, the rotational axis (the pole-to-pole line it spins around) and the magnetic axis (the line connecting the magnetic north and south poles) are the same.

But in a complex, chaotic object like a neutron star, born from a violent explosion, they are not.

The spin axis—the imaginary rod the star spins around—is in one place.

But the magnetic axis—the line connecting the magnetic north and south poles where the beams are shooting from—is tilted.

It’s misaligned.

How Does That Misaligned Beam Create the “Lighthouse Effect”?

This misalignment is everything.

Because the magnetic axis is tilted, the beams are not pointing straight out from the “top” and “bottom” of the spinning star. They are tilted over.

Now, as the neutron star spins around its rotational axis, it drags that tilted magnetic field—and the beams—around with it.

The beams, fixed to the magnetic poles, are forced to sweep through space in a wide circle. They behave exactly, perfectly, like the light on a lighthouse, which is fixed to a rotating lamp.

The pulsar isn’t pulsing. It is shining constantly.

The star doesn’t care about us. It doesn’t know we exist. The beams are always on, sweeping the blackness of space, 24/7, for millions of years.

So, We Only See a “Flash” When the Beam Points at Earth?

You got it. We are a tiny, insignificant target in the vastness of space.

Most of the time, the pulsar’s beam is pointing somewhere else. We see nothing. We hear nothing. Then, for a fraction of a second, the pulsar’s rotation sweeps that powerful beam of radio waves across our planet.

Our radio telescopes get a blip.

The beam continues on its way, sweeping past us. Silence. Then, one rotation later—maybe a second, maybe a millisecond—the beam sweeps across us again. Blip.

The time between those blips? That’s the rotation period of the neutron star. If we get a pulse every 1.337 seconds, it’s because the star is spinning once every 1.337 seconds.

Does This Mean We’re Missing a Lot of Pulsars?

It means we’re missing most of them.

It’s just an accident of geometry. For every pulsar we can see, astronomers estimate there must be thousands more whose lighthouse beams simply don’t point in our direction.

Their beams are tilted in a way that, as they spin, they sweep out a circle of “empty” sky, never gracing our solar system.

They are out there, spinning and shining, but we are completely blind to them. We can only ever count the ones that happen to be pointing the right way.

Who First Discovered This Bizarre Cosmic Clock?

This discovery is one of the great stories in modern astronomy. And it wasn’t a famous, gray-haired professor who found it.

It was a graduate student.

In 1967, a young student from Northern Ireland named Jocelyn Bell Burnell was working at Cambridge University. She was helping to build a massive new radio telescope and, more importantly, she was in charge of analyzing its data. We’re not talking about digital files on a computer. We’re talking about miles and miles of paper from a chart recorder.

Her job was to sift through this mountain of paper, looking for the faint flicker of quasars. But she found something else.

Buried in the noise, she found a tiny, repeating signal. It was just a little “scruff” on the paper, as she called it. But it was persistent. It was fast. And it was pulsing with a regularity that was, frankly, impossible. It came every 1.337 seconds, on the dot.

What Was the “Little Green Men” Signal?

This signal was a huge problem. It was too fast to be a star. Normal stars don’t pulse in 1.3 seconds. It was too regular to be noise.

What in the universe could “pulse” with such metronomic precision? The team, led by her thesis supervisor Antony Hewish, half-jokingly nicknamed the signal “LGM-1.”

It stood for “Little Green Men.”

For a brief, tantalizing, and slightly terrifying moment, they had to seriously consider the possibility that they had discovered a signal from an alien civilization. An extraterrestrial beacon. It seemed more plausible than any natural explanation they had at the time.

How Did They Realize It Wasn’t Aliens?

The mystery deepened when Bell Burnell, refusing to dismiss the “scruff” as interference, went back through her endless piles of data. She found another one. Then another. And a fourth.

They were all pulsing with a similar, unnatural regularity, but they were coming from completely different parts of the sky.

