When I was a kid, the answer to “how many moons in our solar system” was a party trick. Easy. You’d tick them off on your fingers. Earth has one. Mars, two. Jupiter had its four big ones. Saturn had a few. The whole solar system felt… tidy. Knowable.

Yeah, that solar system is long gone.

The real number is just staggering. And it seems to break its own record every few months. The “over 200” in my title? That’s already old news. The true count is rocketing past 300, maybe even 400. Our solar system, it turns out, is a chaotic, crowded, beautiful mess. We’re only just starting to get a full picture.

So, let’s go on a tour. We’ll count the confirmed, the new, and the just plain weird.

More in Fundamental Concepts Category

Difference Between Dwarf Planet and Planet

Key Takeaways

- Forget any static number. The total count is climbing, fast. In early 2024, the “confirmed” list was hovering near 300. Since then, new finds have pushed the known total well over 400.

- Saturn is the undisputed “moon king.” No contest. Astronomers recently confirmed over 120 new moons, pushing its total to a mind-boggling 274.

- The gas giants—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—are the hoarders. Their massive gravity snags the vast majority of these moons.

- The inner planets? Barren. Mercury and Venus have zero moons.

- Even tiny, distant dwarf planets like Pluto have their own families of moons, which messes with our old-school ideas of what a “system” should even look like.

What Exactly Is a “Moon,” Anyway?

This seems like it should be the easy part. It’s not.

We all know what a moon is. It’s… a thing. A thing that orbits a planet. Right? Well, mostly. A moon is, simply, a natural satellite. It’s a chunk of rock or ice that orbits a planet, a dwarf planet, or even a big asteroid.

But that’s where the simplicity ends.

The International Astronomical Union (IAU)—the folks in charge of naming things in space—have a super-strict, multi-part definition for a “planet.” (Just ask Pluto).

But for moons? Nothing. There is no official, IAU-sanctioned definition. No minimum size. No “you must be this round to ride” sign.

This creates a wonderfully fuzzy line.

Think about it. Is a boulder-sized piece of ice orbiting Saturn, one that’s a half-mile wide, a “moon”? What about a car-sized chunk? We call some of these tiny objects “moonlets,” especially the ones that hide inside Saturn’s rings. But when does a “moonlet” graduate to a “moon”?

It’s a judgment call.

For the most part, if it’s a natural object, it has a stable (or semi-stable) orbit around a larger, non-Sun body, and it’s big enough for us to find and track… we call it a moon.

So, What’s the Official Tally? (And Why Is It Already Wrong?)