This was the key. It was wildly unlikely that four separate, independent alien civilizations were all beaming signals at Earth in the exact same way.

This had to be a natural phenomenon. A new, unknown class of star.

The discovery, published in 1968, was dubbed a “pulsar” (for “pulsating radio star”). And it was the first confirmation that neutron stars, which had only been theoretical curiosities until then, were real. The “lighthouse effect” model fit the data perfectly.

Why Was Jocelyn Bell Burnell’s Discovery So Important (and Controversial)?

This discovery was revolutionary. It opened a brand new field of astronomy.

In 1974, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded for the discovery of pulsars. But it wasn’t given to Jocelyn Bell Burnell.

It was given to her supervisor, Antony Hewish, and another astronomer, Martin Ryle. Bell Burnell, the graduate student who had actually found the signal, who had pinpointed it, and who had argued it was real, was left off.

This decision is, to this day, one of the most significant controversies in science. Many prominent astronomers protested, but the Nobel committee held its ground. Bell Burnell herself has been incredibly gracious about it, but the incident is now a classic case study of how women and junior scientists are often overlooked in major discoveries.

She did, however, win the $3 million Breakthrough Prize in 2018. She donated the entire prize to fund scholarships for women and minority students to study physics.

Are All Pulsars Just Identical Spinning Beacons?

The universe is never that simple. Once astronomers knew what to look for, they started finding pulsars everywhere. And they discovered a veritable “zoo” of different types. It turns out, pulsars have a life cycle, and they can get weird.

What’s the Deal with “Millisecond Pulsars”?

The first pulsars, like the one Jocelyn Bell found, were fast—spinning once or twice a second. But then, astronomers found pulsars spinning hundreds of times per second.

The current record-holder, PSR J1748-2446ad, rotates 716 times every second.

Think about that. An object more massive than the Sun, the size of a city, spinning at 24% the speed of light. Its equator is moving at over 43,000 miles per second.

These “millisecond pulsars” are not young. They are ancient, “recycled” pulsars. They’re like cosmic vampires.

- They start as a normal pulsar, slowing down over millions of years, almost ready to “die.”

- But, this pulsar is in a binary system (it has a companion star).

- As its companion star gets old, it expands into a red giant, and its outer layers of gas get close to the “dead” pulsar.

- The pulsar’s immense gravity pulls this gas onto itself in a long, steady stream.

- This stream of falling matter, like a continuous, powerful jet pushing on a pinwheel, spins the old pulsar up, faster and faster, “recycling” it. It’s reborn as a millisecond pulsar, the fastest-spinning object in the universe.

What If the Magnetic Field Is Even Crazier?

We also found the inverse: pulsars that spin very slowly, but have magnetic fields that are a thousand times stronger than a normal pulsar’s (which was already trillions of times stronger than Earth’s).

These are the “magnetars.”

In a magnetar, the magnetic field is so powerful it dominates everything. It’s so strong it physically buckles and warps the star’s crust, causing “starquakes.” These quakes are so violent they release blasts of gamma rays and X-rays that can travel across the galaxy.

On December 27, 2004, a blast from a magnetar 50,000 light-years away hit our solar system. The blast was so powerful it physically compressed Earth’s own magnetic field. It was the brightest event ever seen on Earth from beyond our solar system, and it came from an object we couldn’t even see.

Why Should We Care About These Distant Lighthouses?

This is all fascinating, but you might be wondering, so what? They’re weird, fast-spinning lighthouses. Why do they matter?

It turns out pulsars are one of the most useful tools we have for understanding the universe. They are, quite literally, cosmic laboratories for testing physics we can never, ever replicate on Earth.

Can Pulsars Help Us Test Einstein’s Theories?

They already have. In 1974, astronomers Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor Jr. found a pulsar that was orbiting another neutron star. It was a binary pulsar system.