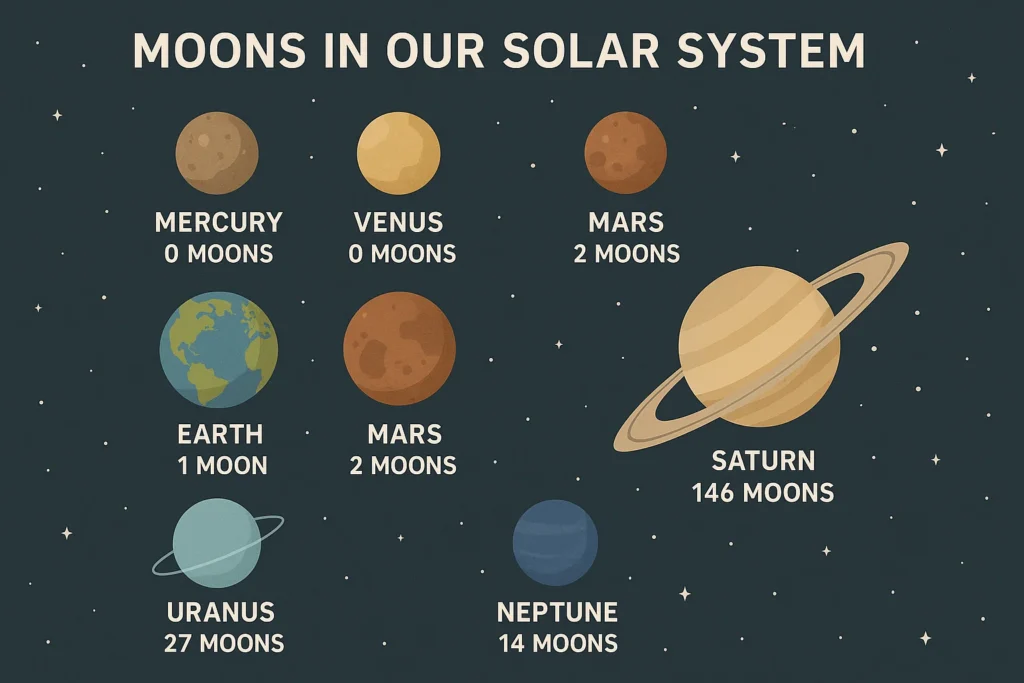

If you’d cornered a planetary scientist in February 2024, they’d have given you a number around 299. One for Earth, two for Mars, 95 for Jupiter, 146 for Saturn, 29 for Uranus, 16 for Neptune, and a handful for the dwarf planets.

That’s a respectable number.

But that number is a snapshot. It’s a picture taken in the middle of a race. The scenery is changing while the shutter is still open.

The real story, the one that makes this topic so exciting, isn’t the number itself. It’s the rate of discovery. That 299 number? It was shattered just a few months later. The tally I gave for Saturn (146) was completely and totally blown out of the water.

The solar system isn’t static. It’s not a museum piece. We are actively discovering it. Right now.

The Great Moon Race: Why Do Saturn and Jupiter Have So Many?

Let’s get this out of the way. The inner solar system is a ghost town for moons. The outer solar system is where the party is.

The reason is one word: gravity.

Jupiter and Saturn are monsters. They are so colossally massive that their gravitational pull dominates the outer solar system. They’re like cosmic vacuum cleaners. They suck in stray asteroids and comets that wander too close. Many of these objects are just flung out of the solar system entirely.

But some get trapped.

They’re captured. Snatched by that immense gravity, their trajectories are bent into an orbit. These become “irregular” moons. They often have strange, tilted, and very distant orbits. They’re the solar system’s hitchhikers.

For years, Jupiter and Saturn traded the “moon king” crown. For a while, Jupiter was in the lead. Then, in 2019, Saturn surged ahead. Then Jupiter found a few more. It was a friendly, cosmic rivalry.

And then, in 2024, Saturn ended the race.

Saturn Just Changed the Game, Didn’t It?

Yes. It absolutely did. The recent discoveries around Saturn aren’t just a small update. They’re game-changing. They’ve almost doubled the known moon count for the entire solar system all by themselves.

What’s the New Count for the Ringed Planet?

Remember that “official” count of 146? Forget it.

Starting in late 2024 and confirmed into 2025, astronomers announced the discovery of 128 new moons orbiting Saturn. That wasn’t a typo. One hundred and twenty-eight.

This instantly pushed Saturn’s total to an unbelievable 274 moons.

Two hundred. Seventy-four.

This one planet has more moons than we thought the entire solar system had for most of my life. These new discoveries are mostly small, irregular moons. They’re just a few miles across, dark, and incredibly far from the planet. They’re almost impossible to find. But as our technology gets better, we’re finding them.

Saturn’s lead is now so vast that Jupiter is a distant, distant second.

Is Saturn Hiding More Than Just Moons?

The crazy thing is, these hundreds of tiny, irregular moons aren’t even the main event. Saturn’s system is home to some of the most fascinating worlds in the solar system.

Its largest moon, Titan, is a planet in its own right. It’s larger than Mercury. It has a thick, smoggy, nitrogen-rich atmosphere. You couldn’t breathe it, but you could attach wings and fly in it. Under that smog, it has liquid methane rivers, lakes, and seas. It rains methane. It’s a bizarro, cryogenic version of Earth.

Then there’s Enceladus. This little moon is a snowball. It’s covered in bright, white ice. But under that ice? A global, liquid water ocean. And that ocean is active. Enceladus continuously spews gigantic geysers of salty water, ice, and organic molecules out into space from “tiger stripe” cracks at its south pole.

It is, without a doubt, one of the most promising places to look for life beyond Earth.

What About the Rest of the Solar System?

Okay, Saturn is the overachiever. But what about everyone else?

Why Are Mercury and Venus So Lonely?

Zero. Zip. Nada.

Mercury and Venus have no moons. Not one.

Why? They’re just too close to the Sun. The Sun’s gravity is the bully in this neighborhood. Any moon that tried to orbit Mercury or Venus would have its orbit destabilized by the Sun’s immense pull. It would either be ripped away and captured by the Sun or sent crashing into the planet.

It’s simply not a stable place to be a moon.

What’s Going On with Earth and Mars?

Earth has one. Our Moon. And we shouldn’t be so casual about it. Our Moon is weird. Most moons are tiny compared to their planet. Our Moon is over a quarter the diameter of Earth. It’s huge.

This size difference is the key clue to its origin. Scientists believe a Mars-sized planet (which we call Theia) slammed into the young Earth over 4 billion years ago. The debris from that cataclysmic impact eventually coalesced in orbit to form the Moon. It’s not a captured object; it’s a piece of Earth itself, blasted into space.

Mars has two tiny moons: Phobos and Deimos. They are not grand, spherical worlds like our Moon. They’re tiny. Phobos is only about 17 miles across. They look less like moons and more like lumpy, captured asteroids.

And Phobos is doomed. It’s orbiting Mars so closely that the planet’s gravity is tearing it apart. In a few tens of millions of years, Phobos will either crash into Mars or be shredded into a brand-new ring.

The Other Giants: What’s in Their Orbit?

Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune might not be Saturn, but they are still lords of their own domains, each with a fascinating and diverse family.

Jupiter: The “Classic” King with a Massive Family

Jupiter, with 95 confirmed moons, is no slouch. Its system is a mini solar system. While most of its moons are small, captured asteroids, four of them are legendary.

They are the Galilean moons. Galileo Galilei first spotted them in 1610. Their discovery was historic; it was the first proof that objects orbited a body other than Earth.

- Io: The innermost Galilean moon. It is a volcanic hellscape. Squeezed and stretched by Jupiter’s immense gravity, its insides are molten, and it erupts constantly through over 400 active volcanoes. It’s the most volcanically active body in the solar system.

- Europa: The most exciting moon. It’s a smooth, cue-ball-like world covered in a shell of water ice. Beneath this ice, we are almost certain there is a vast, global ocean of liquid, salty water—an ocean that may contain more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined.

- Ganymede: The king of all moons. Ganymede is the largest moon in our solar system, larger than the planet Mercury. It’s the only moon known to have its own magnetic field, which is a sign of a dynamic, liquid-iron core.

- Callisto: The most heavily cratered object in the solar system. Its ancient, pockmarked surface tells us that it’s been geologically “dead” for billions of years, a perfect record of the early solar system’s history.

Uranus and Neptune: The Icy, Distant Systems

Uranus has 29 known moons. In keeping with the planet’s weird, tilted-on-its-side nature, its moons are named for characters from the works of William Shakespeare and Alexander Pope. Its largest moons—Titania, Oberon, Umbriel, Ariel, and Miranda—are dark, icy worlds. A tiny new moon, S/2023 U1, was just confirmed in 2024, proving there are still discoveries to be made, even in old data.

Neptune has 16 known moons. Two of those were just confirmed in 2024, recovered from observations made years ago. But Neptune’s story is dominated by one moon: Triton.

Triton is a monster. It’s the seventh-largest moon in the solar system, and it’s likely a captured dwarf planet from the Kuiper Belt (the same region as Pluto). We know this because its orbit is retrograde—it orbits Neptune backward, against the planet’s rotation.

This is a cosmic death spiral. Triton is slowly spiraling inward and will one day be ripped apart by Neptune’s gravity, forming the most spectacular ring system the solar system has ever seen.

Are We Forgetting Someone? (Hint: The Dwarf Planets)

The main planets get all the attention, but the real revolution in our understanding of the solar system is happening in the deep dark. The dwarf planets, once thought to be lonely wanderers, have families.