This was the perfect laboratory to test Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Einstein’s equations predicted that these two massive objects, orbiting each other so closely and moving so fast, should be radiating energy away in the form of “gravitational waves”—ripples in the very fabric of space-time itself.

As they lose that energy, their orbit should shrink. They should slowly, but measurably, spiral in toward each other.

Hulse and Taylor watched the system for years. And they found that the orbit was shrinking exactly as Einstein’s theory predicted, down to the decimal point. It was the first indirect (but overwhelming) proof that gravitational waves are real. It won them the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physics.

How Are Pulsars Being Used to Hunt for Gravitational Waves?

That legacy continues today, but on a galactic scale. Millisecond pulsars are the most stable “clocks” in the known universe. They are more precise than our best atomic clocks on Earth.

Astronomers are using this. Projects like the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav) are using dozens of these millisecond pulsars, scattered all across the sky, to create a galaxy-sized gravitational wave detector.

Here’s the mind-blowing idea:

- Scientists monitor the precise “tick… tick… tick” of all these pulsars.

- If a long, slow gravitational wave (the kind made by supermassive black holes merging) washes across our galaxy, it will stretch and compress space-time itself.

- This stretching and squeezing of space will cause the “ticks” from some pulsars to arrive a tiny bit early, and others to arrive a tiny bit late, all in a very specific, correlated pattern.

- In 2023, after 15 years of meticulous data collection, the NANOGrav collaboration announced they had found strong evidence for this very “background hum” of gravitational waves, opening a brand new window on the universe.

Do Pulsars Spin and Flash Forever?

This story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. A pulsar cannot spin and flash forever.

The lighthouse is powered by the rotation. The rotation is what generates the beams. But the beams themselves are a form of light, and light carries energy.

This means that by shining, the pulsar is radiating away its own rotational energy. It’s a “braking” mechanism.

Every flash, every single pulse, slows the pulsar’s spin down by an infinitesimal, but measurable, amount. It’s a tiny, tiny loss, but over thousands and millions of years, it adds up.

What Is the “Pulsar Death Line”?

A young, fast pulsar will slowly, inexorably, spin down. After 10 to 100 million years, the pulsar’s spin will become too slow. Its rotation won’t be fast enough to power the magnetic dynamo that generates the particle beams.

The electric field weakens. The particle acceleration stops. The beams fade and die.

The pulsar crosses what astronomers grimly call the “pulsar death line.”

The lighthouse goes dark.

It’s now just a cold, dark neutron star, still heavier than the Sun, still the size of a city, but no longer flashing. It’s a ghost, silently tumbling through the galactic graveyard, its story over…

…unless, of course, a billion years from now, it drifts into the orbit of a new, young star, and the cycle of “recycling” begins all over again.

The Cosmic Lighthouse, Still on Duty

It’s not a message. It’s not a heartbeat. It’s the unwavering, mechanical, cosmic accident of geometry and physics.

It is the echo of a star’s violent death, a monument to gravity’s ultimate victory. It’s an object so dense it defies intuition, spinning so fast it defies belief. And it’s a beacon, a lighthouse, whose sweeping beam of energy, born from a magnetic field of unimaginable power, just happens to cross our path.

With every flash, it tells us a story. A story about the death of stars, the nature of matter, and the very fabric of space and time.

We just have to be listening.

FAQ – What Causes a Pulsar to Flash

How is a pulsar related to its violent stellar death?

A pulsar is the dense remnant of a massive star that exploded in a supernova; its core collapses into a neutron star that spins rapidly and produces the pulsar’s distinctive beams.

Why is the magnetic axis of a pulsar tilted relative to its spin axis?

The magnetic axis is tilted because the neutron star’s formation process is complex and chaotic, causing the magnetic poles to not align with the rotational axis, which results in the sweeping beams.

What distinguishes a millisecond pulsar from regular pulsars?

A millisecond pulsar is a neutron star that spins hundreds of times per second, much faster than typical pulsars, and is generally older due to its evolutionary history.