Pluto’s Surprising Entourage

When the New Horizons probe flew by in 2015, it didn’t just find a dwarf planet. It found a complex, dynamic system.

Pluto isn’t alone. It has five moons.

- Charon: This is the big one. Charon is so large compared to Pluto (about half its size) that many scientists consider them a “binary system.” They don’t orbit each other; they both orbit a common point in space between them.

- Styx

- Nix

- Kerberos

- Hydra

These four smaller moons are tiny, icy, and orbit the Pluto-Charon system in a complex, chaotic dance.

Do Other Dwarfs Have Moons?

You bet. The discovery of these moons is often how we figure out the mass of these distant objects.

Eris, the dwarf planet that’s more massive than Pluto, has a moon named Dysnomia. Haumea, the weird, fast-spinning, football-shaped dwarf planet, has two moons: Hiʻiaka and Namaka. Makemake has one, nicknamed MK 2. And Gonggong has one, named Xiangliu.

Finding these moons proves that the outer solar system is littered with complex, multi-body systems.

How Are We Still Finding More?

So, how are we finding all these tiny, distant objects? Two ways.

First, our space probes. Missions like Cassini (at Saturn), Juno (at Jupiter), and New Horizons (at Pluto) gave us an up-close-and-personal look, finding tiny moons that are completely invisible from Earth.

Second, our ground-based telescopes have become ridiculously powerful. Astronomers now use a technique called “shift and stack.” They take hundreds of images of a patch of sky where a moon is predicted to be, but the moon is too faint to see in any single image.

Then, using computers, they shift all those images to follow the moon’s predicted path and “stack” them on top of each other. The background stars become streaks, but the faint, tiny moon builds up in brightness until it becomes a visible dot. It’s this painstaking, high-tech method that’s responsible for the recent explosion in moon discoveries at Saturn.

Why Do We Even Bother Counting?

This isn’t just cosmic stamp collecting. Every moon we find tells us a story.

The “regular” moons—the big ones in nice, circular orbits—tell us how the planets themselves formed from a swirling disk of gas and dust.

The “irregular” moons—the tiny, captured ones in weird orbits—are living fossils. They tell us a story of a much more violent, chaotic early solar system, a time when planets migrated and threw rocks around like a food fight.

And moons like Europa and Enceladus? They are a target. They are, quite possibly, the best chance we have of finding life. They are worlds, just as complex and fascinating as the planets they orbit.

The solar system has become infinitely more interesting. For more on the missions that discover these worlds, NASA’s Solar System Exploration page is a fantastic place to start.

It’s a wild place out there.

We started with a simple question: how many moons in our solar system? We found a simple answer: “we don’t know.” And that’s the best answer a scientist can give. It’s not a static number. It’s a scoreboard in a game we’re still playing.

The real number is well over 400 and climbing. Every new discovery proves that our solar system is more complex, more crowded, and more mysterious than we ever imagined. The next time you look up at our one, familiar Moon, just remember… it’s only one of a very, very large family.

FAQ – How Many Moons in Our Solar System

What is the current estimated number of moons in our solar system?

As of early 2024, the known total of moons in our solar system exceeds 400, with ongoing discoveries rapidly increasing this number.

Why do Saturn and Jupiter have so many moons compared to the inner planets?

Saturn and Jupiter have many moons because their massive gravitational pull captures stray objects like asteroids and comets, turning them into irregular moons that orbit these gas giants.

How do astronomers determine whether a body counts as a moon?

A body is generally considered a moon if it is a natural object that orbits a planet, dwarf planet, or large asteroid, and it is large enough to be detectable and have a stable orbit, though there is no official size limit.

What makes Saturn’s moon count particularly remarkable?

Saturn’s moon count is astonishing because recent discoveries have added 128 new moons, pushing its total to 274, making it the planet with the most moons in the solar system.

How do scientists find tiny, distant moons that are not visible from Earth?

Scientists use space probes for close-up observations and ground-based telescopes with techniques such as ‘shift and stack,’ which combine many faint images to reveal tiny, distant moons.